From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1989). — J.R.

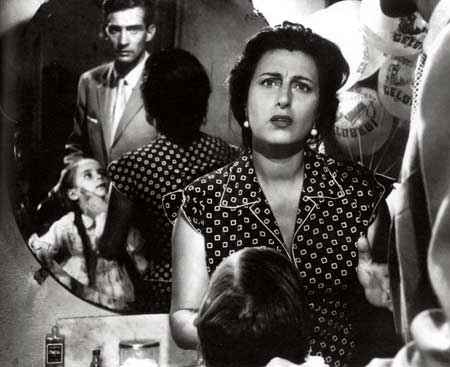

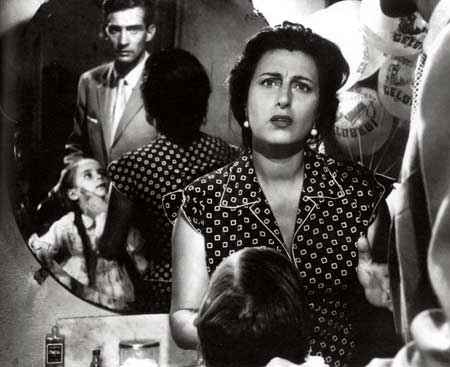

Perhaps the most unjustly neglected of Luchino Visconti’s early films is this hilarious 1951 comedy, tailored to the talents of Anna Magnani, about a working-class woman who is determined to get her plain seven-year-old daughter into movies. A wonderful send-up of the Italian film industry and the illusions that it fosters, delineated in near-epic proportions with style and brio. With Walter Chiari and Alessandro Blasetti. (JR) Read more

This was written in the summer of 2000 for a coffee-table book edited by Geoff Andrew that was published the following year, Film: The Critics’ Choice (New York: Billboard Books). — J.R.

There’s something approaching a consensus, shared by the filmmaker himself, that the best of Claude Chabrol’s early features is Les bonnes femmes (1960), his fourth. Yet the film was a box office flop when it first appeared, widely attacked in France and elsewhere for being ugly, misanthropic, and cynical. And it might be fair to say that this response wasn’t so much superseded as reinterpreted in the years to come. For Les bonnes femmes is probably Chabrol’s most pessimistic work, harping relentlessly on vulgarity, boorishness, and cruelty. Focusing on four young woman who work from nine to seven at an electrical appliance store in Paris, the film offers a definitive look at what they want from life and how poorly they fare in their aspirations — culminating in a remarkable, ambiguous final sequence set in a dancehall, leaving everything up to the audience’s troubled imagination, about another young woman who isn’t identified at all dancing with an equally unidentified stranger.

Jane (Bernadette Lafont), the shopgirl who visibly expects the least from life, goes out carousing with a couple of men in an early sequence and virtually gets raped. Read more

This was written in the summer of 2000 for a coffee-table book edited by Geoff Andrew that was published the following year, Film: The Critics’ Choice (New York: Billboard Books). — J.R.

A joint effort by French ethnographer-filmmaker Jean Rouch and French sociologist Edgar Morin (The Stars) yielded this remarkable 1961 documentary investigation into what Parisians — regarded as a “strange tribe” — were thinking and feeling during the summer of 1960. This was when the war in Algeria was still a hot issue, although many other topics are discussed as well, private as well as public. At first, everyone is asked, simply, “Are you happy?” More generally, the film catches the shifting emotional tenor of a few lives over a certain period.

The filmmakers treat their interview subjects with a great deal of respect and sensitivity. Among them are Marilou, an Italian emigre working as a secretary at Cahiers du Cinéma; a French student named Jean-Pierre; a factory worker named Angelo; an African student named Landry; a painter and his wife named Henri and Maddie; and a pollster named Marceline assisting with some of the other interviews.

Not only do we see these individuals in diverse groupings, even on holiday in St.-Tropez; Read more

From Cinema Scope (Spring 2003). — J.R.

