This review appeared in the Spring 1979 issue of Film Quarterly (vol. XXXII, no. 3). Consider it Part 1 of a two-part consideration of Alan Rudolph, carried out over a span of a dozen years, to be followed by my much more ambivalent take on Mortal Thoughts (1991) for the Chicago Reader, which deals with some of the same issues involving both class and music. (I suspect that Rudolph’s best movie remains Choose Me, but I’d have to see this again to be sure.) — J.R.

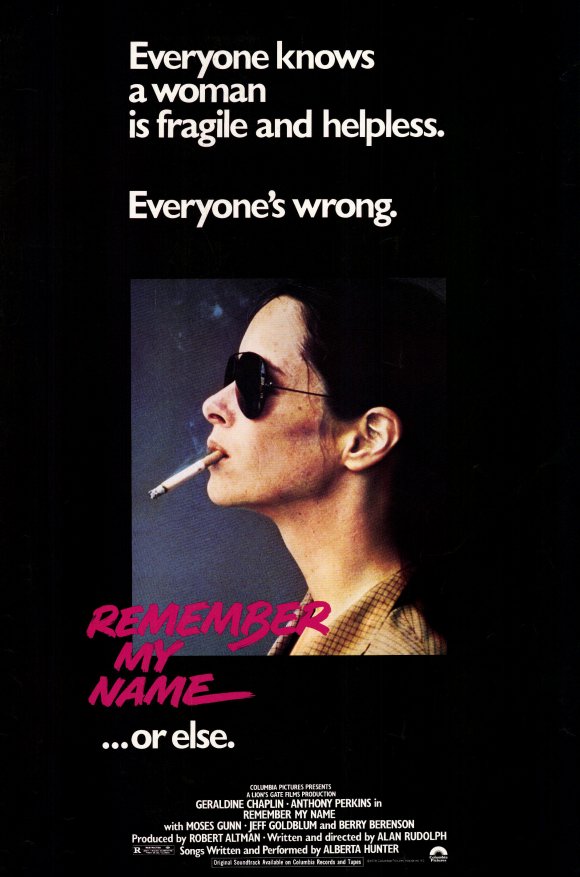

REMEMBER MY NAME

Director: Alan Rudolph. Script: Rudolph. Photography: Tak Fujimoto. Music: Alberta Hunter. Lagoon Films.

Alan Rudolph’s second film was financed by Columbia, then written off as a disaster before it was released, but it has been running successfully in Paris for months and opens shortly in New York. It strikes me as the most exciting Hollywood fantasy to come along in quite some time. Admittedly, I am a Rivette enthusiast; I am fascinated by narrative suspension and indeterminacy, and tend to lose interest when a plot is laid out in full view, because I’ve usually seen it before. Remember My Name deliberately suspends narrative clarity for the better part of its running time, and never entirely eliminates the ambiguities that keep it alive and unpredictable — even though its themes, thanks to Alberta Hunter’s offscreen blues songs, are never really in question. It will only confound spectators and critics who perceive movies chiefly through their plots.

A simple look at Rudolph’s plot shows it to be as sketchy, in narrative terms, as the blues written and sung by Hunter — and no less expedient and suggestive for his own purpose, which is to offer a concerto for Geraldine Chaplin. Rudolph has said that he wanted to do “an update on the themes of the classic woman’s melodramas of the Bette Davis, Barbara Stanwyck, Joan Crawford era”; one could also cite the Warner Brothers social protest films of the thirties as a useful reference point. Either way, the aim clearly isn’t to imitate the models or criticize them à la Movie Movie, but to use them the way a jazz musician uses chord changes -– as a launching pad, not a destination.

