Written for a Criterion rerelease, released in November 2020.. — J.R.

Along with Dead Man, his previous narrative feature, Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai marks a quantum leap in the Jim Jarmusch universe — a discovery of history (both antiquity and tradition) that carries with it a sense of gravity and even tragedy missing from his first five features. And paradoxically, along with his embrace of antiquity comes an uncanny intimation of the future from a 1999 perspective — an anticipation of social media and their mythical assemblies of identities and fanciful hashtags, a full decade before Facebook and Twitter rose to prominence, all the more surprising from a committed Luddite who would subsequently opt for faxes over email and post only on Instagram.

Jarmusch’s special way of evoking contemporary online individualities is a mix-and-match game of movie-genre tropes (including a final shoot-out scene), references to particular films (e.g., pigeons kept on a New Jersey rooftop, from On the Waterfront), and diverse literary touchstones ranging from The Wind in the Willows to Frankenstein. It also involves mythical profiles that sometimes merge with (or at least suggest) star presences, something Jarmusch has long depended upon, including his evocations (and invocations) of Elvis in Mystery Train (1989) and Nikola Tesla in Coffee and Cigarettes (2003), and his uses of, among many others, Roberto Benigni and Tom Waits in Down by Law (1986), Gena Rowlands and Winona Ryder in Night on Earth (1991), Johnny Depp and Gary Farmer in Dead Man (the latter of whom briefly returns in Ghost Dog), Forest Whitaker and Henry Silva in Ghost Dog, Cate Blanchett (in two roles) in Coffee and Cigarettes, and Isaach de Bankolé, Tilda Swinton, and Bill Murray in several films each.

