This was written in the summer of 2000 for a coffee-table book edited by Geoff Andrew that was published the following year, Film: The Critics’ Choice (New York: Billboard Books). — J.R.

A joint effort by French ethnographer-filmmaker Jean Rouch and French sociologist Edgar Morin (The Stars) yielded this remarkable 1961 documentary investigation into what Parisians — regarded as a “strange tribe” — were thinking and feeling during the summer of 1960. This was when the war in Algeria was still a hot issue, although many other topics are discussed as well, private as well as public. At first, everyone is asked, simply, “Are you happy?” More generally, the film catches the shifting emotional tenor of a few lives over a certain period.

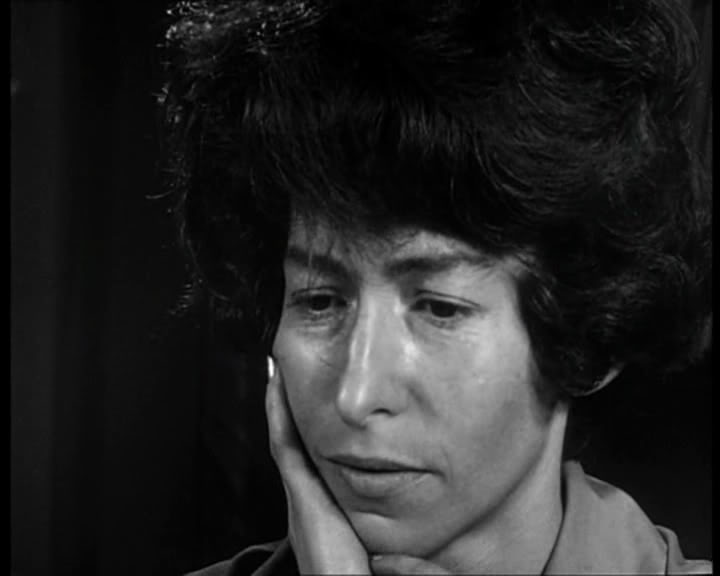

The filmmakers treat their interview subjects with a great deal of respect and sensitivity. Among them are Marilou, an Italian emigre working as a secretary at Cahiers du Cinéma; a French student named Jean-Pierre; a factory worker named Angelo; an African student named Landry; a painter and his wife named Henri and Maddie; and a pollster named Marceline assisting with some of the other interviews.

Not only do we see these individuals in diverse groupings, even on holiday in St.-Tropez; we also see many of them becoming friends over the course of the film. Finally, Rouch and Morin screen a rough cut for the participants and film their highly divergent responses, then shoot their own auto-critique as they stroll together through the Musée de l’homme.

The biggest surprise about this seminal work is that even though it’s made by two eminent social scientists, its value winds up having relatively little to do with either anthropology or sociology. Rouch as a filmmaker had already discovered in his innovative African documentaries that you best catch people “being themselves” if you film them “playing themselves,” and this film is actually a kind of home movie about life being lived and self-consciously performed by these touching individuals in interaction with one another and in front of the camera.

We soon learn that Marceline — who years later would become the companion and codirector of Joris Ivens, the great Dutch documentarist — picked Jean-Pierre as an interview subject because he’s a former boyfriend, and her feelings about their failed relationship become part of the ongoing discussion. The first time Marilou speaks to Morin, she’s lonely and on the edge of tears; the second time she’s much happier and we briefly glimpse her with her boyfriend when they go out for a walk (Jacques Rivette, as it happens, with whom she would later write scripts). Rouch asks Landry if he understands the meaning of the tattoo on Marceline’s arm, and she goes on to explain that she’s a Jewish concentration camp survivor. Even more than his ethnographic works about Africans, Chronicle makes it evident in its graceful spontaneity why Rouch was a key influence on the French New Wave, so it isn’t surprising to discover in the closing credits that Raoul Coutard — the key cinematographer of that movement, who shot most of the first features of Godard, Truffaut, and Demy — worked on this film as well.