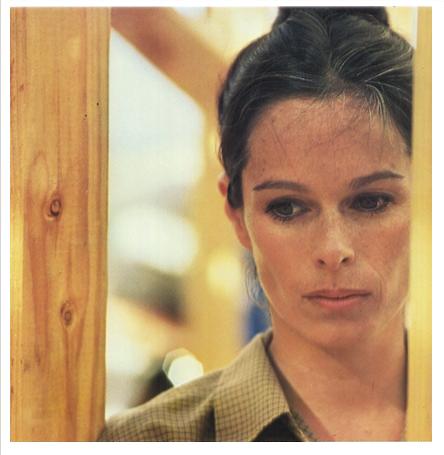

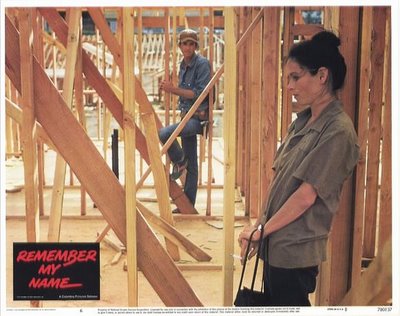

Newly emerged from twelve years in prison, Emily (Chaplin) drives into a town where Neil (Anthony Perkins) works as a hardhat, and starts bugging both him and his wife Barbara (Barry Berenson) for mysterious reasons: calling their home and then hanging up, driving past Neil on a construction job, yanking flowers out of their garden, and entering the house when Neil’s away to explore the rooms and confront Barbara in the kitchen (asking her, “Are you a good fuck?” and remarking that she met Neil “in the back of a crowded car” when he was twenty years old).

Meanwhile, Emily starts sleeping with her black landlord, Pike (Moses Gunn), in exchange for some domestic furnishings. Alone in her room, she rehearses a speech to Neil (“I didn’t cry when you disappeared…”) She argues her way into a job in Thrifty Mart, incurs the enmity of Rita (Alfre Woodward), a black coworker, assaults her, and stabs Rita’s boyfriend with a pencil when he comes on to her. Barbara, who witnesses this event by chance, has Emily arrested for smashing her window, forcing a confrontation between Neil and the two women in turn. Emily sees Neil at the police station and finally delivers her speech about her emotional and sexual obsession with him “over the past 4,380 days.” Neil convinces Barbara to drop charges, then confesses that he was once married to Emily, who went to prison for running over a woman he was having an affair with.

Appalled by this information, Barbara leaves him. Neil gets fired, phones Emily, meets her in a bar, gets drunk, and lets her make love to him. In the morning, Emily swipes his credit card to buy a new wardrobe before driving away, leaving Neil to face a resentful Pike.

The flimsiness and banality of such a fictional world – which asks us to accept Perkins as a shifty, no-account hardhat, and Chaplin as a rough equivalent to Toshiro Mifune in Yojimbo — is readily apparent. Rudolph uses a form of narrative striptease to keep his plot suspenseful, but this turns out to be partially a ruse; a fully legible and comprehensive fictional world isn’t what he’s after, as we see for example from the fact that he never definitively clarifies whether or not Emily steals money from the Thrifty Mart cash register.

Indeed, Emily’s “sincerity” is an ambiguous issue on one level or another in virtually every scene. No less duplicitous, ambivalent, and opaque than Ophüls’ Madame de…, she literally makes herself up as she goes, and the only proper way to respond to this challenge is to improvise along with her, assigning her a set of ephemeral, almost discontinuous identities while being strung along on Rudolph’s narrative and stylistic continuities. Thus while narrative exposition (including Emily’s separate actions), matching camera movements and repeated blues motifs, both singly and in concert, imply an unwavering singleness of purpose, the actual performance of Emily (and of Chaplin) proceeds like a series of bold experimental forays and flourishes around this obsession, a virtuoso “solo” that swirls through diverse possibilities while hitting all the octaves.

If one could take Emily apart the way Bulle Ogier takes apart the Russian doll in L’amour fou, one might find only a succession of deceptive layers stripped away to reveal a void — an empty center that the rest of the film defines. But in fact, the rest of the film asks us to put her together, out of the same fragments of her past that she is struggling to free herself from, so that we “fully” grasp her social identity at the same point that she puts it behind her — abandoning us along with Neil and Pike to make a fresh start.

