Written in March 2011 for Madman Entertainment, an Australian DVD company.

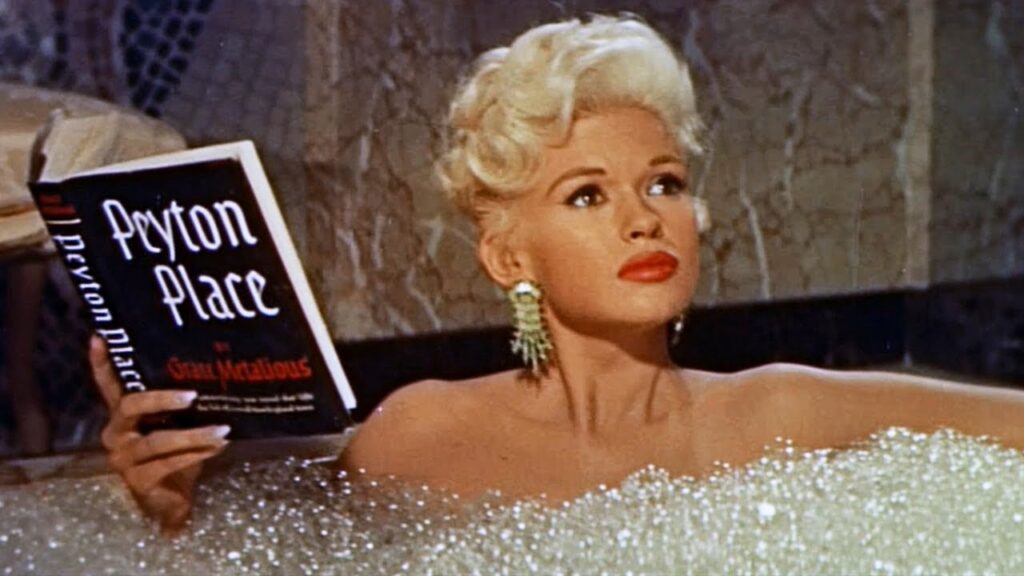

One couldn’t say that there’s any firm consensus that Frank Tashlin’s dazzling 1957 satire about advertising and television is his greatest film. Some Tashlin fans would opt for either of the two late Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis vehicles that he directed for Paramount, Artists and Models (1955) or Hollywood or Bust (1956), or else would select his earlier CinemaScope vehicle for Jayne Mansfield at Twentieth Century-Fox, The Girl Can’t Help It (1956). But there’s certainly no doubt that Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? stands apart from the rest of his work, as the freest and the most deconstructive of all his comedies — and it’s worth adding that Tashlin himself cited it to Peter Bogdanovich (who interviewed him in 1962, during the shooting of It’$ Only Money) as the film he was “most satisfied with”. (In another interview, he suggested that The Girl Can’t Help It was his other personal favorite; it appears that the role played by executive producer Buddy Adler in granting Tashlin an unusual amount of freedom and leeway on both pictures had a lot to do with these judgments.) In keeping with George S. Kaufman’s maxim that “satire is what closes on Saturday night,” Rock Hunter flopped at the box office and was disastrous for Tashlin’s career. But to paraphrase Roberto Rossellini, both it and Charlie Chaplin’s A King in New York, released the same year, are the films of free men.

Speaking personally, I regard it as his masterpiece. When I first encountered Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? in my early teens, it was the first movie I ever voluntarily sat through two times in a row, without leaving my seat. As a devotee of Mad when it was still a highly transgressive comic book in the early 1950s, before it became a magazine, as well as other parodic and satirical forms of cultural assault from that period ranging from the ephemeral (Sam Newfield’s 1951 Western Skipalong Rosenbloom, aka Square Shooter) to the deliriously mainstream (the raucous concert and recorded music of Spike Jones), I was certainly primed for its brand of reckless and irreverent humor.

But I was confused at the time about who deserved the credit for all its brilliance. Even though the credited producer, director, and writer was Tashlin, another title card clearly read, “Based on the Play written by George Axelrod and Produced by Jule Styne”. And the Axelrod play — which opened at the Belasco Theatre in New York on October 13, 1955 and ran for 444 performances –- was staged by Axelrod himself, who had also cast Jayne Mansfield as his female lead, Rita Marlowe, playing (more or less) the same character that she plays in the film. “As a matter of fact,” Axelrod said to Patrick McGilligan in an interview (Backstory 3: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1960s, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), “I directed [Jayne Mansfield’s] first screen test, and sold her contract to 20th [Century-Fox].” But in the same interview, he also maintained, “I never knew Frank Tashlin. I never worked with him. I had nothing to do with the film of Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? I never saw the movie. Not to this day….They didn’t use my story, my play, or my script [which implies that Axelrod wrote a never-used screenplay of his own]….I know what they did. I made it about the movies — they made it about television….Why do I want to torture myself by seeing it?”

