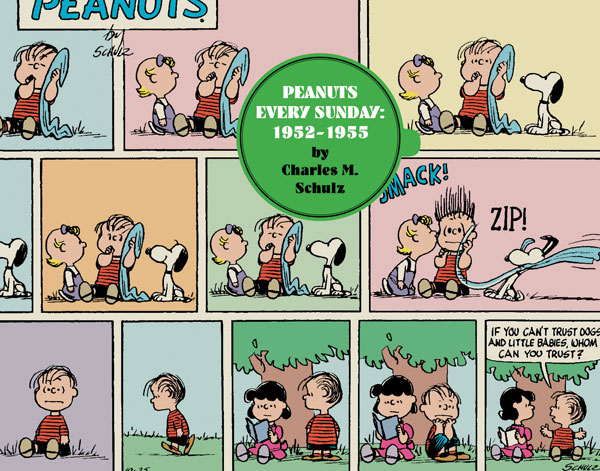

Gary Groth of Fantagraphics Books commissioned me to write this Introduction to the first volume of Charles Schulz’s Sunday color strips of Peanuts, covering the early 1950s, which was published in November 2013. — J.R.

“…I’ve made a lot of mistakes down through the years doing things I

never should have done. But fortunately, in a comic strip, yesterday

doesn’t mean anything. The only thing that matters is today and tomorrow.”

— Charles Schultz to Gary Groth (“At 3 O’clock in the Morning,”

Comics Journal #200, December 1997)

It was one thing to read Sunday color Peanuts comic strips from 1952 to 1955 at the rate of one per week, when they came out — and not only because they would have wound up in the trash like the rest of the Sunday paper, long before my brothers and I went to sleep that night. And it’s quite another thing to read them all today, piled together in the present volume, one after the other, seven or eight panels at a time, as if they’re the successive chapters of an ongoing serial — or maybe just the latest portions of an endless white picket fence that stretches towards some version of infinity or eternity (or at least roughly half a century of dependable continuity, in any case).

It’s likely that I saw a good many of these strips between the ages of eight and thirteen. If the Birmingham paper my family had delivered each morning had carried the preceding weekday black and white Peanuts strips that started fifteen months earlier, shortly after I entered the first grade, my curiosity as an early reader might have brought me to a few of them, even though I’m fairly sure I wouldn’t have understood any of the jokes — if jokes, indeed, are what those enigmatic exchanges and incidents consisted of. I’m confident, in any case, that whenever I first encountered Peanuts, the full extent of my curiosity never went beyond the issue of what these kids with beach-ball heads were saying, thinking, and/or doing that particular week. And, at least in the world of Peanuts as I understood it even then, saying and thinking was at least as important as doing, and maybe even indistinguishable from the latter.

The near-equivalence between thinking, saying, and doing is surely an important part of what made Peanuts different from the strips surrounding it. But it might be equally instructive to inquire what some of the common traits were between Peanuts and some of its Sunday morning siblings. The notion of a world ruled largely by an authoritative, sometimes bossy female was arguably a common trait in Blondie, Bringing Up Father (more popularly known as Jiggs and Maggie), The Katzenjammer Kids, Li’l Abner (as ruled by Mammy Yokum), and Mary Worth — in contrast, say, to Barney Google and Snuffy Smith, Dick Tracy, Gasoline Alley, Little Orphan Annie, and Mutt and Jeff. It’s worth adding, however, that the dominance of Lucy over Charlie Brown wasn’t as apparent at the beginning, while she was still just a tyke, as it would become later—even though an older girl, a redhead named Patty, would already anticipate some of her traits (in contrast to the usually more sweet-tempered Violet), and Lucy herself would grow up so quickly that she would soon put her youthful subservience behind her.

