This appeared in the January 6, 2006 issue of Chicago Reader. For some reason, it appears to have eluded the Reader’s web site archive, apart from its title, and therefore escaped this web site as well, until I found a way of pasting it in. — J.R.

The Best Film of the Past Two Years

And 24 more picks from what the industry thought us yokels could handle in 2005

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

To choose the best movies of 2005 is to compromise. I limit my list of candidates to films that have screened in Chicago, but I could easily fill it with movies that haven’t screened in the U.S. at all, and God knows what I’ve missed altogether. I’m at the mercy of studio heads, distributors, and publicists, whose decisions about what to release and when defy comprehension.

I saw Woody Allen’s Match Point in Madrid in mid- November, believing the distributor’s announcement that it would open in Chicago in December. Surprised at how much I liked it, I decided it probably belonged on my list, but then some industry executives decided that only the people in New York and Los Angeles should get to see it this year (in time for Oscar nominations), not the less discriminating moviegoers in the Chicago boondocks. I also couldn’t consider other films that won’t open here until 2006, such as Tommy Lee Jones’s The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada.

The people who run Disney spent a fortune sending critics and Academy members security-encoded DVDs with special “high end” players to view them on. Once we register the players we can watch the five films we’ve received so far as often as we like, though each time we do, according to the instructions, “the SV300 inserts a powerful, completely invisible watermark. It stamps the content with your player’s ID number, and the time and date of the recording. If the playback is copied illegally to videotape, recordable DVD, or onto the Internet, Cinea will be able to analyze the copy and identify the player, the time, and the date on which the copy was made.” Unfortunately, these players aren’t high-end enough to be region free, and the version of Howl’s Moving Castle they sent me is the same old dubbed one I’d already reviewed. The Japanese original with English subtitles won’t be out commercially on DVD until March. I can’t consider that version here because I haven’t seen it, so I’ve grudgingly put the dubbed version on my list.

These complaints aside, 2005 was a good enough year that my top ten list expanded to 15, including ties.

1.The World. Not just the best film of 2005, Jia Zhangke’s feature was better, or at least more important, than my first choices for 2004 (The Big Red One) and 2003 (25th Hour and Crimson Gold). Those earlier masterpieces lack its vital and complex vision of what the whole planet is like at the moment.

Jia’s greatest film, Platform (2002), is about the Cultural Revolution; The World is a superb companion piece about China’s recent capitalist revolution, set in a theme park outside Beijing with scaled-down models of the world’s most famous tourist attractions and populated by visitors and workers. It’s a kitsch monstrosity that Jia makes endlessly fascinating and suggestive — in contrast to the cramped and unattractive “backstage” living spaces where the main characters spend most of their time when they’re not working. The animated fantasies sparked by characters’ text messages are often even more spacious and ethereal than the shots of the theme park. The play among all these spaces marks Jia as the most talented Asian director currently at work — with the possible exception of Hou Hsiao-hsien, whose hauntingly minimalist Cafe Lumiere will be playing at the Music Box in January.

2. Not on the Lips. At 35, Jia may be the youngest supreme film master working today. At 83, Alain Resnais is the second oldest working regularly, after 97- year-old Manoel de Oliveira, who visited Chicago for the first time during this year’s film fest. This exquisite film version of a 1925 operetta is Resnais’ fifth cinematic effort to convey his love of musicals, and in some ways it’s his most successful. A weird, ghostly farce about loneliness and emotional fragility, it’s also an anachronistic history lesson, with its 1920s manners, 1950s MGM colors and lighting, and early-21st-century French racism and anti-Americanism. It also displays much of the formal mastery of previous Resnais masterworks, including Last Year at Marienbad (1961), Providence (1977), and Melo (1986). Fox Lorber never bothered to advertise this film, but it’s been available on DVD since March, when it also screened at the Gene Siskel Film Center.