Despite — or maybe because of — Axelrod’s tenuous and contentious connection with the film, it’s worth comparing his vision to that of Tashlin in some detail. Both are quintessential, era-defining figures of the 1950s, and both were satirists of the period’s pop culture and its crazed notions of hyperbolic sexuality who were widely criticized for being implicated in the targets of their satire. Both men, one might add, specialized in personal in-jokes as well as wimpy heroes whose masculinity is often challenged by the cultures they live in.

Yet in other respects, one could argue that these two men were diametrically opposed to one another in their views of humanity in general and American culture in particular. The world of Tashlin is essentially one without malice or evil or villains — a striking trait that he shares with director Joe Dante, his artistic heir in many respects — in which the culture they inhabit is skewered from top to bottom but not the people who live within that culture or even those who subscribe to its more ridiculous notions. One might therefore describe Tashlin as a social critic and a humanist but not as a misanthrope or a cynic. But Axelrod, far more metaphysical and unambiguously cynical and misanthropic, more typically depicts a godless universe that is literally ruled by the Devil.

His play Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? is in fact a variation on Faust, which accounts for the “Marlowe” in Rita Marlowe, but some of the same metaphysical traits crop up in Axelrod’s three novels (Beggar’s Choice, 1947; Blackmailer, 1952; Where Am I Now – When I Need Me?, 1971), his other Broadway plays (The Seven Year Itch, 1952; Goodbye Charlie, 1959), and, arguably, even many of his adapted screenplays (Bus Stop, 1956; Breakfast at Tiffany’s, 1961; The Manchurian Candidate, 1962; and Lord Love a Duck, 1966, which he also directed — the latter another variation on the Faust theme). A writer who specialized in the Walter Mittyish erotic fantasies of wimpy heroes, most of whom suffer from various rude challenges to their sense of their own masculinity (a characteristic that even carries over to the brainwashed mama’s boy played by Laurence Harvey in The Manchurian Candidate), he also played at times with literal gender switches: in his novel Beggar’s Choice, the writer hero gets hired out as a family cook while his wife becomes the family chauffeur, and his in play Goodbye Charlie, a Hollywood ladies man dies and gets reincarnated as a woman. The combination of these elements often recalls the earlier work of comic novelist Thorne Smith, whose source novels provided the basis for such films as Topper, Turnabout (a Hal Roach comedy about a gender shift between man and wife), and I Married a Witch.

It also seems pertinent that the bowdlerizing of and other changes in Axelrod’s first successful play, The Seven Year Itch, in the 1955 film adaptation that he wrote with director Billy Wilder, apparently soured Axelrod on movies in general and Hollywood in particular, which fed directly into the satire of his Rock Hunter. (“In addition to having a horrible Breen Office problem,” he told McGilligan — in reference to the Production Code dictating that the (wimpy) hero of the play, a married man, couldn’t have sex with his upstairs neighbor — “the play just didn’t adapt. The claustrophobic element of the play is what makes it work — a guy trapped in the little apartment, his imagination soaring out of the apartment. When you open the play up, it loses its tension.”)

There was a clear carryover from The Seven Year Itch (the play) to Rock Hunter (the play), and one that related to more than Jayne Mansfield offering a very broad parody of Marilyn Monroe, who had starred in the Wilder film. In Axelrod’s Rock Hunter, selling your soul to the Devil and moving from New York to Hollywood are viewed as mutually reinforcing propositions. Tom Ewell, who played the male lead in both the play of The Seven Year Itch and the film, wound up as the male lead in Tashlin’s The Girl Can’t Help It, and was originally set to play in the film of Rock Hunter, but a commitment to appear in a new play forced him to bow out at the last minute, and Tony Randall stepped into the part only two weeks before shooting started. (Another last-minute casting change involved the film’s surprise “guest” star — which was originally supposed to be Jerry Lewis, until Hal Wallis refused to release him from his contract at Paramount, at which point Lewis was replaced by Groucho Marx.) And other sea-changes in the project undoubtedly confirmed Axelrod’s demonizing of Hollywood from his own vantage point. Fox was clearly more interested in acquiring Jayne Mansfield (which caused her to drop out of the play in order to costar in The Girl Can’t Help It) than in acquiring Axelrod’s material, as Tashlin’s comprehensive rewrite demonstrated.