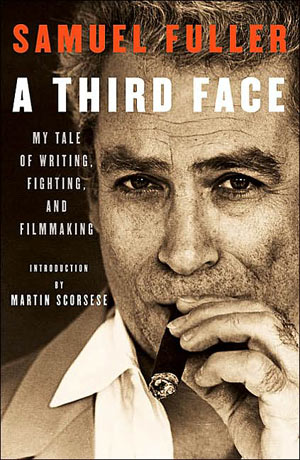

A Third Face: My Tale of Writing, Fighting, and Filmmaking by Samuel Fuller. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

Thank God for Beethoven’s music. Ludwig got me though a lot of rough times. He said, “Music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy.” Holy cow, was he right! — photo caption in A Third Face

Checking my appointment book for 1980, I see that I met Sam Fuller for the first time on June 19, in New York. It was in a suite at the Plaza, where I went to interview him about The Big Red One for the Soho News, and from the moment a publicist opened the door and I was greeted by this short, peppy firecracker, he was already outlining a movie sequence in which I was being kidnapped by a team of Amazons, with the publicist instantly cast as one of the members of the team.

The interview itself was a collection of comparable verbal cadenzas, about life and commerce as well as cinema — with occasional off-the-record asides, like asking me at one point if I’d seen Jean-Luc Godard’s Made in USA, and what I thought of it. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1988). — J.R.

The revisionist view of this 1940 adaptation by John Ford and Dudley Nichols of four one-act plays by Eugene O’Neill downgrades it in favor of the once-neglected Ford westerns — in large part because, unlike the westerns, it was widely praised when it first came out. But it’s about time to restore some balance and recognize this film as a remarkable achievement. This rambling, melancholy tale of merchant seamen and their lonely lives features arguably the best cinematography by Gregg Toland outside of Citizen Kane, and apart from the very special case of Lumet’s reading of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, O’Neill’s finest work, it’s certainly the best realization of O’Neill’s vision on film. It’s also as personal and as deeply felt as any of the more recently canonized Ford masterpieces, and does more with the expressionistic style he often adopted during this period than many of his better-known works. The ensemble acting is extraordinary; John Wayne turns in one of his few successful actorly performances as a Swede, and Thomas Mitchell, Barry Fitzgerald, Ian Hunter, Ward Bond, Mildred Natwick, John Qualen, and Joe Sawyer are equally impressive. The display of emotion here is more direct than is usual with Ford, but the dreamy atmospherics provide an ideal container for this raw feeling. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 1, 1989). — J.R.

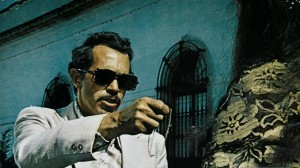

By far the most underrated of Sam Peckinpah’s films, this grim 1974 tale about a minor-league piano player (Warren Oates) in Mexico who sacrifices his love (Isela Vega) when he goes after a fortune as a bounty hunter is certainly one of the director’s most personal and obsessive works — even comparable in some respects to Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano in its bottomless despair and bombastic self-hatred, as well as its rather ghoulish lyricism. (Critic Tom Milne has suggestively compared the labyrinthine plot to that of a gothic novel.) Oates has perhaps never been better, and a strong secondary cast — Vega, Gig Young, Robert Webber, Kris Kristofferson, Donnie Fritts, and Emilio Fernandez — is equally effective in etching Peckinpah’s dark night of the soul. R, 112 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

It’s taken a lot of work, but I’ve finally managed to compile an index of all, or almost all, of my long reviews that were published in the Chicago Reader between the fall of 1987 and the fall of 2009, nearly all of which are on this site. This index can be accessed here, or, better yet, under Notes (dated 6 February 2010), where direct links are provided, and I hope it makes some of the contents of this site more user-friendly and accessible. It’s basically organized alphabetically by film titles, or, in a few cases, by subjects or book titles. I haven’t provided links, but these reviews can be searched out by either film title or (which may be easier) by dates in the right-hand column.