3. A History of Violence. I’ve yet to encounter a single attack on David Cronenberg’s multilayered yet fluid meditation on violence in George Bush’s America — filmed entirely in Canada. The writer-director clearly knows what he’s doing — note the brilliantly worked-out sex scenes — and though the film peaks well before its end, making the climax almost an afterthought, it’s less a serious flaw than an indication of how lean and mean the earlier segments are.

4. Ten Skies. Here’s an experimental film seen by many fewer people than the titles above, having screened only once at Chicago Filmmakers. This masterpiece by James Benning is an elaborately constructed montage of ten ten-minute takes, a mesmerizing study of time, light, movement, and moisture that traces the shifting relations between clouds and earth, nature and people. It had much more to say to me than most narrative films, though the subtly shifting patterns and textures of each shot provide plenty of narrative as they tell the story of our own perceptions.

5. Tropical Malady. All three features to date by Thai writer-director (and School of the Art Institute of Chicago graduate) Apichatpong Weerasethakul confirm that he’s one of the most creative and unpredictable film artists now working anywhere. Each time out he becomes more ambitious, though Mysterious Object at Noon and Blissfully Yours were hardly modest efforts. Part one of Tropical Malady shows the budding romance between a soldier on leave and a shy country boy with a mixture of irony and tenderness. Part two turns folkloric and allegorical as the soldier travels through a dark forest, alternately stalking and being stalked by his lover in the form of a tiger spirit, with a talking baboon offering sage advice.

6. A tie between two kids’ movies, Howl’s Moving Castle and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, both based on well-known English novels. I especially value the first, Hayao Miyazaki’s animated feature—based on Diana Wynne Jones’s book and the most commercially successful domestic release in the history of Japanese cinema — for the radical fluidity with which people and objects undergo constant transformation and for the implied philosophical position: that wisdom doesn’t so much succeed callowness as peacefully coexist with it. The same can be said for dreams and waking reality. The triumph of Tim Burton’s delirious riff on Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is more in the surrealist design and nightmarish dislocation than in some metaphysics. The off-putting aggressive mannerisms of Johnny Depp as chocolate tycoon Willy Wonka are a reminder that Burton has better instincts for the visual than for human behavior.

7. A tie between two literary movies, Yes and Capote, both highly unexpected successes. Yes, a post-9/11 love story about an Irish- American scientist (Joan Allen) and a Lebanese surgeon working as a cook (Simon Abkarian), proved that contemporary world politics could be gracefully confronted in iambic pentameter. It’s the best film Sally Potter’s made since The Gold Diggers (1983), in part because she found something affirmative to say. Capote showed that Truman Capote’s downfall could be partly explained by the ethical and emotional conflicts he went through while writing In Cold Blood. It had the advantages of a first-rate actor (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a highly focused script by Dan Futterman, and the economical direction of Bennett Miller.

8. A tie between two up-to-date works about art by old masters, Michelangelo Antonioni’s 17- minute Michelangelo Eye to Eye (2004) and Ingmar Bergman’s feature-length Saraband (2003). Michelangelo Eye to Eye, shown in 35-millimeter as part of the Onion City Film Festival at Chicago Filmmakers, used digital technology to show Antonioni, now in his 90s and confined to a wheelchair since 1985, walking through Saint Peter’s in Rome, looking at and caressing Michelangelo’s restored Moses — one restored Michelangelo considering another. Saraband, a sequel to Bergman’s 1973 Scenes From a Marriage, was shot in DV and shown that way at Bergman’s insistence during its commercial release. It’s a kind of postcinematic effort by Bergman, now in his 80s, made with a new technology after a 60-odd-year career using film. The content is typically self-punishing, but I could only admire his willingness to record such barrenness using a technology that wouldn’t grant it even a modicum of glamour.