In Axelrod, one might also say that shifts in gender ultimately lead to shifts in genre — something that also could be said of Tashlin only if one regards cartoon animation and live-action as separate “genres”, because he started out working in Hollywood animation and eventually shifted many of its principles over to live-action slapstick gags. He uses this background in the molding of Rock Hunter’s stars — Tony Randall and Jayne Mansfield, both giving their best performances — into cartoons. Randall’s a nerdy Madison Avenue executive with rolling eyeballs, Mansfield’s a tall, squeaking, Betty Boop-ish movie star with cleavage. (In tribute to Randall, Tashlin said to Bogdanovich, “Oh, he’s great. Like a comic machine. You feel like [violin virtuoso Jascha] Heifetz when you work with him.”)

One way of distinguishing the confusing shifts between genres in The Manchurian Candidate (which Axelrod produced as well as scripted), including the dizzying oscillations between melodrama and comedy, from those in such contemporary French New Wave features as Breathless, Shoot the Piano Player, and Last Year at Marienbad, is that the French films were grounded in cinephilia, as were Tashlin’s comedies, while Axelrod’s contemporaneous film, for better and for worse, is grounded in cynical and Pavlovian button-pushing. (It’s worth recalling that Tashlin had a huge stylistic impact on the New Wave. Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? — which Jean-Luc Godard cited as his third favorite film of 1957, after Bitter Victory and The Wrong Man, and immediately before Hollywood or Bust — can be regarded as the template for Godard ’s bold use of primary colors and ‘Scope in such 60s films as A Woman is a Woman and Pierrot le Fou, and Artists and Models, about the 50s craze for comic books — starring four more Tashlin cartoons, Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis, Dorothy Malone, and Shirley MacLaine — was the acknowledged inspiration for Jacques Rivette’s 1974 Celine and Julie Go Boating.)

Hatred for the mass market — best sellers, Hollywood, advertising — is something close to a constant in Axelrod’s work. Given that Axelrod was himself entirely a creature of the mass-market, this invariably led to diverse forms of self-hatred, despite (or, again, perhaps because) of the fact that so many of his heroes were writers.

The world-view of Tashlin, by contrast, is decidedly sunnier. Finding American culture ridiculous isn’t necessarily or invariably equivalent to hating it; in Tashlin’s case, on the contrary, it becomes a means for appreciating it. The published version of Axelrod’s play of Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? —which was reportedly called Will Success Spoil Rock Hudson? before Hudson’s agent threatened a lawsuit — is prefaced by the words, “Ten percent of this play is dedicated to Irving Lazar,” and in fact the plot, which opens in Manhattan before shifting to Hollywood for the next two acts, describes the sale of the soul of the wimpy faux-hero George MacCauley (Orson Bean), a fan magazine writer with only one published article to his credit, to a Hollywood agent, Irving LaSalle (Martin Gabel), for successive ten percent increments, in exchange for fame, fortune, and the love of Rita Marlowe. (The “real” hero in the play, however, is a “real” writer — Michael Freeman, played on the stage by Walter Matthau — who resolves everything at the play’s end by getting George to accompany him back to “real” Manhattan, just in time for an earthy snowstorm, carrying along only his treasured typewriter as a prized possession.)

