Written for a collection edited by Adam Cook, Making the Case: Contemporary Genre Cinema, whose publisher belatedly changed his mind about publishing. This is the article’s first appearance, although it’s also reprinted in my latest book, Cinematic Encounters 2: Portraits and Polemics. — J. R.

Out of his half-dozen comedy features to date as producer-writer-director — Terms of Endearment (1983), Broadcast News (1987), I’ll Do Anything (1994), As Good as It Gets (1997), Spanglish (2004), and How Do You Know (2010) — James L. Brooks has had three big commercial successes (the first two and the fourth) and three absolute flops (the third, fifth, and sixth). And because all six of these movies are concerned equally with personal failure and personal success, functionality (emotional and professional) as well as dysfunctionality (emotional and professional), it somehow seems fitting that each one has represented a highly ambitious as well as a highly risky undertaking.

The above paragraph has the disadvantage of making Brooks seem so unexceptional as a commercial filmmaker that one might wonder, on the basis of this description, whether he’s worth examining at all. Some might also question whether all six of his movies qualify as comedies, despite Brooks’ own insistence that they do. Read more

My favorite online film magazine

I’m a frequent contributor to Rouge, so I hope nobody thinks I’m tooting my own horn if I come right out and say that I regard it as the best film magazine going that’s exclusively online. It’s been around since 2002, and it happens to be based in Australia, but you might not even notice this if you were scanning the table of contents of any issue, because it’s far and away the most international of film magazines in English. The latest issue, number ten, has contributors from Australia, Brazil, France, Hungary, Japan, Portugal, Russia, and the U.S., including some filmmakers (Pedro Costa and Mark Rappaport) as well as critics writing about films from most of those countries plus England, India, and Bosnia. About half of the 16 contributors are writing in English, about a third are translated from French, Japanese, or Portuguese, and a couple more express themselves exclusively in the form of a photograph or film frames. In fact, one of the most fascinating of Rouge‘s former issues, number five (2004), devoted itself exclusively to images selected by 52 contributors.

It’s fairly highbrow, and relatively austere in spite of its ingenious uses of images, so I can’t pretend that Rouge is geared to every taste.

Read more

The following is from the [London] National Film Theatre’s program guide in December-January 1975-76, introducing a retrospective that I curated. If the valuation that I placed on Altman seems more idealized to me now than it did at the time, the fact that it came shortly after his best run as a filmmaker explains much of my enthusiasm. But my disillusionment with the media support of Altman already began to sour after I described at length the use of sound in a particular sequence from California Split to a BBC-Radio interview, only to discover that the broadcast version blithely substituted a different sequence from the film to illustrate my point, thereby reducing my analysis to gibberish. -– J.R.

While most commercial American streamliners turn all members of an audience into second-class passengers following the same route from an identical vantage point, Robert Altman’s multilinear adventures oblige us to take some initiative in charting out the trip -– supplying one’s own connections, and pursuing one’s own threads and interpretations in order to participate in a game where everyone, on-screen and off, is entitled to a different piece of the action.

Admittedly, this is a somewhat idealized description of an approach that is still in a state of development, and not every Altman film conforms precisely to this model. Read more

I’m saddened that Andrew Sarris (1928-2012) didn’t live longer than 83, even though he had a very rich and rewarding career as a film critic.

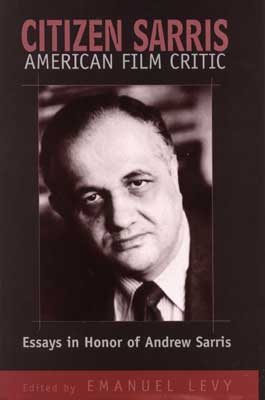

This book review appeared in the sixth issue of Cinema Scope (Winter 2001) and is reprinted in Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. — J.R.

The American Cinema Revisited

Citizen Sarris, American Film Critic:

Essays in Honor of Andrew Sarris

Edited by Emanuel Levy

The Scarecrow Press, 2001

Ironically, my enemies were the first to alert me to the fact that I had followers.