In 1975, her creator, Charles Schultz, pointed out, “As the strip progressed from the fall of the year 1950, the characters began to change. Charlie Brown was a flippant little guy, who soon turned into the loser he is known as today. This was the first of the formulas to develop. Formulas are truly the backbone of the comic strip. In fact, they are probably the backbone of any continuing entertainment.”He added that, among the other characters, Lucy had already developed at least part of her fussbudget personality during the first year of the strip, inspired by some of the traits of his oldest daughter, Meredith. Furthermore, “Snoopy was the slowest to develop, and it was his eventually walking around on two feet that turned him into a lead character. It has certainly been difficult to keep him from taking over the feature.”

In the early appearances of Snoopy, it often isn’t clear if Schultz is postulating a dog who thinks he’s human, a human who thinks he’s a dog, or some perpetual, seesawing arrangement between these two peculiar mismatches. Eventually, one might postulate that he evolves into some version of all three; Schultz acknowledged in 1975 that his “appearance and personality have changed probably more than those of any of the other characters.” But for the Italian semiologist Umberto Eco, he is simply a dog who can’t accept being a dog — an animal who “carries to the last metaphysical frontier the neurotic failure to adjust.”

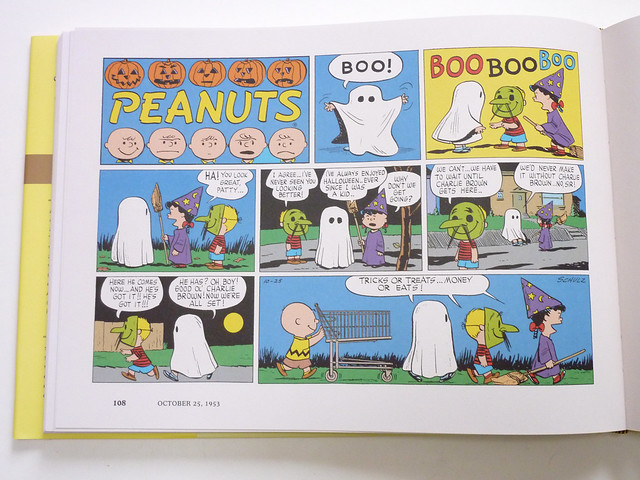

On Halloween, 1952, we see him sporting a fright mask to accompany two boys under bed sheets, and proving to be just as ineffectual as they are when it comes to scaring Lucy. The previous week, we saw him dancing some sort of hornpipe to the classical strains of Schroeder’s toy piano, then brooding and sulking afterwards about Charlie, Schroeder, and Patty leaving him alone rather than inviting him over to spend the night — and then defiantly entering his humble doghouse to watch TV in order to “prove” he doesn’t need their company anyway. Or does he?

In mid-February 1953, he thinks her outsmarts Lucy when he devours two of her cookies while she goes away to answer the doorbell, then winds up baffled when she figures it out afterwards, despite her eccentric and seemingly chaotic method of counting. And five weeks later, Schultz combines two of Snoopy’s specialties, dance and consuming human food — dancing his hornpipe to Schroeder’s rendition of Modest Moussorgsky’s “Hopak,” then becoming miffed when he gets banished to the kitchen at lunchtime, only to discover, after Lucy brings him ‘three kinds of sandwiches” and “a salad, cake, ice cream and hot chocolate” — so much human food, in fact, that two separate dialogue bubbles are required to accommodate Lucy’s list. This leads him to conclude (but to himself only), “Pride is a foolish thing!”

Consider the multiple forms of fantasy conceit that Schultz manages to shoehorn into the latter strip: Schroeder performing “Hopak” (and on a toy piano, no less); Snoopy performing his dance (again, at the request of Charlie Brown); five kids including Linus clapping their encouragement without any signs of amazement about either feat (four of them barking out, “Hey!” for rhythmic emphasis); Lucy explaining to Snoopy why he has to go to the kitchen and then, as he sulkily starts to head for home instead, delivering a veritable banquet to him (neither act impossible, but both highly unlikely in most of the worlds we’re familiar with); Snoopy undergoing querulous resentment about not being treated like a human before being startled and then placated by a bounty of human food, which leads to some philosophical self-deprecation. And Snoopy’s taste for human food—not only cookies, sandwiches, salad, cake, ice cream, and hot chocolate, but also candy three weeks later, and bread the following week—clearly functions as an obsessive theme, perhaps in part because, like TV and choreography, it implies a kind of membership in the human race, although his desire to become a member gets expressed only privately, to himself. (Presumably and peculiarly, his talent for both dancing and playing Trick or Treat are viewed by the kids as more proper canine attributes; and if Snoopy ever expresses his feelings of maladjustment to other animals, we don’t hear about it.)

