From Cineaste, Fall 1995. — J.R.

The Films of Vincente Minnelli

by James Naremore. Cambridge University Press, 1993. 202 pp, illus., Hardcover: $65.00. Paperback: $27.99.

The critical position of James Naremore is Frankfurt school auteurism, a seeming contradiction. That is, he shares the Marxist orientation of many Frankfurt school intellectuals but not their disdain for the artifacts of mass culture. (To be sure, not all Frankfurt school members can be characterized in quite so monolithic a fashion; see, for instance, the prewar journalism of Siegfried Kracauer published this year in The Mass Ornament.) As a consequence, Naremore’s work shows an interest in style and pleasure that runs against the puritanical grain of most American Marxists, without ever losing sight of the social and political issues avoided by most American auteurists.

This is an idiosyncratic and progressive book in a series, the Cambridge Film Classics, that has mainly been conformist and conservative, especially in relationship to non-American filmmakers. Its volumes always focus on a few “representative” features rather than complete oeuvres, and Naremore’s study of Minnelli focuses on Cabin in the Sky, Meet Me in St. Louis, Father of the Bride, The Bad and the Beautiful, and Lust for Life, but only after an Introduction and first chapter that take up a quarter of the book and lay a considerable amount of contextual groundwork. What emerges thus aspires to a certain suggestiveness about Minnelli’s work as a whole but not any sort of completeness.

In effect, Naremore organizes his entire study around the image of a shop window. He begins by citing Orson Welles’s 1945 review of Ivan the Terrible, which contrasted Soviet and Hollywood methods of filmmaking and described “the screen being filled” in the latter “as a window is dressed in a swank department store.” Naremore cites Minnelli as the “single filmmaker of the period who most exemplifies the ‘swank’ tendency [Welles] was describing,” and then goes on to note, ironically, that “Minnelli’s first professional employment, long before coming to Hollywood, was as a designer of display windows for the Marshall Field department store in Chicago,” a fact that he immediately links to aspects of two Minnelli features — the title Designing Woman and the “crisis that breaks out in a mental institution” in The Cobweb “when new drapes are selected for the common room.” And Naremore’s final chapter (“Vincente Meets Vincent”), which begins with a remark about the commodification of Van Gogh made in The Cobweb, virtually ends with the observation that when Lust for Life was released in New York, “a host of elegant department stores — Henri Bendel, Best and Company, Bonwit Teller, Lord & Taylor, Ohrbach’s, De Pinna, Franklin Simon, Jay Thorpe, and Gimbel’s — loaned MGM their windows for ‘the display of fashions against the backdrop of landscapes and still lifes painted by Van Gogh.'”

Within the terms of this book, in other words, the shop window becomes as relevant to Naremore’s cultural critique as the lenses of the camera and the film projector by serving as a vehicle transporting a style of art into a way of life. Throughout this study, he is concerned with Minnelli’s work as a complex and ambiguous response to modernism — a response entailing not only commodification but also diverse other forms of translation and transmutation whose social and artistic consequences have to be considered with some tact and delicacy rather than simply deplored or defended. (There are many value judgments made throughout this book, but none as categorical as the typical auteurist celebration or Marxist dismissal.) Naremore is interested in sketching out the ideologically charged battlefields where Minnelli’s films and their artistic and social allegiances intersect with the contemporary issues of “political correctness,” where questions of race, gender, sexuality, social class, and culture are repeatedly posed. For better and for worse, this tends to make his writing somewhat cautious as well as gracefully nuanced — the carefully wrought formulations of a writer walking on eggshells. But part of what makes this book so lively as criticism is its capacity to draw its arguments from many sources. It is formidably researched in terms of backstage information as well as previous Minnelli criticism; at one point, Naremore traces the same “white wicker chairs designed in a lacy, rococo filigree” from Cabin in the Sky to Meet Me in St. Louis to Two Weeks with Love, and he is every bit as attentive to French critics like Jean Douchet and Jean Domarchi as he is to English critics like Richard Dyer or Thomas Elsaesser — or to James Agee and Manny Farber in the U.S.

For Naremore, Minnelli’s “historical importance lies in his ability to modernize entertainment, drawing on both ‘high class’ and bohemian domains of art.” The author singles out Minnelli’s specific borrowings from art nouveau, impressionism, postimpressionism, and surrealism, but he is no less concerned with the appropriations of “urban Africanism” in Cabin in the Sky, the sympathetic handling of Midwestern women “as representatives of an emerging consumer society” in Meet Me in St. Louis, the elements of noir and “putting-on-a-show” musicals like The Band Wagon underlying the various anxieties (sexual as well as economic) in Father of the Bride, the appropriations and political reversals of Citizen Kane in The Bad and the Beautiful (with John Houseman perceived as the crucial link between the two films), and the critical handling of conventional notions of “hypermasculinity” in Lust for Life.

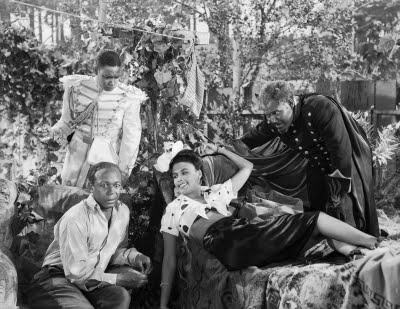

Naremore’s ambivalences about these films are all instructive. Cabin in the Sky — seen as “suburban rather than folkloric, because it blends MGM’s middle-class values with the Freed unit’s relatively elite Broadway ethos” — is “never free of racism,” yet at the same time its “transformation of blackness into a commodity on display has a salutary effect,” at once utopian and progressive, comprising “a step forward in the democratization of show business.” In Meet Me in St. Louis, “the world has become a theme park,” yet there is also some reason to believe that the Halloween bonfire, in the film’s most disturbing sequence, reminded 1944 audiences of Nazi book burnings.

After pointing out how Father of the Bride was specifically used to market a line of women’s clothing in 1950, Naremore offers a scathing appraisal of the recent Disney remake, whose multiple product plugs and ideological compromises make the original seem relatively innocent. Evoking the campy extravagance of a key moment in The Bad and the Beautiful, he notes how the “skin-tight, black velvet gown” of Elaine Stewart make “her breasts look like the bumpers of a fifties Cadillac,” and he is no less provocative in describing the schizophrenic effect of James Donald, the English actor playing Theo in Lust for Life, speaking all the off-screen quotations from Vincent’s letters on the soundtrack: “On the outside, Van Gogh looks clumsy and rather American; on the inside, he has the refined soul of a British Shakespearean actor.” In all these examples — and one could cite many others, such as the discussion of the deterioration of Lust for Life‘s original Agfacolor and the difficulty in seeing Minnelli’s CinemaScope features in their original formats today — Naremore’s feeling for ideological nuance becomes translated into a textual alertness and a sense of detail rarely encountered in academic film study. One emerges from this book with the same sense of renewal one would get from seeing a Minnelli film in a restored print.