— Andrew Sarris, Confessions of a Cultist (1970)

One of the main emotions aroused in me by the 40 or so contributions to the millennial Festschrift Citizen Sarris is nostalgia –- specifically, a yearning for the era three or four decades ago when something that might be described as a North American film community was slowly emerging and recognizing its own existence.

This was just before academic film studies, radical politics, drugs and diverse other developments splintered that community into separate and mainly non-communicating cliques and ghettos, accompanied by an intensification of studio promotion that eventually took infotainment beyond its status as a minor industry and into an arena where advertising was coming close to defining as well as monitoring the whole of film culture, thus phasing out individual voices -– or at the very least bunching them together in sound bites, pull quotes, bibliographies and adjectival ad copy. Read more

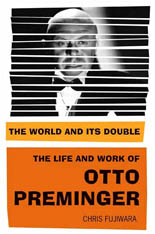

From Cineaste, Summer 2008 (Vol. XXXIII, No. 3). It’s gratifying that Such Good Friends has finally come out on DVD. — J.R.

The World and its Double: The Life and Work of Otto Preminger

by Chris Fujiwara. New York: Faber & Faber, 479 pp., illus. Hardcover: $35.00.

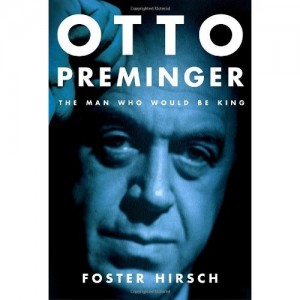

Otto Preminger: The Man Who Would Be King

by Foster Hirsch. New York: Alfred A, Knopf, 573 pp., illus. Hardcover: $35.00

Few film directors resist critical biography as much as Otto Preminger, given all the puzzling and intractable mismatches one encounters as soon as one tries to reconcile his very public life with his no less private body of work as an auteur. This is a difficulty acknowledged in the title and subtitle of Chris Fujiwara’s book, and one he essentially tries to resolve by splitting most of his chapters into two sections. But the overall disassociation of Preminger’s life and work, even though it’s addressed by this structure, still becomes a kind of structuring absence that haunts this biography as well as Foster Hirsch’s, which tries to integrate the two concerns more conventionally. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 23, 1996). — J.R.

Rumble in the Bronx

Directed by Stanley Tong

Written by Edward Tang and Fibe Ma

With Jackie Chan, Anita Mui, Francoise Yip, and Bill Tung.

Broken Arrow

Directed by John Woo

Written by Graham Yost

With John Travolta, Christian Slater, Samantha Mathis, Delroy Lindo, Bob Gunton, and Frank Whaley.

Many people who’ve seen Saturday Night Fever probably remember the poster of a bare-chested Sylvester Stallone as Rocky in the bedroom of Tony (John Travolta), the king of Brooklyn disco. But how many recall the poster of a bare-chested Bruce Lee as well? In the nearly two decades since Saturday Night Fever was released, the dream of wedding Hong Kong action pyrotechnics with Hollywood production values to conquer the American mainstream has surfaced periodically, but until recently the results have seemed halfhearted at best.

I haven’t seen any of the earlier Jackie Chan vehicles with American settings — films like The Big Brawl (1980) and The Cannonball Run (1981) — but it’s clear that none of these succeeded in turning Chan into an American household word. At most he’s become an alternative action hero for some passionate aficionados — especially in Chicago, where Barbara Scharres’s efforts at the Film Center to honor his work, climaxing in an in-person appearance a few years back, have helped to foster a growing cult. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 17, 2005). –J.R.

This fascinating oddity from Alain Corneau (Tous les matins du monde) adapts Amelie Nothomb’s autobiographical novel about the office life of a young Belgian (Sylvie Testud) working for a huge corporation in Tokyo. Though she’s spent her childhood in Japan and speaks fluent Japanese, a string of cultural blunders leads to one humiliating demotion after another. Testud took a two-month crash course in the language to play this part, and though the notations on cultural difference are far richer and subtler than anything in Lost in Translation, I can’t help but wonder what Japanese viewers might think of this film’s blistering critique of some of their hierarchies and protocol. The unconventional take on power and freedom, enriched by a deft use of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, remains that of an outsider. In Japanese and French with subtitles. 102 min. Music Box. Read more

The year before I started my Paris Journal for Film Comment, in late 1970 and/or early 1971, I wrote a couple of prototypes for it for a short-lived magazine, On Film, that didn’t survive long enough to print either one of them. In fact, On Film never made it past its lavishly glossy first issue, which was devoted mainly to Otto Preminger. Not all of either of these columns has survived either, but here is the first entry in the second of these columns, which did. — J.R.