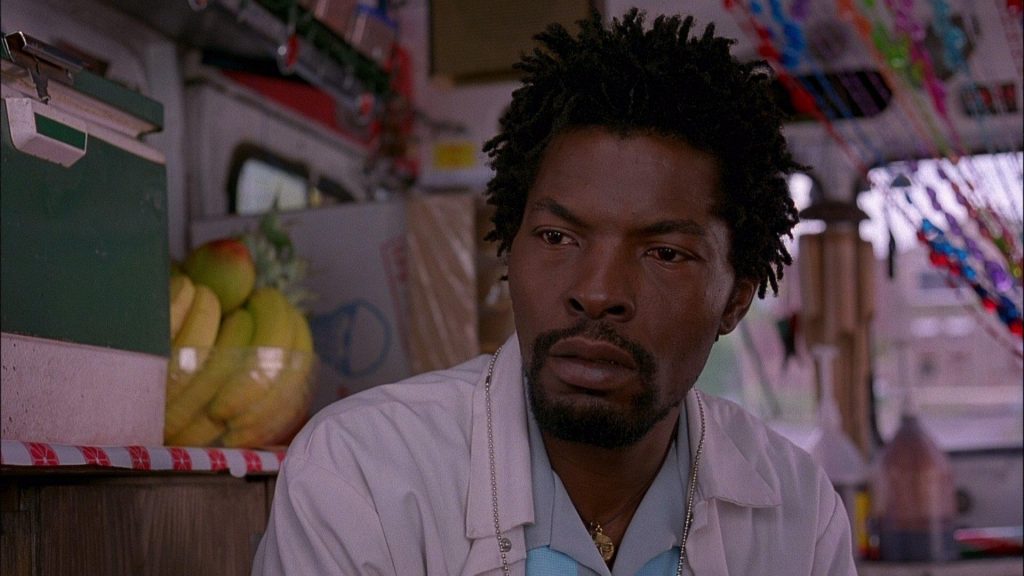

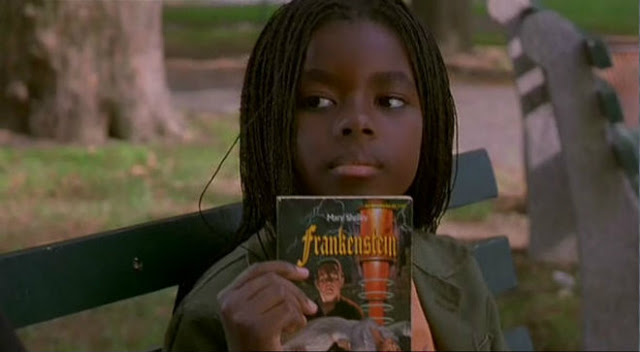

In Ghost Dog, the eponymous black hero (Forest Whitaker), whose life was once saved by Louie (John Tormey), an aging Italian American hoodlum, becomes Louie’s samurai hit man, communicating with him exclusively via homing pigeons while studiously applying the lessons of an eighteenth-century warrior text, Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai. Then, when something goes amiss during a hit, Louie’s gang decides to wipe out Ghost Dog, who retaliates in order to defend himself. Meanwhile, his friendships with a young black girl named Pearline (Camille Winbush) and a Haitian ice-cream vendor named Raymond (Isaach De Bankolé), both of whom he encounters in the same park, involve several other books—most notably, Mary Shelley’s nineteenth-century novel Frankenstein (“Even better than the movie,” says Pearline), Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s Rashomon and Other Stories (a collection of early-twentieth-century stories), and an undated French book about bears, which Raymond likes because for him it describes Ghost Dog, his best friend.

Neither Ghost Dog nor Raymond can speak or understand the other’s language, and if this sounds outlandish, it is no more or less so than Ghost Dog’s status as a samurai hit man or the use of those homing pigeons. If one wonders whether such premises are treated seriously by the movie or exploited for laughs as ridiculous, it is a sign of Jarmusch’s freedom and the audience’s own that the movie does both and never feels forced or out of step either way. The fact that it imparts so much tender and tragic dignity to its gangsters while keeping them both absurd and hilarious is linked to the same singular achievement.

The books that Ghost Dog discusses with Pearline are as important to the film as the quotations from William Blake’s poetry are to Dead Man, because, like Hagakure, they offer various kinds of life lessons and also because, in one way or another, they’re shared by two or more characters and thus become emblems of kinship or friendship. Moreover—with the possible exception of the Akutagawa collection, which circulates the most—the books cited above can be regarded as books about Ghost Dog. Indeed, Hagakure serves as his Holy Book and is quoted in the film in extended intertitles no less than thirteen times; the first dozen of these passages are read aloud and offscreen by Ghost Dog, and the final passage is read aloud by Pearline, suggesting that she becomes his spiritual heir.

Some viewers might become impatient with all these quotations, and there’s no question that each of them stops the story dead in its tracks —paradoxically, at the same time that it offers interpretive commentary about what’s going on at that point. But Jarmusch, having studied poetry in college and believing, as F. Scott Fitzgerald put it, that “action is character,” has never been overly concerned with his plots. These quotes from Hagakure call to mind a 1940s fantasy tale by Lewis Padgett (the pen name used by married writers Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore for their collaborations), “Compliments of the Author,” about a magical fifty-page book that offers all-purpose instructions to its owner about how to resolve various dilemmas — e.g., “Werewolves can’t climb oak trees,” “He’s bluffing,” “Try the windshield,” “Deny everything,” “Aim at his eye”; the relevant page number appears on the cover each time the book is needed, a total of ten times per owner. (Needless to say, the fiftieth page and last directive is “The End,” which echoes the final quotation from Hagakure in Ghost Dog: “The end is important in all things.”)

The thirteen Hagakure quotations offered over the course of Ghost Dog suggest a similar metaphysical conceit — meeting a desire for discipline and purity, a need to reduce uncertainty by limiting all understanding to a single book outlining a single way of life, a sort of primer that might also be seen as reflecting Jarmusch’s own long-standing embrace of minimalism.

Forming a dialectic with this volume is the Akutagawa collection, the opening story of which, “In a Grove,” consists of multiple contradictory accounts of the same incident, told from the viewpoints of separate characters. This story formed the basis of Akira Kurosawa’s famous film Rashomon; confusingly, the collection’s second story, “Rashomon,” furnished the basis for the same movie’s sentimental framing device. The philosophically radical message of “In a Grove” is that all the versions given of the same story are true; the more reductive message of Kurosawa’s framing story is that everyone lies, implying that all the versions given are false. Roughly speaking, Hagakure corresponds to Jarmusch’s background as a minimalist, and “In a Grove”—which suggests a multiple understanding of reality, something closer to cubism—introduces the more skeptical perspectives raised by historical speculation. Significantly, the movie stresses that the favorite story of both Pearline and Ghost Dog is “In a Grove” and not “Rashomon,” suggesting that even Jarmusch’s minimalism has its limits.

