From the Chicago Reader (February 23, 1996). — J.R.

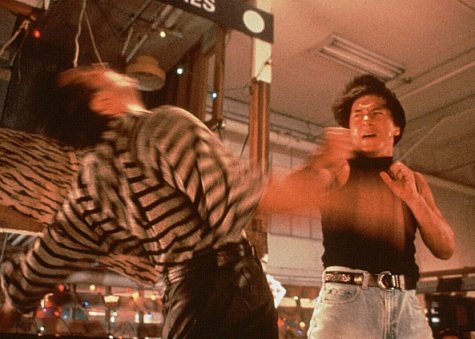

Rumble in the Bronx

Directed by Stanley Tong

Written by Edward Tang and Fibe Ma

With Jackie Chan, Anita Mui, Francoise Yip, and Bill Tung.

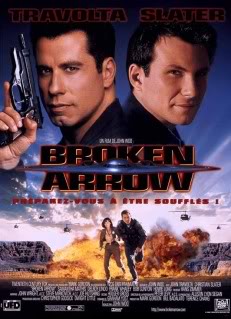

Broken Arrow

Directed by John Woo

Written by Graham Yost

With John Travolta, Christian Slater, Samantha Mathis, Delroy Lindo, Bob Gunton, and Frank Whaley.

Many people who’ve seen Saturday Night Fever probably remember the poster of a bare-chested Sylvester Stallone as Rocky in the bedroom of Tony (John Travolta), the king of Brooklyn disco. But how many recall the poster of a bare-chested Bruce Lee as well? In the nearly two decades since Saturday Night Fever was released, the dream of wedding Hong Kong action pyrotechnics with Hollywood production values to conquer the American mainstream has surfaced periodically, but until recently the results have seemed halfhearted at best.

I haven’t seen any of the earlier Jackie Chan vehicles with American settings — films like The Big Brawl (1980) and The Cannonball Run (1981) — but it’s clear that none of these succeeded in turning Chan into an American household word. At most he’s become an alternative action hero for some passionate aficionados — especially in Chicago, where Barbara Scharres’s efforts at the Film Center to honor his work, climaxing in an in-person appearance a few years back, have helped to foster a growing cult.

I did see Hong Kong director John Woo’s disappointingly routine American debut, Hard Target (1993), with Jean-Claude Van Damme — a fairly forgettable action exercise that, simply because it came from a Hollywood studio, got much more attention in the American press than all the earlier Woo pictures combined. It seemed at the time that Woo had had to give up most of what made him special in order to make this picture at all.

This month both Chan and Woo are back in the American mainstream for fresh tries; and from the looks of things, they’ve learned a bit from their previous mistakes. Though I don’t have much more than a nodding acquaintance with either action auteur, it seems that Chan in Rumble in the Bronx has succeeded at making a personal project in the Hong Kong manner in a putatively American setting, while Woo in Broken Arrow has made a slam-bang Hollywood picture in which personal touches are visible, if mainly applied with an eyedropper. To my taste, however, neither film comes close to Chan’s or Woo’s best work: in terms of choreographic and musical invention, Rumble in the Bronx pales alongside Chan’s Drunken Master II (1978), and Broken Arrow, though it’s often better conventional entertainment than Woo’s earlier films, lacks most of the campy mannerisms that made them so singular.

This is not to suggest that the aims of these two filmmakers are similar. From the evidence of these pictures, it’s clear that Woo wants to make Hollywood movies while Chan wants to go on making Chinese ones. (One circumstantial link between them, however, is the fact that the Hong Kong studio behind Rumble in the Bronx, the venerable Golden Harvest, employed Woo between 1973 and 1983 — during which time he directed Chan in his first major role, in the 1975 The Hand of Death, and came into prominence with a string of eight hit comedies.)

Four days after seeing Rumble in the Bronx, I can remember only traces of the plot and characters — something to do with Chan, playing a Hong Kong cop, visiting New York to attend his uncle’s wedding to a large black woman and encountering various south Bronx rumbles along the way. (Though the interracial marriage is a far from conventional plot detail in American action films, the movie plays it strictly as the stuff of boulevard farce, harping on its “cuteness” and seeming incongruity.) But in all the Chan pictures I’ve seen plot and characters are invariably lightweight and perfunctory, basically just giving the stunts some context. Though Chan writes and/or directs some of his pictures, he’s known almost exclusively as a performer; the fact that the credited director of Drunken Master II, Lar Kar-leung, was fired by Chan halfway through the shooting seems not to have affected the results at all. By and large, watching a Chan movie is very much like attending a circus: the acrobatic stunts, however impressive, rarely seem anything other than physical feats. Awesome as spectacle but fairly perishable as anything else, Chan’s stunts are for me a far cry from the more dreamlike feats of Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, physical actors to whom he’s often compared.