November 6: Howard Hawks’s FIG LEAVES at the Cinémathèque.

Twenty days ago, I concluded my previous column with remarks about Ozu’s TOKYO STORY. Since then, I’ve seen or reseen a dozen films; Mizoguchi’s SISTERS OF THE GION and THE CRUCIFIED WOMAN, Franju’s THOMAS L’IMPOSTEUR, Kramer’s ICE, Malraux’s L’ESPOIR, Tati’s PLAYTIME, Demy’s THE YOUNG GIRLS OF ROCHEFORT, Minnelli’s CABIN IN THE SKY, Mankiewicz’s THERE WAS A CROOKED MAN, Godard’s MASCULIN-FEMININE, Ray’s BIGGER THAN LIFE, and now Hawks’s second film, a comedy made in 1926. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 22, 1990). — J.R.

THE GANG OF FOUR

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Jacques Rivette

Written by Rivette, Pascal Bonitzer, and Christine Laurent

With Bulle Ogier, Benoit Regent, Laurence Cote, Fejria Deliba, Bernadette Giraud, Ines de Medeiros, and Nathalie Richard.

SANTA SANGRE

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Alejandro Jodorowsky

Written by Jodorowsky, Roberto Leoni, and Claudio Argento

With Axel Jodorowsky, Blanca Guerra, Guy Stockwell, Thelma Tixou, Sabrina Dennison, Adan Jodorowsky, and Faviola Elenka Tapia.

In nearly half his films, 6 features out of 13, Jacques Rivette allows his characters only two possibilities. One is work in the theater, specifically rehearsals — an all-enveloping, all-consuming activity that essentially structures one’s life and assumes many of the characteristics of a religious order. The other, more treacherous possibility is involvement in a real or imagined conspiracy outside the theater — a plot or (the French term is more evocative) complot that is hard to detect yet seemingly omnipresent, sinister yet seductive for anyone who strays from the straight and narrow path offered by the rehearsals. Art versus life? Not exactly; a bit more like two kinds of art, or two kinds of life.

Both possibilities convey a sense of forging a fragile meaning over a gaping void. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 9, 1990). — J.R.

MYSTERY TRAIN

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Jim Jarmusch

With Youki Kudoh, Masatoshi Nagase, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Cinque Lee, Nicoletta Braschi, Elizabeth Bracco, Joe Strummer, and Rick Aviles.

Mastery is a rare commodity in American movies these days, in matters both large and small, so when a poetic master working on a small scale comes into view, it’s reason to sit up and take notice. Jim Jarmusch’s second feature, Stranger Than Paradise, won the Camera d’Or at Cannes in 1984 and catapulted him from the position of an obscure New York independent with a European cult following — on the basis of his first feature, Permanent Vacation (1980) — to international stardom.

As the first — and so far only — filmmaker informed by the New York minimalist aesthetic to make a sizable mainstream splash, Jarmusch had a lot riding on his next films, and he has acquitted himself admirably. He hasn’t sold out to Hollywood or diluted his style, and, unlike most of the few other contemporary American independents to make it big, he has managed to maintain rigorous control over every aspect of his work, from script to production to distribution. Read more

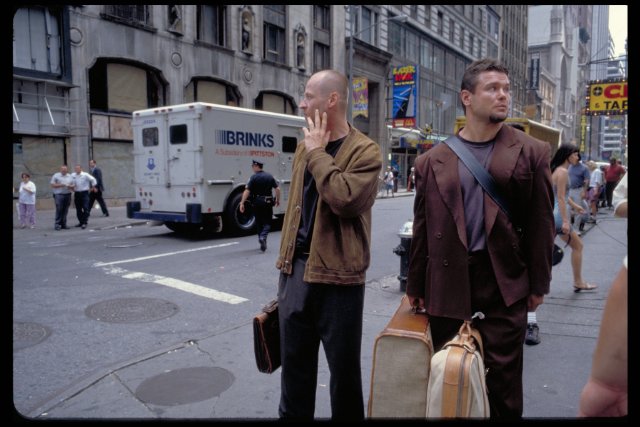

From the Chicago Reader (March 23, 2001). — J.R.

