From the Chicago Reader (March 26, 1999). — J.R.

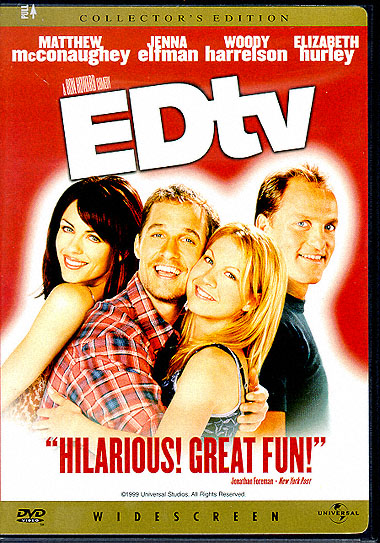

EDtv

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Ron Howard

Written by Lowell Ganz and Babaloo Mandel

With Matthew McConaughey, Jenna Elfman, Woody Harrelson, Sally Kirkland, Martin Landau, Ellen DeGeneres, Rob Reiner, Dennis Hopper, and Elizabeth Hurley.

I tend to like Ron Howard movies. They’re usually energetic, Capra-like popular entertainments that respect the audience — not a common virtue these days. Howard is one of the few remaining filmmakers from the Hollywood studio tradition who can be counted on to offer honest diversion without making any undue claims for what he’s doing — and I include everything from Grand Theft Auto and Night Shift to Splash and Cocoon, from Gung Ho and Parenthood to the underrated Far and Away, Backdraft, and The Paper, and even dubious efforts such as Willow and Apollo 13. Even when his films are satirical, as Gung Ho is, they don’t offer their commentaries from the top of soap boxes, and their messages are sweet tempered rather than caustic.

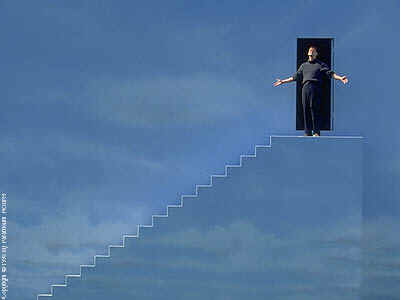

EDtv conforms to this pattern, though it runs up against a current conundrum — how can one criticize the excesses of the contemporary media without blaming the audience? The most common as well as the most dishonest solution for this problem is the one proposed by The Truman Show: to suggest simultaneously that the audience inside the movie is a pack of blithering idiots and that the audience outside the movie — the one watching The Truman Show — is a cultivated community of media-savvy individuals that knows what’s real and what’s bogus.

This snobbish double standard has become such an industry staple that we’re encouraged not to notice it, but to my mind it’s central to the various alibis for why studios and distributors offer us so few choices. We’re told, for instance, that we don’t see more subtitled movies because American audiences hate subtitles and that filmmakers can no longer shoot in black and white because American audiences hate black and white — which doesn’t explain why Dances With Wolves and Schindler’s List, both with subtitles and the latter in black and white, didn’t scare off anyone, nor does it account for the frequent use of black and white in music videos. In other words, audiences are always to blame, except when it’s not convenient to blame them. Rarely entertained is the possibility that the decision makers are narrow-minded simpletons who want to cover their own asses — who are interested only in short-term investments and armed mainly with that pseudoscience known as marketing research.

EDtv, which might be regarded in some ways as a populist reformulation of The Truman Show, offers us another 24-hours-a-day TV show devoted to one person’s life. But here the show unfolds in real locations rather than on a set, the person — a good-natured yahoo named Ed (Matthew McConaughey) who works in a video store — knows his life is being broadcast, and all this is happening in the present rather than in some hypothetical future. In “The Truman Show,” commercials are shoehorned into scripted dialogue delivered by actors to the unsuspecting Truman; in “EDtv,” they’re printed in a rectangular box that runs across the bottom of the TV image. Once again, the intrusiveness and vulgarity of the show are treated by the movie as excessive, though this time the mood is much more farcical and the target of the abuse isn’t the dim-wittedness of the audience but the exploitiveness and hypocrisy of the show’s producer (chiefly Rob Reiner; Ellen DeGeneres, who dreams up the show, is treated somewhat more sympathetically). But since the movie also suggests that these producers are right about what the public wants, condemning them for it is made to seem beside the point; it’s only their power to manipulate Ed and the audience that’s at issue.