In short, more than a few impossibilities coupled with several highly unlikely human and nonhuman responses are in full operation here, yet we can accept all of them as naturally and as effortlessly as if we were watching a string of quite ordinary events.In a similar fashion, we don’t really care about the fact that Snoopy’s doghouse carries a TV antenna while the unseen TV set inside apparently functions without an electric cord, even though the pool of luminosity spilling out of the doghouse interior is every bit as bright as the crescent moon in the sky.And we’re not even encouraged to ask whether Snoopy’s Halloween mask was suggested and/or provided by Charlie Brown or whether he managed to acquire it and/or put it on following his own initiative.

Later, in September 1953, we see him self-consciously and mischievously smile, grin, turn his head, flip upside down, and frown in front of Charlie Brown’s camera, then laugh at his photographer’s exasperation. But then, a week later, we see him failing in his effort to imitate Lucy in gracefully going down a playground slide.And a week after that, we see him trying to behave like an ordinary dog by growling at a bird, then chasing after it and barking until he’s eventually gasping with exhaustion—at which point the bird yawns and Snoopy sighs at all this wasted effort. Yet apart from his recurring hornpipes and a few other passing fancies — such as his skipping rope with Lucy in separate strips in May and July 1955 — we don’t yet see Snoopy walking around on two feet very often in this early phase of Peanuts, and when he does (as in one of the black and white dailies in November 1955, when he’s trotting that way behind Lucy), Charlie Brown warns him that he’s asking for trouble. Once he fully enters a world of his own, however, his trouble will become more metaphysical or philosophical than social — as it sometimes does for Charlie Brown, in spite of his own everyday humiliations.

How does Schultz do it? The testimony of one fantasy-driven filmmaker about another — independent writer-director Sara Driver speaking to me in an interview a few years ago — suggests one important clue: “You know, I’m such a lover of Jacques Tourneur’s films, and I remember reading about him and how if you anchor things in a sense of reality, you can go anywhere from there.”This becomes especially true when a sense of reality is grounded in a solid grasp of character, so that the reality of, say, a frigid, newlywed Serbian fashion artist (Simone Simon) in Cat People (1942) and quite a few non-zombies in I Walked with a Zombie(1943), Tourneur’s first two pictures for Val Lewton — like that of Driver’s schizophrenic heroine in You Are Not I (1981) and a schleppy and lazy jazz musician in When Pigs Fly (1993) — enables us to accept many kinds of outlandishness in those films (such as a heroine who switches bodies with her sane sister, or a dog belonging to the jazz musician who has jazz dreams of his own, featuring other musical dogs). And the reality of Charlie Brown, Lucy, Schroeder, Linus, Patty, and yes, even Snoopy — and, most of all, the shifting and volatile emotions of these characters, human or canine — allows Schultz to get us to accept any number of absurdities, anomalies, inconsistencies, and strategic absences (starting with the nonappearance of adults) involving what they say, think, and do, even (and maybe even especially) when all three of these activities get collapsed into one.