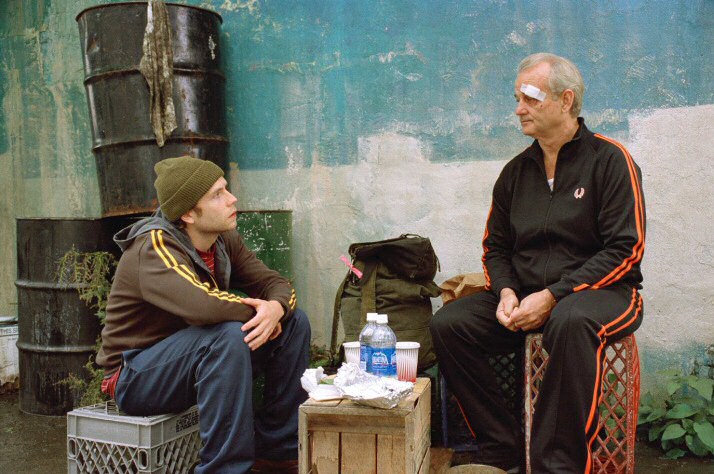

9. A tie between two plaintive comedies about lonely fuckups, Jim Jarmusch’s Broken Flowers and Miranda July’s Me and You and Everyone We Know. I could have made this a three-way tie and included Noah Baumbach’s The Squid and the Whale, but once the shock of it wore off I didn’t find its negativity as clarifying as I would have liked. Jarmusch’s feature lacks the formal and moral complexity of his underrated Coffee and Cigarettes, and the fact that he edited it backward is apparent, because it starts out rich and ends up depleted. Bill Murray’s narcissism bores me almost as much here as it did in Lost in Translation, but the other actors are delightful. July’s compulsion to tweak Americans for their puritanism is also somewhat off-putting, but the characters are sweet, her direction deft.

10. A tie between two examples of not-quite science fiction, Hal Hartley’s modest The Girl From Monday and Wong Kar-wai’s almost Wagnerian 2046. Hartley’s hilarious futuristic satire imagines a “dictatorship of the consumer,” with citizens wearing bar codes on their wrists and regarded as “investments with growth potential,” especially when they have sex. Wong’s first film in ’Scope, a labyrinth of longing, begins in the last year of Hong Kong’s economic and political independence but is set mainly in the 60s and concerns his parents’ generation.

Sad to say, none of the documentaries I saw about the war in Iraq seemed adequate to the subject. They all seemed too “embedded,” too timid, too dependent on cross-referencing Hollywood fantasies like Apocalypse Now. It’s obviously important for Gunner Palace to show that some innocent families in Baghdad whose houses were ransacked for weapons got sent to Abu Ghraib even though no weapons were found, but it’s offensive to treat such information as incidental and secondary. Ironically, Joe Dante’s crude, fictional Homecoming — an angry satire about slain soldiers returning from their graves to vote the president out of office, which turned up on Showtime’s “Masters of Horror ”— came closer to bearing witness to the war’s true meaning.

Far too much fuss has been made lately about liberal-minded fiction films that make liberalminded viewers feel sensitive and virtuous. As a first feature, Paul Haggis’s Crash certainly has its high points, but fresh insights into the nature and ramifications of racism aren’t among them, and the complacent Altman- esque ironies don’t help. (Curiously, Jan Hrebejk’s uncannily similar and equally accomplished Czech film Up and Down was ignored by critics.) I was moved by both Brokeback Mountain and Rent, but they still seemed overly contained. Steven Spielberg may have learned to think beyond Zionist reflexes, but Munich, like Raiders of the Lost Ark, is still supposed to make us feel good about the slaughter of Arabs, though we’re now also supposed to feel bad about feeling good.

Ten other movies I liked, in alphabetical order: The Beat That My Heart Skipped; The Brothers Grimm; Fear and Trembling; Goodbye, Dragon Inn; Lord of War; Notre Musique; Or (My Treasure); Play; The Producers; and Safe Conduct.

My annual F.W. Murnau award, given to the film that did the most to alter my sense of film history, goes to the wonderful, radical 1966 Jacques Rivette documentary Jean Renoir, the Boss: A Portrait of Michel Simon by Jean Renoir, or A Portrait of Jean Renoir by Michel Simon, or The Direction of Actors: Dialogue. Unlike most of what I saw in 2005, it was blissfully free of compromise.