I doubt that I’ll ever compile a similar list of all my capsule (i.e., one-paragraph) reviews for the Reader on this site, which would be much, much longer, but I should add that a separate index of all my longer non-Reader pieces, chronologically rather than alphabetically ordered, can already be found at “About This Site”, and at some future date I may index those pieces alphabetically as well. [2/7/10] Read more

Lewis Milestone’s powerful 1930 adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s antiwar novel, starring Lew Ayres and Louis Wolheim, deserves its reputation as a classic. The sound version originally ran 140 minutes, though ultimately (and unfortunately) the studio eliminated about 35 of them. Most of the missing footage was subsequently restored in a combined effort by various archives, and at 132 minutes the film can now be seen for the remarkable work that it is. Milestone’s other 30s work (e.g., Hallelujah, I’m a Bum!) is sorely in need of reappraisal. (JR)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader, March 29, 1991. —J.R.

L’ATALANTE

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jean Vigo

Written by Vigo, Albert Riera, and Jean Guinee

With Michel Simon, Dita Parlo, Jean Dasté, Gilles Margaritis, and Louis Lefevre.

“What was Vigo’s secret? Probably he lived more intensely than most of us. Filmmaking is awkward because of the disjointed nature of the work. You shoot five to fifteen seconds and then stop for an hour. On the film set there is seldom the opportunity for the concentrated intensity a writer like Henry Miller might have enjoyed at his desk. By the time he had written twenty pages, a kind of fever possessed him, carried him away; it could be tremendous, even sublime. Vigo seems to have worked continuously in this state of trance, without ever losing his clearheadedness.” — François Truffaut, 1970

L’Atalante is one of the supreme achievements in the history of cinema, and its recent restoration, playing this week at the Music Box, offers what is surely the best version any of us is ever likely to see. Yet the conditions that made this masterpiece possible were anything but auspicious.

When Jean Vigo started to work on his first and only feature in July 1933, he had no say over either the script or the two lead actors. Read more

Originally posted on June 13, 2016. — J.R.

It’s embarrassing for me to confess that I let over six weeks pass from the time that Oda Kaori sent me an email from Osaka with a link to her 68-minute film Aragane until I finally found time to watch it — during a day of rest in Lisbon, in between professional engagements. This has been an exceptionally busy spring for me in terms of writing, travel, and other commitments, but I suspect that another reason why it’s taken me so long was the fearful prospect of watching a documentary of that length about work in a coal mine in Sarajevo. I don’t know why this prospect discouraged me so much, but the fault is mine.

Kaori was one of the original dozen or so students to enroll in Béla Tarr’s Film.Factory when it started three years ago, whom I met during my first of my four two-week sessions there; she was also one of the students most affected by the films of Peter Thompson, whose email I quoted from in my article about Film.Factory, and whom I once lent a DVD of Maya Deren’s films at her request. I believe that Aragane was her thesis film; she has shown it at a few Japanese venues, including the Yamagata film festival, and she is hoping to find a distributor for it. Read more

Written for the catalogue of Il Cinema Ritrovato, June-July 2016. — J.R.

Apocalypse Now

Like much of Coppola’s best work -– The Conversation, the Godfather trilogy, Bram Stoker’s Dracula –- Apocalypse Now teeters on the edge of greatness, and perhaps it wouldn’t teeter at all if greatness weren’t so palpably what it was lusting after. To my mind it functions best as a series of superbly realized set pieces bracketed by a certain amount of pretentious guff, some of which could be traced back to Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness, the movie’s point of departure, as well as some powerful voiceover narration written by Michael Herr, whose book Dispatches offered some authentic glimpses of the war from the American side. Much of the guff, I would argue, stems from the fact that Coppola never quite worked out what he wanted to say, a fact he often acknowledged at the time. Indeed, Coppola’s continuing doubt is a major element of the saga being celebrated here: the Passion of the Artist writ large, made to seem far more important than the mere suffering and deaths of a few hundred thousand nameless and faceless peasants (and American soldiers) across the South China Sea. Read more

From Cinema Scope No. 50, Winter 2012, as part of a feature, “50 Best Filmmakers Under 50”. — J.R.