***

A lifelong movie fan, Schultz occasionally referred to the “camera angles” in his strips, despite the absence of any camera, to describe his habitually adopted eye-level angle of vision. His main filmic reference points were obviously American — William Wellman’s Beau Geste (1939), Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941), Norman Foster’s Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier (after the 1955 release of this this live-action Walt Disney adventure set off a national craze in coonskin hats, occasioning one of Schultz’s infrequent excursions into the topical), along with Laurel and Hardy and many Saturday matinee serials. But if any cinematic cross-references are helpful in getting at Schultz’s style and vision, one could argue that, in at least a few respects, the late films of Yasujiro Ozu come closer to the mark — without forgetting that Ozu himself was such a fanatical devotee of Hollywood (as evidenced even by the movie posters glimpsed on the domestic walls of his characters) that his sharpest critic, Shigehiko Hasumi, has pointed out that even the weather in Ozu’s movies is closer to that of Southern California than to the more drizzly weather of Japan. Obviously, Ozu’s characters encompassed more than small fry, but the minimalistic canvas of their everyday domestic events and rituals, the repeated use over decades of the same actors (as a rough equivalent to Schultz’s reliance on the same characters) and the same low and eye-level “camera angles”, and the quiet and deadly slow burns and petty frustrations of family and neighborhood entanglements all suggest some of the same habits and preoccupations.

A lifelong movie fan, Schultz occasionally referred to the “camera angles” in his strips, despite the absence of any camera, to describe his habitually adopted eye-level angle of vision. His main filmic reference points were obviously American — William Wellman’s Beau Geste (1939), Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941), Norman Foster’s Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier (after the 1955 release of this this live-action Walt Disney adventure set off a national craze in coonskin hats, occasioning one of Schultz’s infrequent excursions into the topical), along with Laurel and Hardy and many Saturday matinee serials. But if any cinematic cross-references are helpful in getting at Schultz’s style and vision, one could argue that, in at least a few respects, the late films of Yasujiro Ozu come closer to the mark — without forgetting that Ozu himself was such a fanatical devotee of Hollywood (as evidenced even by the movie posters glimpsed on the domestic walls of his characters) that his sharpest critic, Shigehiko Hasumi, has pointed out that even the weather in Ozu’s movies is closer to that of Southern California than to the more drizzly weather of Japan. Obviously, Ozu’s characters encompassed more than small fry, but the minimalistic canvas of their everyday domestic events and rituals, the repeated use over decades of the same actors (as a rough equivalent to Schultz’s reliance on the same characters) and the same low and eye-level “camera angles”, and the quiet and deadly slow burns and petty frustrations of family and neighborhood entanglements all suggest some of the same habits and preoccupations.

Where Ozu and Schultz decisively part company is in how they cope with fantasy -– not at all in the case of Ozu, who adheres strictly to the familiar and the feasible, and so frequently and integrally in the case of Schultz that it sometimes becomes hard to separate the fantasy conceits from the everyday emblems and rituals. The minimalistic canvas tends to equalize all the elements in Schultz’s universe, including all the elemental traits, so that inexpressiveness and expressiveness are less than an inch apart, and fullness and emptiness can sometimes be no less difficult to separate. Even while objecting to some of the cuteness and debilitating “good taste” of Peanuts in a 1959 essay, critic Donald Phelps conceded that “Charles Schultz may be the most accomplished master of blankness in contemporary art since Mark Rothko drifted onto the scene with his filets of Grand Canyon. He can fluff out an almost gagless strip with dogs and children doing tumble-weed dances. (This has produced some of his funniest panels: those featuring his best character, Charlie Brown’s dog, Snoopy.) He posts his characters against great swatches and bandaids of empty space and a little stubby grass, so that the vapid doodling of figures takes on the deadpan suggestiveness which perked up Buster Keaton’s fascination for so many years.” As Eco reminds us, Charlie Brown is an epic hero who is invariably referred to by his whole name, even by his unseen mother, so the coexistence of small events against those great swatches and bandaids is part of what makes his world seem so real to us—that is, tiny from a cosmic vantage point yet vast from the close quarters of our childish perspective. It’s this sense of relativity that remained with Schultz at the same time that his characters and their predilections were still being shaped, and this amused and evenly balanced distance remains fundamental to his wit.