In Ghost Dog, the formal equivalent of this vision of multiplicity is a technique used in varying forms throughout the film: the lap dissolve, the means by which two or more separate images gradually overlap. Jarmusch, whose use of lap dissolves is much more extensive in Ghost Dog than in any of his previous films, employs them here in two distinct ways: to combine different subjects within the same shot (such as a slow pan across a city street at night and a fixed close-up of Ghost Dog) or to break up an action or moment into several instants (such as several different angles on a parked car that Ghost Dog is approaching, or several successive stages in his progress as he walks down the street). Both procedures, carried out with real distinction in Robby Müller’s glowing cinematography, correspond with some of the sampling techniques used by disc jockeys, and at times they also correspond to some of the other cultural mixtures Jarmusch is playing with. (By contrast, one lovely extended take, which shows Ghost Dog stealing a red convertible at night while its owner steps inside a liquor store, rivals the simplicity and purity of Hagakure.) The overall process of mixing and matching evokes Jarmusch’s background as a musician and is also reflected in RZA’s layered, hypnotic, and eclectic score.

***

From the start of his career, Jarmusch has been traversing the still barely discovered territory of global culture. He’s not simply or exclusively an “American independent” but an astute connoisseur of cultural essentials that tend to escape boundaries of nationality, ethnicity, language, gender, and age, and he’s broaching a realm of experience and potential bonding that’s daily becoming more important to the quality of our everyday lives on the planet. Considering the fact that the bird in flight behind the credits of Ghost Dog claims no nationality, why should we? If nothing else, wherever we happen to be living and whatever language we speak, most of us are affected by the propaganda and manufactured upheavals of the same multicorporate conglomerates controlling our environment — which arguably makes the whole world kin more than what we know as “communism” or “democracy” ever did, or could. This is how and why Jarmusch’s multicultural viewpoint could be shared by someone like the late Abbas Kiarostami, who accompanied his very first film, Bread and Alley (1970), with Paul Desmond playing a Beatles song, and would later use Vivaldi and Louis Armstrong over Iranian landscapes with an equal lack of self-consciousness. Similarly, Olivier Assayas’s Irma Vep — made three years ahead of Ghost Dog, with Maggie Cheung as herself playing a French thief in a remake of a silent serial — may have more to say about what North America, Hong Kong, and France have in common than about what makes them culturally disparate. Thanks to all our digital options, we basically are what we can share. So who we are is an essential part of what contemporary art can teach us, and over two decades after its release, Ghost Dog remains one of the most contemporary films that we have.

From the standpoint of today, given the elastic anonymity and community proliferation that define so much of cyberspace — only one of several contemporary arenas where nationality seems an increasingly outdated and antiquated mode of identification — it no longer seems ao far-fetched that a young black man might reinvent himself as an ancient Japanese warrior (one premise of Ghost Dog), that a small-time Italian American crook and a black samurai might be “almost extinct” members of “different ancient tribes” who treat each other with reciprocal respect (another premise), that a black American samurai and a black Haitian ice-cream vendor each unfamiliar with the other’s language can be best friends and communicate without any difficulty (still another), or that a slim paperback of Japanese stories might be passed along with profit from a white mobster’s daughter (Tricia Vessey) to the black samurai who rubs out her companion to a black girl whom he meets on a park bench and then back to the daughter again.

It’s worth adding that computers don’t figure at all in Ghost Dog, a movie whose sense of high tech is basically restricted to cars with fancy CD players, guns with silencers, and animated cartoons on TV (exploited for various thematic rhyme effects), and whose sense of antiquity is inseparable from its feeling for the present cultural moment. The point is that all the movie’s characters are casually liberated and even defined by their everyday capacity to drift between cultures: one of the aging white gangsters (Cliff Gorman) loves rap and chants along with it, and another (Henry Silva) responds to an enigmatic quotation about beheading from Hagakure by saying, “It’s poetry — the poetry of war.” For that matter, the same gang uses a Chinese restaurant for its clubhouse, although it’s far behind in paying rent.

