This was written in the summer of 2000 for a coffee-table book edited by Geoff Andrew that was published the following year, Film: The Critics’ Choice (New York: Billboard Books). — J.R.

A joint effort by French ethnographer-filmmaker Jean Rouch and French sociologist Edgar Morin (The Stars) yielded this remarkable 1961 documentary investigation into what Parisians — regarded as a “strange tribe” — were thinking and feeling during the summer of 1960. This was when the war in Algeria was still a hot issue, although many other topics are discussed as well, private as well as public. At first, everyone is asked, simply, “Are you happy?” More generally, the film catches the shifting emotional tenor of a few lives over a certain period.

The filmmakers treat their interview subjects with a great deal of respect and sensitivity. Among them are Marilou, an Italian emigre working as a secretary at Cahiers du Cinéma; a French student named Jean-Pierre; a factory worker named Angelo; an African student named Landry; a painter and his wife named Henri and Maddie; and a pollster named Marceline assisting with some of the other interviews.

Not only do we see these individuals in diverse groupings, even on holiday in St.-Tropez; Read more

From Cinema Scope (Spring 2003). — J.R.

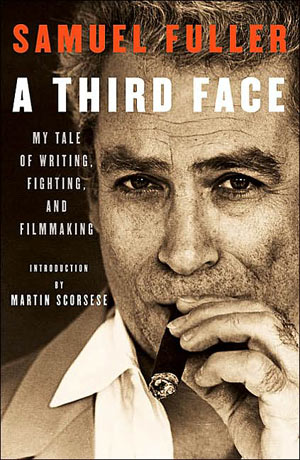

A Third Face: My Tale of Writing, Fighting, and Filmmaking by Samuel Fuller. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

Thank God for Beethoven’s music. Ludwig got me though a lot of rough times. He said, “Music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy.” Holy cow, was he right! — photo caption in A Third Face

Checking my appointment book for 1980, I see that I met Sam Fuller for the first time on June 19, in New York. It was in a suite at the Plaza, where I went to interview him about The Big Red One for the Soho News, and from the moment a publicist opened the door and I was greeted by this short, peppy firecracker, he was already outlining a movie sequence in which I was being kidnapped by a team of Amazons, with the publicist instantly cast as one of the members of the team.

The interview itself was a collection of comparable verbal cadenzas, about life and commerce as well as cinema — with occasional off-the-record asides, like asking me at one point if I’d seen Jean-Luc Godard’s Made in USA, and what I thought of it. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1988). — J.R.

The revisionist view of this 1940 adaptation by John Ford and Dudley Nichols of four one-act plays by Eugene O’Neill downgrades it in favor of the once-neglected Ford westerns — in large part because, unlike the westerns, it was widely praised when it first came out. But it’s about time to restore some balance and recognize this film as a remarkable achievement. This rambling, melancholy tale of merchant seamen and their lonely lives features arguably the best cinematography by Gregg Toland outside of Citizen Kane, and apart from the very special case of Lumet’s reading of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, O’Neill’s finest work, it’s certainly the best realization of O’Neill’s vision on film. It’s also as personal and as deeply felt as any of the more recently canonized Ford masterpieces, and does more with the expressionistic style he often adopted during this period than many of his better-known works. The ensemble acting is extraordinary; John Wayne turns in one of his few successful actorly performances as a Swede, and Thomas Mitchell, Barry Fitzgerald, Ian Hunter, Ward Bond, Mildred Natwick, John Qualen, and Joe Sawyer are equally impressive. The display of emotion here is more direct than is usual with Ford, but the dreamy atmospherics provide an ideal container for this raw feeling. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 1, 1989). — J.R.

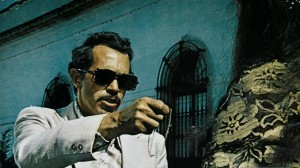

By far the most underrated of Sam Peckinpah’s films, this grim 1974 tale about a minor-league piano player (Warren Oates) in Mexico who sacrifices his love (Isela Vega) when he goes after a fortune as a bounty hunter is certainly one of the director’s most personal and obsessive works — even comparable in some respects to Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano in its bottomless despair and bombastic self-hatred, as well as its rather ghoulish lyricism. (Critic Tom Milne has suggestively compared the labyrinthine plot to that of a gothic novel.) Oates has perhaps never been better, and a strong secondary cast — Vega, Gig Young, Robert Webber, Kris Kristofferson, Donnie Fritts, and Emilio Fernandez — is equally effective in etching Peckinpah’s dark night of the soul. R, 112 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

It’s taken a lot of work, but I’ve finally managed to compile an index of all, or almost all, of my long reviews that were published in the Chicago Reader between the fall of 1987 and the fall of 2009, nearly all of which are on this site. This index can be accessed here, or, better yet, under Notes (dated 6 February 2010), where direct links are provided, and I hope it makes some of the contents of this site more user-friendly and accessible. It’s basically organized alphabetically by film titles, or, in a few cases, by subjects or book titles. I haven’t provided links, but these reviews can be searched out by either film title or (which may be easier) by dates in the right-hand column.

I doubt that I’ll ever compile a similar list of all my capsule (i.e., one-paragraph) reviews for the Reader on this site, which would be much, much longer, but I should add that a separate index of all my longer non-Reader pieces, chronologically rather than alphabetically ordered, can already be found at “About This Site”, and at some future date I may index those pieces alphabetically as well. [2/7/10] Read more

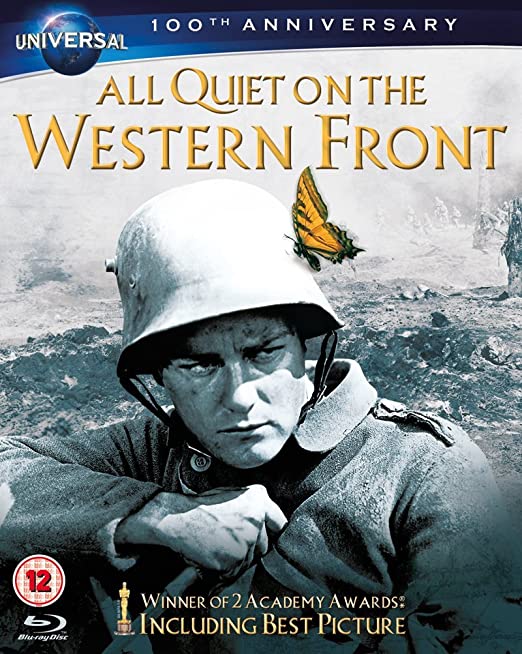

Lewis Milestone’s powerful 1930 adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s antiwar novel, starring Lew Ayres and Louis Wolheim, deserves its reputation as a classic. The sound version originally ran 140 minutes, though ultimately (and unfortunately) the studio eliminated about 35 of them. Most of the missing footage was subsequently restored in a combined effort by various archives, and at 132 minutes the film can now be seen for the remarkable work that it is. Milestone’s other 30s work (e.g., Hallelujah, I’m a Bum!) is sorely in need of reappraisal. (JR)

Read more