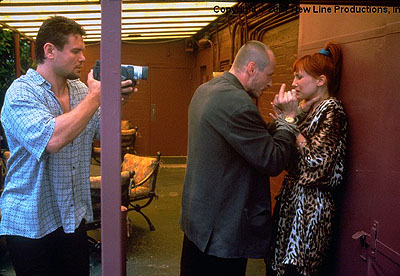

15 Minutes ***

Directed and written by John Herzfeld

With Robert De Niro, Edward Burns, Kelsey Grammer, Avery Brooks, Melina Kanakaredes, Karel Roden, and Oleg Taktarov.

A first-rate Hollywood entertainment, 15 Minutes is more than a little schizophrenic, a shotgun wedding between two seemingly irreconcilable genres — the buddy/cop action thriller and the angry social satire. It can’t even be unambiguous about the reason for its title. Presumably to placate the action-thriller buffs — some of whom are bound to be pissed off because satire is what closes in New Haven — there’s a throwaway line toward the end of the movie in which a vengeful cop is told he’ll have custody of the killer of his slain colleague for 15 minutes. Far more important is the satirical reference the movie bothers to cite only in the press notes: Andy Warhol’s 1968 assertion that “In the future everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.”

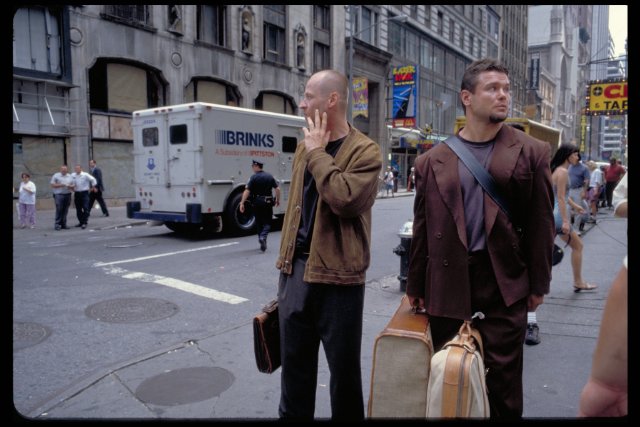

I’m a satire buff, but I have to confess that I do like at least a couple of the straight-ahead and relatively mindless action sequences: several cops chasing a Czech killer through busy midtown Manhattan traffic, while the killer, Emil, and his simpleminded Russian sidekick, Oleg (who videotapes everything and whose hero is Frank Capra), flee toward Central Park; and a fire marshal and a murder witness trying to escape from her apartment after it explodes in flames. Read more

One more photo of a family theater, this one taken at a war bond rally and furnished to me by my brother Alvin. My parents, standing on top of the marquee, are just above the letter E; my grandfather, on the ground, can be seen under the second S, in front of the one-sheet advertising the current attraction, Thank Your Lucky Stars. [2/17/11]

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 19, 2004). — J.R.

The Big Red One: The Reconstruction

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and Written by Samuel Fuller

With Lee Marvin, Mark Hamill, Robert Carradine, Bobby Di Cicco, Stephane Audran, Christa Lang, Kelly Ward, Siegfried Rauch, and Fuller

“When I enter his suite at the Plaza, he’s finishing lunch, expressing his regret about missing Godard in Cannes, remarking on the absurdity of prizes at film festivals, asking me what Soho News and Soho are. (The one he knows about is in London — he fondly recalls a cigar store on Frith Street.)

“It isn’t hard to figure out why Mark Hamill affectionately calls him Yosemite Sam, or why Lee Marvin simply says he’s D.W. Griffith. Bursting with the same charismatic, comic book energy that skyrockets through most of his movies, old crime reporter, novelist, war hero, writer-director and sometime producer Samuel Fuller, almost 69, still moves and talks like his daffy action flicks — like the wild man from Borneo — in quick, short, blocky punches, like two-fisted slabs of socko headline type.”