You’re likely to retain from Rumble in the Bronx not plot but images: two female bikers racing at night over the tops of two facing rows of cars, a collapsing building, a death-defying leap from one building to another (executed, like most Chan stunts, without doubles or trickery), an attack of bat- and bottle-swinging villains on motorbikes. Most of the dubbing of the Chinese leads is exceptionally crude — evidently they delivered their dialogue in Cantonese — and only the few American characters are blessed with plausible lip sync. Most of the shooting took place in Vancouver, which explains the occasional incongruity of mountains in the Bronx. But dialogue and setting in this movie are finally less important than certain facts about its production: according to the movie’s press materials, both Chan and director Stanley Tong “finished the film on crutches,” and two stuntwomen as well as actress Francoise Yip broke their legs during the motorcycle tricks. Ultimately Chan’s accomplishments, however breathtaking, seem to have more to do with the Guinness Book of World Records than they do with the history of art — though it’s worth adding that, according to the New York Times, Rumble in the Bronx was the number-one box-office hit in mainland China last year.

The title of Broken Arrow comes from the military jargon for a lost nuclear weapon. As one character remarks during the movie, “I don’t know what’s scarier–the fact that there are missing nuclear weapons, or that it happens so often that there’s actually a term for it.” If this implies to you that the movie has anything resembling a political agenda about the billions of dollars our country wastes on nuclear weapons, think again; if anything this movie, like so many other American romps, leaves us with the impression that American nuclear weapons are essential to our well-being, for where would American action thrillers be without them?

The homoerotic themes that have been associated with John Woo’s best-known Hong Kong action thrillers are basically carryovers from the work of the late French cult director Jean-Pierre Melville, to whom Woo’s 1989 The Killer is explicitly dedicated. As Woo lists them himself, his themes are “tragic friendship, loyalty, betrayal, and honor”–to which he gives campy and mannerist inflections (in contrast, Melville’s “chamber” pieces are underplayed and relatively ironic). Broadly speaking, Woo is to Melville (or to Walter Hill, another Melville disciple) what Brian De Palma is to Alfred Hitchcock. But in terms of style, as opposed to themes, Woo and Melville aren’t much alike. Woo’s Hong Kong thrillers treat violence choreographically, as if shoot-outs were musical numbers, whereas Melville’s treatments of violence are relatively abbreviated, incidental to his other concerns.

In Broken Arrow, the classic Melville-Woo themes are not so much developed as simplified into a “friendly” sparring match between the two male leads, hero Christian Slater and villain John Travolta. (A literal sparring match, in fact, begins the movie.) Both are military pilots assigned to take a secret B-3 Stealth bomber on a test run–but then Travolta hijacks two nuclear warheads in order to exact a ransom from the Pentagon, and Slater (assisted by park ranger Samantha Mathis, also his costar in Pump Up the Volume) contrives to save the day. The fact that Travolta’s evil character seems unmotivated by anything but his macho rivalry with Slater is just about the only vestige of Woo’s usual themes. Otherwise the main auteurist input seems to come from screenwriter Graham Yost, whose script for Speed was another simpleminded bomb-about-to-go-off exercise but without the male bonding. The main carryover from Woo’s Hong Kong thrillers is the elegant sense of craft in his articulation of action sequences, though the degree of stylization is much less: Woo specialties, like slow motion, tend to be restricted to short individual shots rather than taking up whole sequences. In short, Woo’s determination to make a Hollywood blockbuster has entailed a reduction of his artistic role, from an auteur to a craftsman with personal touches. To my mind that’s a reasonable trade-off, because the sheer grotesquerie of his hysterical if much-applauded sub-Melville thrillers often interfered with my enjoyment of their formal aspects. Here the spectacular canyon landscapes and the resourceful uses of cars, planes, boats, and trains traversing them are part of this artful if highly disposable entertainment, not anything that qualifies as personal expression.

Another reason for Woo’s reduced role is undoubtedly the extensive, lavish special effects: the film works wonders not only with a crashing helicopter but also with the rolling earth tremors like tidal waves that follow a nuclear explosion. I’m reminded of the degree to which John Carpenter, another able genre craftsman, lost some creative control on his remake of The Thing to the makeup and effects specialists, though in the case of Broken Arrow the loss may be salutary: by and large this picture represents collaborative Hollywood action filmmaking at its best.

Part of the kick being offered is the novelty of watching Travolta as a dyed-in-the-wool villain–not a believable or coherent character, but still it’s amusing to hear Travolta’s fine, teeth-clenched delivery of the line “Would you mind not shooting at the thermonuclear weapons?” Better yet, the way these performers — Travolta, Slater, Mathis — adapt to their action roles here though they’re not usually action performers (Slater does a good many of his own stunts, for instance) again demonstrates how individual personalities are subsumed by the collaborative requirements of the Hollywood pleasure machine. Broken Arrow is beautifully crafted, mindless entertainment — nothing more, but also nothing less.