The year before I started my Paris Journal for Film Comment, in late 1970 and/or early 1971, I wrote a couple of prototypes for it for a short-lived magazine, On Film, that didn’t survive long enough to print either one of them. In fact, On Film never made it past its lavishly glossy first issue, which was devoted mainly to Otto Preminger. Not all of either of these columns has survived either, but here is the first entry in the second of these columns, which did. — J.R.

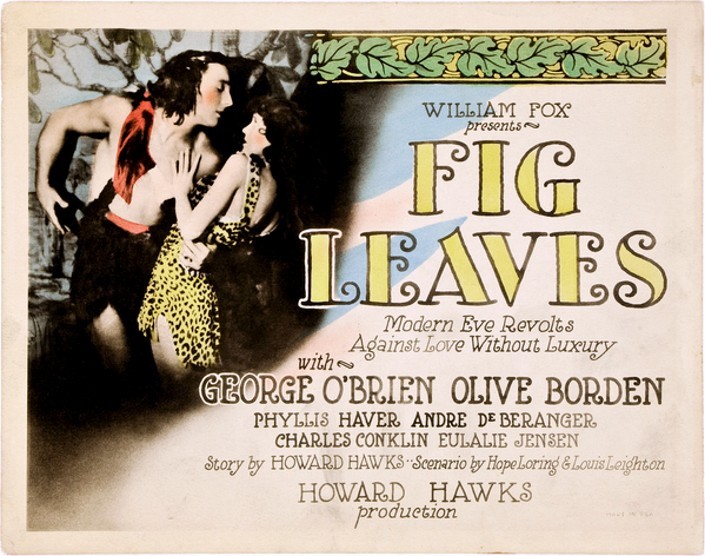

November 6: Howard Hawks’s FIG LEAVES at the Cinémathèque.

Twenty days ago, I concluded my previous column with remarks about Ozu’s TOKYO STORY. Since then, I’ve seen or reseen a dozen films; Mizoguchi’s SISTERS OF THE GION and THE CRUCIFIED WOMAN, Franju’s THOMAS L’IMPOSTEUR, Kramer’s ICE, Malraux’s L’ESPOIR, Tati’s PLAYTIME, Demy’s THE YOUNG GIRLS OF ROCHEFORT, Minnelli’s CABIN IN THE SKY, Mankiewicz’s THERE WAS A CROOKED MAN, Godard’s MASCULIN-FEMININE, Ray’s BIGGER THAN LIFE, and now Hawks’s second film, a comedy made in 1926. I may be inflicted with an overdose of Zeitgeist, but unless my eyes are deceiving me, it appears that Hawks’s movie is the first thing I’ve seen since TOKYO STORY that can fairly be called “non-political”. Everything else, from Mizoguchi’s Women’s Lib protests about geisha life to Ray’s nightmare rendering of American normality, seems to bear witness to a refusal to take the world as it is, whether it be through camp mortification (Demy), lyrical propaganda (Malraux, Godard), hysterical agit-prop (Kramer) or mindless transcendence (Minnelli). After such a mixed bag of directors, it is curious to confront someone who only cares about how goofy George O’Brien can look when he wants to.

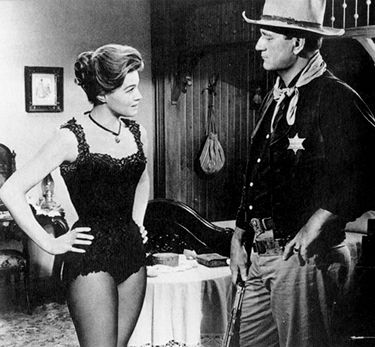

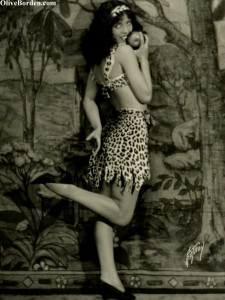

It is interesting to speculate about Hawks’s first film, THE ROAD TO GLORY -– made the same year as FIG LEAVES –- which no longer exists. In an interview with Peter Bogdanovich, Hawks said, “I was not in a very good frame of mind and wrote a complete tragedy. I was told it is not what people like to see, so I switched with my next picture.” Whatever happened to Hawks in the six months between THE ROAD TO GLORY and FIG LEAVES must surely merit a chapter in his unwritten biography. For the marvel of Hawks’s style in the latter film is how intact it has already become. It is unnerving to watch George O’Brien and Olive Borden stand and gesture in relation to one another with almost precisely the same set of mannerisms that John Wayne and Angie Dickinson will employ in RIO BRAVO thirty-three years later. The conclusion to be drawn from this is perhaps not so much “stylistic consistency” as the thought that Hawks inhabits another planet, a happy place where people always do the same crazy things and life never changes.

Such indeed is the central premise of FIG LEAVES, which begins with Adam and Eve living in Stone Age luxury, shifts to “the same couple” in modern times, and then blithely shuttles back again, with no change of behavior visible. The prehistoric sections are enlivened by a number of Keatonesque gags and gadgets, including a cute dinosaur who nibbles at trees and an “alarm clock” elaborately geared to drop coconuts on O’Brien’s head, while the modern sequences feature art nouveau décor and an extravagant fashion show. But such trappings, which Hawks always seems to borrow or steal from elsewhere, are ultimately nonessential to a serene and measured style that concerns itself, as always, with life in a vacuum.