Many reviewers of Azazel Jacobs’ four features understandably place them in a direct lineage from his father Ken’s work. Both filmmakers are clearly preoccupied with interactions and crossovers between fiction and nonfiction — although the same could be said of everyone from Lumière, Méliès, and Porter to Costa, Hou, and Kiarostami. And both are remarkable directors of actors/performers, even though, in the case of Ken, projectors and found footage have performative roles along with people. The dialectics forged by opposite coasts and mindsets — corporate Hollywood vs. flaky New York Underground, claustrophobic obsession/fixation versus airy and uncontrollable street theatre — are equally constant.

Most reviewers are quick to point out that Azazel is more committed to narrative than his father. It’s easy to see what they mean, but some of their assumptions are worth questioning. If part of what we mean by “narrative” is plot and incident, there may be more of both contained in the intertitles of Ken’s The Whirled (1956-63) than there is in the main action of Azazel’s second feature The GoodTimes Kid (2005). If part of what we mean is “character,” then the work of both filmmakers is overflowing with it, from Jack Smith’s manic cavorting in many of Ken’s films to Diaz’s exhilarating dance in The GoodTimes Kid, not to mention John C. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1996). This film is now readily available in the U.S. and the U.K., and while writing an essay about it for the Criterion release, I came to treasure it a lot more than I did when I wrote this capsule. — J.R.

This rarely screened hour-long Isak Dinesen adaptation by Orson Welles — his first release in color (1968), originally intended for a never-completed anthology film — is far from one of his most achieved works. But thematically and poetically it exemplifies his late lyrical manner, and it provides clues as to what his most treasured late project — another Dinesen adaptation called The Dreamers, for which he shot a few tests — might have looked like. Set in 19th-century Macao (though filmed modestly in France and Spain), this parablelike tale stars Welles as a lonely and selfish merchant who gets his Jewish secretary (Roger Coggio) to hire a courtesan (Jeanne Moreau) and a sailor (Norman Eshley) to reenact a story. It’s awkward in spots yet exquisite. (JR)

Read more

Read more

In my more than 20 years at the Chicago Reader, whenever an old film came to town that had a Reader capsule on file by Dave Kehr, my long-term predecessor at that paper (who left the paper in the mid-1980s), I always had the option of either using that old capsule or writing a new one. On almost every occasion when this happened, I opted for the former — for my money, Dave was and is the best capsule reviewer in the business, bar none. But when it came to The Best Years of Our Lives, I eventually decided that I had to write a new one. Below are the two capsules in question:

Perceived in 1946 (to the tune of nine Academy Awards) as a sign that the movies had finally “grown up,” William Wyler’s study of a group of men returning to civilian life after the war was a tremendous commercial success and helped to create Hollywood’s postwar highbrow style of pseudorealism and social concern. The film is very proud of itself, exuding a stifling piety at times, but it works as well as this sort of thing can, thanks to accomplished performances by Fredric March, Myrna Loy, and Dana Andrews, who keep the human element afloat. Read more

This book review, which I’ve alluded to previously on this site, appeared in the November 2, 1980 issue of The Soho News. —J.R.

Under the Sign of Sontag

Under the Sign of Saturn

By Susan Sontag

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $10.95

If, dialectically speaking, every book can be said to have an unconscious — a repressed subtext — one can find glimpses of the unconscious of this one in the misleading flap copy that quotes from an interview (“Women, the Arts, and the Politics of Culture,” Salmagundi 31-32) and mentions the inclusion of a “famous exchange on fascism and feminism” (apparently with Adrienne Rich, in the March 20, 1975 New York Review of Books), both regrettably missing from this slim volume of seven essays.

These omissions betray the absence of a gritty, indecorous social context — a sense of Sontag existing in the world, not merely staging grand Platonic shadow-plays in the theater of her mind. Much as Illness as Metaphor (1978) was partially structured around her refusal to allude once to her own personal struggle, this book discreetly, indirectly dances around the notion that the subject of every essay proposes a different kind of mirror to the author, a speculative self-portrait. Read more