Before this happens, she’s an outcast shopping for an identity, trying on everything that could conceivably fit. Her first and last stop in town in this very symmetrically designed movie is significantly at a clothes store, where she stakes out a wardrobe like a samurai choosing weapons. (This proves to be all that she needs; driving past a familiar poster — “Use a gun/Go to prison/That’s the law” — she can only smile.) Sufficiently armed, she stalks through the remainder of the film with as much pizazz as any Norman Mailer hero, using her eccentricities largely as diversions to throw her victims off balance.

Consider her approach to a recalcitrant Pike when she wants window drapes and clean sheets for her room. “I know what you want, you want me to beg for favors –- okay, I’ll beg.” She gets down on her knees in an abject parody of begging, hands outstretched: “Clean sheets? Clean sheets? Gimme clean sheets — drapes for my window…” Then she suddenly, violently leaps to her feet and cries, “Don’t you dare kiss me!”, slaps him, and falls into his arms, disarming him completely. “Takes a woman to take a man outa himself,” he mutters bemusedly — incidentally suggesting why Remember My Name qualifies as a male fantasy more than feminist tract. Then, to save himself a bit of honor, he adds: “But to do that she’s gotta be better than him.”

And she is: not only with Pike, but with every other man (and woman) she encounters, each of whom is gradually dismantled by her arsenal of discontinuous, seemingly contradictory moves. The psychological logic of this strategy is that her past and her obsession are wholly matters of monotony and stasis -– as fixed and rigid, in a way, as the traditional blues forms used by Hunter. And the only way that she (or we) can work though this limitation is to improvise on the given chords -–assuming diverse roles and stances in relation to the action while forging ahead in the existential present.

This is the first time I’ve ever wholly accepted Geraldine Chaplin in an American film — perhaps because it’s the first American film that’s been built around her unusual and inventive mannerist talents. Her role as Opal, the obnoxious groupie in Nashville, was obviously central to Altman’s conception, and was reportedly conceived of as a parody of his own role as director; yet his failure to develop this role beyond satirical platitudes while continuing to use her as an identification point for the spectator eventually revealed a certain hollowness at the center of that conception. (The part was distorted, too, in the final editing, leaving one with the impression that Opal was really supposed to be a BBC correspondent, not just a pathetic fraud pretending to be one.)

Annie Oakley in Buffalo Bill and the Indians offered Chaplin a more nuanced role and yielded a much subtler performance, but this wound up getting buried under the braggadocio of the male hamming that ultimately swamped the film. And as the reception co-ordinator in A Wedding, she was handed another satirical cutout like Opal to mimic.

It was Rudolph’s first (and previous) feature, Welcome to L.A., that probably gave Chaplin her first real chance to show her wares in an American context. (I’m unfamiliar with most of her work for her husband Carlos Saura, and have only the dimmest recollection of Dr. Zhivago; but in Rivette’s still unreleased Noroît, where she plays a solitary avenging pirate –- clearly anticipating her avenging ex-con in Remember My Name — her capacities as a mime, often evocative of her father’s, are allowed to function powerfully in a completely nonrealistic mode.) What she lacked was a strong enough conception to “place” her eccentric character and performance in a particular context. Richard Baskin’s narcissistically self-pitying and droning songs — establishing a thematic center that her secondary role was supposed to help illustrate – projected a charming (if unlikely) sort of self-conviction, but not enough to support and enhance a major performance. This is what the firmer and tighter strategies of Remember My Name generously provide.

Some residue of Robert Altman’s influence in a few off-center gags and motifs — a loony customer at the thrifty Mart; several TV news reports about a catastrophic earthquake in Budapest (which everyone ignores); a thematic preoccupation with dwelling units and locks — shouldn’t disguise the fact that Rudolph develops a much stronger independence from his producer’s style here than in Welcome. The audacity of teaming Chaplin with a black octogenarian blues singer in an audiovisual “duet” implies a stylistic discipline and concentration that is not apparent in Altman’s other recent productions, where notational gags and details claim most of the space –- crowding out the possibility of the kind of “star” performance that Chaplin gives here. Settling on a tight yet relaxed framework where the anger and passion of a wounded outsider can define its own awesome limits, Rudolph allows both women to wail, and the results are spellbinding.

— JONATHAN ROSENBAUM