This appeared in the June 11, 1993 issue of the Chicago Reader; I’ve also appended an irate response from a reader that appeared in a subsequent issue, along with my response. –J.R.

CLIFFHANGER

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Renny Harlin

Written by Michael France and Sylvester Stallone

With Sylvester Stallone, John Lithgow, Michael Rooker, Janine Turner, Rex Linn, Caroline Goodall, Leon, Paul Winfield, and Ralph Waite.

Kitsch is the daily art of our time, as the vase or the hymn was for earlier generations. For the sensibility it has that arbitrariness and importance which works take on when they are no longer noticeable elements of the environment. In America kitsch is Nature. The Rocky Mountains have resembled fake art for a century.

There is no counterconcept to kitsch. Its antagonist is not an idea but reality. To do away with kitsch it is necessary to change the landscape, as it was necessary to change the landscape of Sardinia in order to get rid of the malarial mosquito. –Harold Rosenberg, The Tradition of the New (1959)

Cliffhanger #1 (rating: four stars): Towering mountain ranges, yawning chasms, awesome expanses of stony matter, endless reaches of empty space, daunting inclines, imposing immensities that cause your jaw to drop and freeze into a painful rictus. The sound of helicopters and birds from the back as well as the front and side Dolby speakers add to your sense of measureless spaces, especially if the theater has a large auditorium. (I’d recommend McClurg Court, where I saw the preview.)

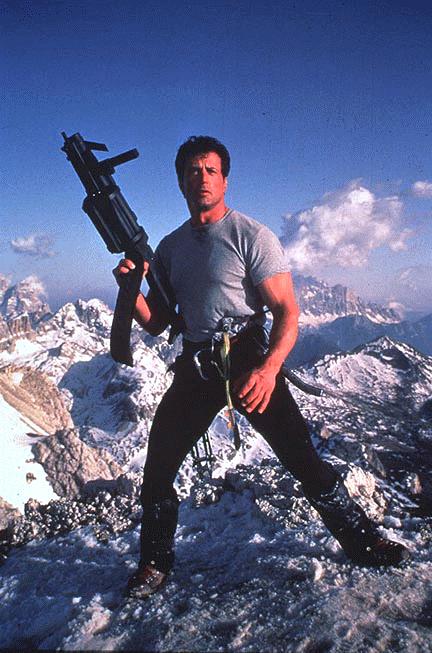

The smallness of human figures within this Olympian landscape takes some getting used to, especially for viewers who suffer from vertigo or agoraphobia. Yet the commanding, hulking, Nietzschean-superman physique of Sylvester Stallone as master mountain scaler in a series of superbly realized action and suspense set pieces makes him a worthy hero in such a setting — at least if anyone short of Zeus or Arnold Schwarzenegger can assume this mythical function. Women too play significant roles in this landscape — two as martyrs, a third as a bargaining chip between the master hero (Stallone) and master villain (John Lithgow).

The sacrificial roles played by women in this landscape — as well as the German-romantic grandeur of the landscape itself — immediately call to mind The Blue Light (1932), the first feature of Leni Riefenstahl, who became the Nazis’ major artist. A fairy tale with moral overtones much like The Blue Light, with a comparable indifference to everyday plausibility, Cliffhanger also displays similar ideological mechanisms, at least as spelled out by film historian and critic Eric Rentschler. He sees a “triad” at work in the Riefenstahl film that “functions as a central dynamic in Nazi fantasy productions,” consisting of what he calls “the elemental, the ornamental, and the instrumental.” The elemental refers to nature, while the ornamental points to a desire to see nature as art; the instrumental — less generally recognized — points to the maximized use of human beings within this aestheticized landscape, including certain sacrificial roles. For Rentschler, instrumentality culminated in German fascism’s “material domination over nature through a vast technology that stretched from the rationalized way in which an entire country was organized to an elaborate bureaucratic mechanism to a military machine, a world war, and ultimately the death camps, vast factories that recycled human bodies, pressing out of them every possible material gain before disposing of them. No doubt, the film industry played a central role in this machinery.” Although materialism is associated with evil in both The Blue Light and Cliffhanger and both movies can be said to appeal to what Rentschler calls “a romantic anticapitalism fueled by a discontent with contemporary civilization,” only the new film can be said to solicit pleasure from brutality.