The purple prose was mine, the year was 1980. Fuller was promoting his semiautobiographical war picture The Big Red One, even though the studio had just cut half of it — something he wasn’t making any effort to hide. Read more

Two quotes from the Letters section of the February 3, 1977 New York Review of Books:

John Bernard Myers: “It can easily be demonstrated that film directors created this art: Méliès, D.W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Eisenstein, Pudovkin, G.W. Pabst, Fritz Lang, Abel Gance, René Clair, Robert Flaherty, Alfred Hitchcock, Louis Malle—the list is long.”

Gore Vidal: “[Peter] Bogdanovich’s list of Welles’s post-[Herman] Mankiewicz films as compared to Mankiewicz’s post-Welles films only proves that neither was to be involved in another good film (excepting The Magnificent Ambersons and Christmas Holiday) ever again. This is the not unusual fate of movie makers as I discovered, and as Bogdanovich is discovering. You almost can’t win.

“With characteristic wit, wisdom, and eloquence, John Myers proves my point that ever since the movies began to talk the writer, not the director, is the essential creator of any film. Mr. Myers lists the directors that he admires and except for Louis Malle, they are all silent film directors (Fritz Lang of course worked in both silent and sound). Are the movies really and truly an art form? Nolo contendere.”

It’s astonishing that Vidal should argue and apparently believe that we value Chaplin, Eisenstein, Clair, and even Hitchcock as artists, if at all, only when they made silent pictures — apparently unlike Fritz Lang, whose M is a talkie. Read more

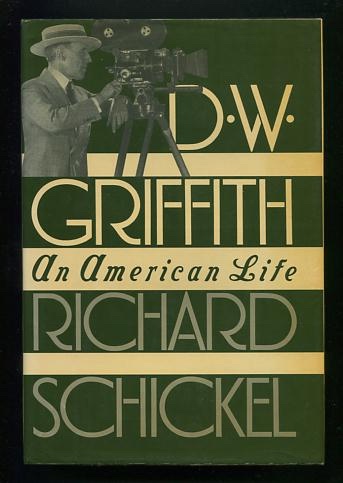

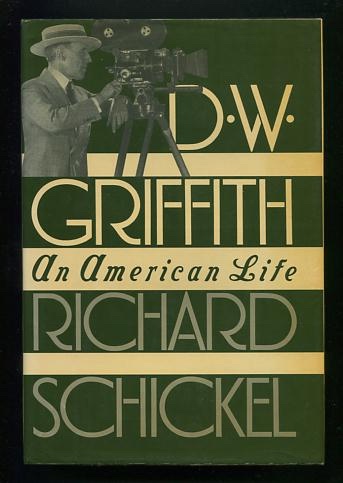

From Sight and Sound (Autumn 1984). –- J.R.

D.W. GRIFFITH: An American Life

by Richard Schickel

Pavilion, £15.00

Arriving on the heels of Donald Spoto’s Hitchcock and Richard Koszarski’s Stroheim, Richard Schickel’s massive biography of Griffith manages to steer a middle course between the compulsive narrative thrust of the former and the more scholarly negotiation of diverse hypotheses pursued by the latter. Grappling with a life and personality that surprisingly proves to be no less private and elusive than Hitchcock’s, Schickel confidently leads the reader through over six hundred pages of text without ever resorting to Spoto’s questionable tactic of baiting one’s interest with the promise of scandalous revelations. And if his scholarship in certain areas raises more questions than Koszarski’s -– see the helpful remarks of Griffith scholar Tom Gunning in the June American Film, particularly about the Biograph period -– he can still be credited with plausibly ploughing his way through an avalanche of contradictory and incomplete data.

Schickel’s task is, of course, more formidable than Spoto’s or Koszarski’s, encompassing some seventy-odd years and nearly five hundred films. Earlier efforts by Barnet Bravermann and Seymour Stern to compose a Griffith biography never reached completion (although Schickel has relied heavily on Bravermann’s material). Read more