For all the differences among Jarmusch, Kiarostami, and Assayas in relation to global culture, all three are easily misunderstood practitioners of DJ-like sampling, with all its possibilities and limitations. One can’t simply call global culture “good” or “bad” at this point in history because it mixes together too many potential pluses and minuses — broadening the reach and meaning of traditions and at the same time flattening them, often to the point where one has to redefine them. How and why Frankenstein’s “monster” or a bear might resemble Ghost Dog is a question (not an answer) that we’re invited to ponder along with the film’s characters.

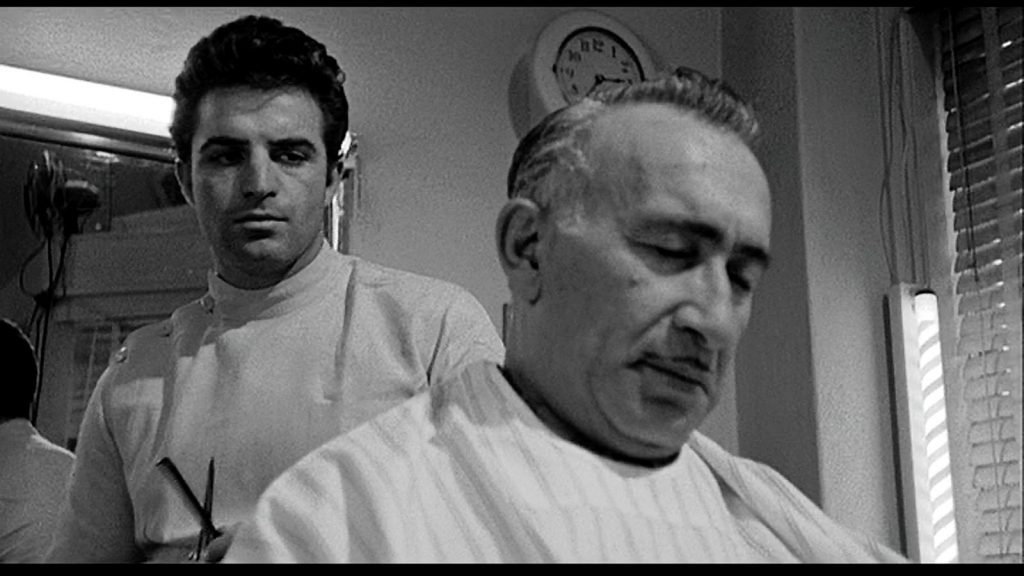

The functioning of a film or book or piece of music within global culture can’t be equated with its function as a piece of provincial, national, or folk art. Ghost Dog enjoyed successful runs in Japan and France, which might be partially explained by Jarmusch’s assurance in mixing and matching what he takes from the arty genre movies of both countries — in this case, from two very stylishly mannerist 1967 features, Seijun Suzuki’s Branded to Kill and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le samouraï —without ever compromising his own, equally mannerist artistic identity. (Irving Lerner’s minimalist 1958 noir and Zen thriller, Murder by Contract, a low-budget Hollywood effort, also seems quite relevant to what Ghost Dog is doing.) Jarmusch made a point of showing Ghost Dog to the once-prolific, then-unemployed, seventy-seven-year-old B-film maestro Suzuki, who responded, “I see you’ve taken some things from me, and when I make my next film, I’m going to take some things from you.” I’m still trying to figure out how fully this promise was carried out in Suzuki’s splendidly extravagant and immensely pleasurable Pistol Opera (2001)—a belated sequel of sorts to Branded to Kill— but the diverse uses of a wise young girl and an American character named Dr. Painless are particularly suggestive of an exchange between these two prescient global filmmakers, who, like Ghost Dog and Raymond, each didn’t speak a word of the other’s language.

This piece was adapted from a review originally published in the Chicago Reader on March 17, 2000.

Jonathan Rosenbaum’s books include Cinematic Encounters: Interviews and Dialogues (2018) and Cinematic Encounters 2: Portraits and Polemics (2019), both of which have chapters on Jarmusch, and Dead Man (2000).