The one fan-magazine article written by George is in fact titled “Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?”, but no visible character in the play goes by that name. In his almost completely rewritten script, Tashlin essentially combines Michael and George into a Manhattan-based writer of TV commercials, Rockwell P. Hunter (Randall), who lives with his teenage niece April (Lili Hunter) and is engaged to marry his secretary Jenny Wells (Betsy Drake). Rockwell, like George, once worked for a movie fan magazine, and his own sole published article was entitled, “Will Success Spoil Bobo Brannigansky?” (It’s a surname that seems to come straight out of Preston Sturges, whose 1944 The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek Tashlin would loosely adapt a year later, in Rock-a-Bye Baby.) And the only remnants of the Faust theme is that Rockwell does acquire fame, fortune, and the affection (if not the love) of Rita Marlowe, the girlfriend of Bobo Brannigansky (played by Mickey Hargitay, the real-life husband of Jayne Mansfield), but then unexpectedly gives up all three for the pleasures of rural chicken farming. And the fame and fortune come to him as an adman, not as a Hollywood screenwriter — someone who acquires the endorsement of Rita Marlowe for Stay-Put Lipstick in exchange for making Bobo Brannigansky jealous, and at the cost of almost permanently alienating his girlfriend Jenny. Thanks to this endorsement, he becomes first vice-president and then finally president of the La Salle Jr., Raskin, Pooley & Crocket Advertising Agency — replacing Irving La Salle, Jr. (John Williams), who has meanwhile fulfilled his own longtime dream by leaving the firm to become a horticulturist who grows and develops roses. (When Rock pays his former boss a visit in the latter’s greenhouse, Junior applauds the hero’s ascension to the top with a chilling line that becomes virtually the film’s motto: “Success will fit you like a shroud.” And sure enough, it proves to be a hollow victory because Rockwell can’t keep his pipe lit. As a psychiatrist reportedly told him some time ago, half of him wants to succeed and half of him wants to fail, with the result that he doesn’t know whether to inhale or to exhale. Similarly, “got it made” is a phrase that this movie keeps repeating so many times, in so many different ways, like a desperate mantra, that it begins to sound increasingly sinister.

The movie’s climax, aptly filmed in expansive CinemaScope, spells all this out in glitzy neon. After Hunter, who has just been appointed president of his company, says goodnight to the office cleaning ladies, the scene segues into a solipsistic musical number played out to an unseen celestial chorus chanting “You’ve got it made” as he literally sees his name in lights, dancing deliriously through the empty executive board room under various shifting forms of expressionistic lighting. Drawing on his background as a former animator, Tashlin makes it all look like a crazed cartoon, with delirious fadeouts to yellow, red, green, and blue, a vision of Rita Marlowe clothed exclusively in gold coins and dollar bills, and surrounded by singing or signifying typewriters and switchboards celebrating his ascension to power and status. In a way, it’s a reprise to Rockwell’s earlier victory-plateau, when his colleague Henry Rufus (Henry Jones) presents him with the key to the “executive powder room,” cuing in a previous chorus by the same celestial choir. (As Bogdanovich wrote in 1962, “The scene in which Tony Randall is moved to joyous tears when given the key to the executive washroom is exaggerated so little that it becomes almost terrifying in its basic truth. This was a large part of Tashlin’s particular genius: he was honest, exaggerating only slightly to make a point.” (This was another facet, one might add, that distinguished him from Axelrod.)

But by the sequence’s end, Hunter also discovers that he can’t keep his pipe lit. In the movie’s Freudian shorthand, this means that he doesn’t really feel successful after all , at least until he discovers that, as he explains it to Jenny, it is his average-guy mediocrity that makes him a success, not his anxiety-ridden elevator to power and status.

The fact that Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? was Tashlin’s most avant-garde and political film undoubtedly also made it one of his most misunderstood — rivaled, perhaps, only by Chaplin’s A King in New York, also released in 1957 (albeit only in Europe), and paralleling Tashlin’s vision of America in many important aspects (although it goes further in highlighting many of the hysterical 50s excesses, such as the McCarthyite witchhunts, that were systematically left out of Hollywood pictures). Both directors, anticipating Jean-Luc Godard’s journalistic directive that one can — and must — place “everything” in a film, create dystopian versions of New York in which TV and advertising (rightly perceived as synonymous) completely obliterate the divisions between public and private. Both jeremiads correctly and prophetically perceive that advertising not only competes with contemporary American culture; it is contemporary American culture. A corollary perception, which both pictures spell out in numerous ways, is that television, far from facilitating communication and social interaction, effectively replaces them. Significantly, when Rock Hunter wants to know what has happened to his niece or even, at the onset of his celebrity, what Rita Marlowe is saying downstairs and immediately outside his apartment, on the street, he logically turns on his TV set. And as his Madison Avenue colleague points out, he doesn’t have to worry about locating the right channel, because the media’s Marlowe coverage extends to all the channels (an eerie prophecy of such relatively recent news events as the deaths of Ronald Reagan, Frank Sinatra, and Michael Jackson).