Cliffhanger #2 (rating: no stars): High above the Dolomite Alps — where all of The Blue Light is set and most of Cliffhanger was filmed, though the main setting of Cliffhanger is supposed to be the Rocky Mountains — an evil band of international hijackers led by Qualen (Lithgow) and his mistress (Caroline Goodall), both English, are stealing $100 million in fresh bills from a U.S. Treasury Department cargo jet supposedly traveling from Denver to San Francisco. They’re accomplishing this task in midair, with most of the crooks waiting in another plane. A federal agent (Rex Linn) in their employ brutally kills everyone on board the cargo jet and transfers the three suitcases containing the bills to the hijackers’ plane. But due to a series of dovetailing mishaps, the suitcases fall into the mountains below, and the hijackers’ plane is forced to crash-land in the same area in the middle of a blizzard.

Using their radio they call the Rocky Mountain Rescue Team, which includes Jessie (Janine Turner), a helicopter pilot, and Hal (Michael Rooker), a mountain climber. Gabe (Stallone), an ace climber, quit his job as a member of the team almost a year before, after failing to save the life of Hal’s girlfriend, who was trapped with Hal on a mountaintop — the film’s spectacular opening sequence. Gabe tries without success to get Jessie, his own girlfriend, to leave the mountains with him, and is then shamed into joining the new rescue mission.

As soon as Gabe and Hal, who hates Gabe for the death of his girlfriend, reach the hijackers, they’re ordered at gunpoint to use their skills to retrieve the three suitcases. Their commands are given in as demeaning a manner as possible: “I want this dog on a leash. . . . Go fetch, Wonderdog.” It’s also clear that Gabe and Hal will be killed as soon as the money is recovered; for this bunch of thugs “instrumentality,” as Rentschler describes it, is a veritable way of life. We’re frequently asked to laugh at their meanness, and they show every sign of being able to share the amusement. “You want to kill me, don’t you?” Qualen says to Hal at one point. “Take a number and get in line.” A little earlier he waxes philosophical: “Kill a few people and they call you a murderer. Kill a million and they call you a conqueror. Go figure.”

In the many skirmishes between villains and members of the rescue team (which eventually includes Jessie and a male pilot), the nastiness and sadistic cruelty of the hijackers and their cheerful willingness to kill anyone who stands in their path are not only emphasized but celebrated — given diverse lyrical, poetic, humorous, and musical forms. Two separate machine-gun executions of innocent characters we’re encouraged to like are rendered like tone poems, without sound (except for music) and in slow motion. Qualen calmly and happily dispatches his own lover just after telling her, “You know what real love is? Sacrifice.” One villain delights in torturing Hal with successive kicks and slugs — all accompanied by the sort of patter that goes with a football game. (Like the ear-cutting showstopper in Reservoir Dogs, choreographed to a 70s pop song, this seems designed to make us say, “Far fucking out.”) Another villain, this one black, is impaled on a stalactite by Gabe. This list of aestheticized physical abuses is far from exhaustive, and the main point to be made about all this ecstatic violence is that it’s rendered as lovingly as the spectacular mountain vistas and Stallone’s comic-book physique — maybe more so, given the additional expressive and affective possibilities of dialogue and Dolby sound effects, which allow us to savor the full impact of every body blow, broken bone, and gunshot.

None of this, I should stress, has anything to do with the action of The Blue Light or any of Riefenstahl’s subsequent features, though it does suggest the kind of thuggery, sadism, and murder that was sanctioned and carried out by the Nazis — and that Riefenstahl was at pains to screen out in the interests of “pure,” ethereal art. The savagery here is sanctioned by another kind of institutional instrumentality, the Hollywood blockbuster; what it mainly shares with Nazi butchery is the satisfaction powerless and frustrated people gain from watching fantasies of conquest, domination, and retribution played out at length. The fact that their frustrations stem largely from the brutalities of capitalism is reflected in both the greed of the villains and the good guys’ indifference to money. But paradoxically the only kind of capitalism the movie wants to stand against is international hijacking. When it comes to the debasement of human life for the sake of profit, the film’s values are worse than those of the villains. The presumed appetite of the audience is simply for cruelty without even material profit, a desire the filmmakers are willing to exploit to the utmost.

Sometimes the film doesn’t even require the alibi of villainy to get the audience worked up, as when Gabe and Jessie are attacked by a caveful of bats. A man sitting in front of me at the preview was already cheering in the first sequence when Hal’s hapless girlfriend dropped screaming to her death — a moment that delighted him almost as much as Qualen shooting his lover after delivering his pithy one-liner.