Initially Ed goes along with the premise of having his life broadcast, both as a lark and because of the money being offered. Things start to get complicated early on when he inadvertently reveals that his brother Ray (Woody Harrelson), who wants to use the show to hype his own gym, is cheating on his girlfriend Shari (Jenna Elfman), a UPS driver. The story takes another turn once Ed and Shari get romantically involved. But as it becomes clear that Shari isn’t willing to pursue her love life in public, Ed arranges secret meetings, then has to confront the possibility that he may have to choose between her and his fast-growing celebrity. The manipulations of the show’s producers — they expose his mother’s sex life and produce another potential girlfriend to boost ratings — make his quandary even more acute.

It’s the secret meetings with Shari that pinpoint the movie’s contradictory attitude toward this raucous material (which is kept lively throughout by the flamboyant performances). On one hand, we see how the diverse responses of viewers — most of them couples — to “EDtv” fuel the grotesque intrusiveness and phony contrivances that quickly become part of the experience. On the other hand, no criticism is implied when the movie shows these viewers, unlike those in The Truman Show, as no more crass than anyone else in the picture. Theoretically, once we’re privy to Ed’s “secret” meetings with Shari we become implicated in the same voyeurism as the audiences. In effect, “EDtv” and EDtv become identical except for when we become more privileged than the viewers of the TV show and are thereby offered an “exclusive” denied to them. But the movie takes care not to rub our noses in the fact that our voyeurism overlaps with that of the TV show’s audience, even if we ultimately know more about what’s going on than they do. That the show itself is periodically made to seem ridiculous never threatens to make us feel silly for watching snatches of it ourselves; the overall carnivalesque tone of the proceedings is too generous and tolerant for that.

One might say that at this point Howard’s respect for his audience dovetails with what could be called his respect for his audience’s lack of seriousness. This effectively short-circuits any sustained satirical impulse the movie might have, and what we’re left with isn’t so much commentary as a playful enjoyment of absurd aspects of our TV culture.

Maybe this is because it’s become too difficult to criticize the media without becoming part of what one’s criticizing. Significantly, the same conundrum proposed by EDtv and The Truman Show is faced by most media commentary on the Monica Lewinsky overkill. Despite the Barbara Walters “exclusive,” it’s been periodically claimed that (a) much of the public doesn’t give a flying fuck about Monica Lewinsky, and (b) most of the media don’t give a flying fuck about changing their news coverage accordingly. Anyone who bothers to protest the overkill inevitably winds up becoming part of the Lewinsky babble– and insisting that we’re not doing the same thing as Geraldo Rivera isn’t much different from The Truman Show or EDtv insisting that they don’t include their own audiences in what they find questionable or ridiculous.

In other words, it’s a no-win situation, because the set of assumptions ruling telejournalism has us all trapped. We’re a captive audience in a sense, even if we turn off our TV sets. When I attended the funeral of Gene Siskel in Highland Park a few weeks ago, a crowd of camera people was stationed outside the synagogue shooting some of the visitors as they emerged. I had to suppress a strong urge to give them the finger. I thought what they were doing was in bad taste, but had I given them the finger and wound up on the evening news, my taste and not theirs would have been thrown into question. Back in the 60s and early 70s such a rude gesture might have registered more meaningfully, but that was because in those days television was more correctly viewed as only one version of what was going on and was counteracted by a communal grapevine. (EDtv also gives us two versions of what’s going on — the TV show itself and various “offscreen” events. But it also takes pains not to make these two versions seem unduly dialectical or contradictory, at least until the producer’s manipulative power has to be overcome in order to make way for a happy ending.)

Today, when the tabloid media are practically all we have and the New York Times and the National Enquirer register as sisters under the skin, we’re free to ignore them all — but only at the risk of being made to feel culturally irrelevant and apathetic about issues. And if we decide to watch the TV news or look at a newspaper, we become implicated in the same assumptions about the low tastes of the audience that gave rise to the Lewinsky overkill in the first place. In other words, we’ve been defined by market researchers as prurient assholes if we attend to the news and apathetic slugs if we ignore it.

Whether it wants to or not, a movie like EDtv has to grapple with this problem if it wants to make any sense of its ostensible subject. It’s to the credit of Howard and his screenwriters that by grappling with this paradox as unobtrusively, as noncommittally, and as inconclusively as possible, they avoid making us feel like either prurient assholes or apathetic slugs. But it’s also Howard’s and his audience’s misfortune that a good time can be had by all only if nothing of substance gets said.