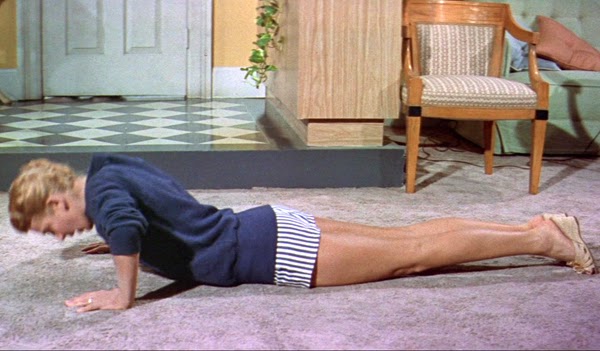

It’s worth considering that one of the main charges hurled against both A King in New York and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? was vulgarity, predicated on the assumption that it was Chaplin’s treatment of (say) plastic surgery and Tashlin’s treatment of male Americans’ fixation on large female breasts that were tasteless, presumably not cosmetic surgery and breast fixation themselves. Andrew Sarris expressed this position against Tashlin as follows: “One can approve vulgarity in theory as a comment on vulgarity, but in practice all vulgarity is inseparable. To ridicule Jayne Mansfield’s enormous bust in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? may be construed as satire, but to ridicule Betsy Drake’s small bust in the same film is simply unabashed vulgarity.” To which one could reply that neither bust is ridiculed; it’s the breast worship engulfing and oppressing both women that Tashlin is mocking — more obviously in the case of Betsy Drake’s character when she winds up passing out from her breast-expanding exercises, before taking a doctor’s advice and purchasing falsies. But by broaching this subject at all, Tashlin’s most daring forms of irreverence could also be mistaken for exploitation. As Diane Johnson, the screenwriter of The Shining, once noted. “In the 1950s there were fewer words for oppression.”

To complicate matters, discussions of class tend to remain sufficiently taboo within American culture to make charges of vulgarity a partial displacement and relocation of certain class biases that are unacknowledged as such. (In a similar fashion, many of the ill-conceived descriptions of writer-director Samuel Fuller as a “primitive” might be considered a displacement of the reluctance to confront his working-class origins.) If English critic Raymond Durgnat in 1969 could spot the same “mixture of despair and acquiescence” in both Tashlin and Andy Warhol, most of his Anglo-American contemporaries were too busy segregating the two into the mutually exclusive categories of entertainment and art to ponder the salient parallels. Thus the “coldness”, distanciation, and ironic playfulness that critics cited in defense of Warhol’s sophistication as a dandy and artist were all regarded as negative factors in relation to Tashlin — proof even of his alleged corruption as an entertainer. While Warhol was declared an acute social analyst who perfectly understood the art market (i.e. the class to which he catered), Tashlin was branded as a man with a breast fixation who was too implicated in what he was satirizing to qualify as a serious artist. Different strokes for different folks — and of course most of the people whom Tashlin addressed didn’t read auteurist criticism.

Tashlin once defined his turf as “the nonsense of what we call civilization,” which he thought deserved both exuberant celebration and ridicule — a combination that was not dissimilar to Warhol’s own ironic ambivalence, expressed in a radically different social milieu.

A few of the jokey period references in Rock Hunter may require glosses. I count ten allusions to other mid-50s Fox releases or stars then under contract to Fox, the most significant of these being Marilyn Monroe. She’s never mentioned, but Mansfield is obviously being used as a broad parody of her, as she was in The Girl Can’t Help It, and there’s even a veiled allusion to The Brothers Karamazov (a treasured Monroe project) and a bit about Rock and Rita getting hitched in Connecticut (where Monroe married Arthur Miller).

Were these references product placement? Tashlin’s admission of complicity with the culture he was lampooning? Probably some of both, which also applies to the celebrations and ridicule of rock music in The Girl Can’t Help It. Rock Hunter seems revolted by American notions of success, but when all of the major characters finally renounce these ideas to follow their unglamorous dreams, including even the mating of Rock and Rita’s two major sidekicks, the movie seems to mock them. We can’t quite believe that Randall’s ad executive becomes a chicken farmer, and neither can Tashlin or Randall. Maybe that’s why the characters turn up in front of a stage curtain at the end, becoming abstract Brechtian commentators on their own dilemmas.

Still, when Tashlin acknowledges being implicated in what he’s satirizing, he’s good-natured and relaxed about it — making his populism and optimism seem genuine rather than forced. He has a charming way of being devastatingly critical, affectionate, and hopeful at the same time.