The fantasies of the Nazis were of course played out in the real world, while the fantasies of Cliffhanger remain imaginary. Moreover, they’re imaginary events inflected by the ludicrous rules of political correctness that now inform many such entertainments, so that black men and white women are carefully cast as good guys and bad guys. Nevertheless many American fantasies of conquest, domination, and retribution — fantasies stimulated and nurtured by movies like Cliffhanger — are also carried out in the real world, where men and women, blacks and whites, are all allowed the pleasure of cheering the deaths of innocent Panamanians and Iraqis — and anyone else thought to stand in the way of what are whimsically referred to as American interests.

The degree to which movies that brutalize our sensibilities make such attitudes easier to contemplate, even easier to enjoy, can be debated, but it seems myopic to argue that there’s no relationship at all. It’s equally shortsighted to assume that the encouragement and exploitation of such attitudes in movies is necessary for an audience’s enjoyment. They certainly aren’t present in anything like this degree in Jackie Chan’s action romps or Douglas Fairbanks’s swashbucklers (Chan and Fairbanks also perform most of their death-defying stunts, unlike Stallone). The fact that we’re supposed to be awed by the cruelty as well as the stunts and the scenery is a specialty of contemporary Hollywood kitsch, and I think it tells us something about who we are.

Who are we, in fact? (According to Stallone, who collaborated on the script, this is a movie about “redemption.”)

Cliffhanger #1 would appear to be associated with the good guys and Cliffhanger #2 with the bad guys. I guess assigning most of the atrocities to villains is supposed to make the film all harmless fun. In any case, in trying to come up with a rating that strikes an average between the two movies I’ve arrived at two stars, which says that Cliffhanger is “worth seeing.” Is it? I found it an exciting and beautifully crafted piece of entertainment so barbaric that the civilization that produced it probably doesn’t deserve to survive, much less prevail.

***

To the editors:

I have to laugh at Jonathan Rosenbaum’s self-righteous, melodramatic, even hypocritical review of Cliffhanger [June 11].

I can sympathize with being anti-film violence; many people can and are (although I don’t really care myself). But in summing up, in both his full-length and capsule reviews of the film, he states that the film is “so barbaric that the civilization that produced it probably doesn’t deserve to survive, much less prevail.”

Such sophomoric earnestness. First, Jonathan as judge and jury deciding on the survival of Western civilization is a notion so barbaric, I can only beg: Mercy, Jonathan, spare us!!

Spare us, that is, your “ideas” on who should or shouldn’t survive, and stick to reviewing films. As for the evil nature of violent films, your simplistic viewpoint dilutes your thesis. There is a universe of difference between the vicarious thrill of watching what is thoroughly understood to be fake violence and cheering for the genuine article. (There may be those few barnyard animals who can’t tell the difference, and who want to practice for real what they see onscreen; they are an insignificant minority, and are completely beside the point.) The point is that the people who gawk and cheer do so for a sense of retribution and poetic justice, knowing full well it’s all in fun. These very same people would be struck dumb with horror if they knew this film were a covertly captured record of actual barbarism, because they are not barbarians; only the tiniest portion of our society fits that description. Be thankful that normal people don’t cheer when they witness real violence, Jonathan; then you’d have something to whine about.

Finally, your remark in the capsule review that the Persian gulf war was “savagery . . . celebrated . . . shamelessly . . . disgustingly” is preposterous, defaming your country, and flying in the face of about 90 percent of the nation at the time. My advice, again, is to stick to the knitting: Keep your politics out of your reviews; it’ll destroy your credibility.

David M. Marks

Evanston

Jonathan Rosenbaum replies:

The actual phrase that David Marks finds preposterous is, “except for our recent turkey shoots in Panama and the Persian Gulf, savagery is seldom celebrated as shamelessly or as disgustingly.” Since he pointedly leaves out Panama, I take heart in the possibility that he doesn’t regard the wholesale slaughter of thousands of innocent Panamanian women and children as an innocent, good-natured turkey shoot — unlike, apparently, the slaughter of thousands of innocent Iraqi women and children. I guess one way it becomes possible to celebrate and cheer such events is to keep politics out of movie reviews — which helps to explain how those CNN movies “Operation Desert Storm” and “War in the Gulf” could offer some Americans so much pleasurable entertainment without their fun being spoiled. “Be thankful that normal people don’t cheer when they witness real violence,” says David Marks. Does that mean that the fall of “smart bombs” on Iraq wasn’t real violence, or does it mean, rather, that the people I saw cheering them weren’t normal?