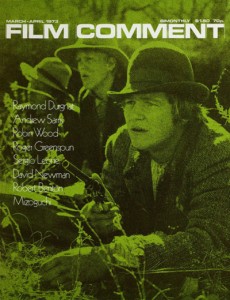

From Film Comment. In a few slight particulars, I’ve taken the liberty of editing my 30-year-old self 47 years later. I’ve also omitted the remarks about several recent French film books (apart from Benayoun’s) that concluded this column. — J.R.

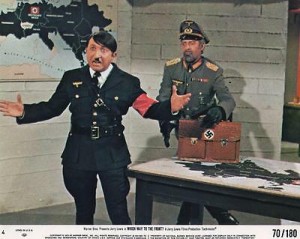

The admiration of French cinéastes for Jerry Lewis continues to be in evidence everywhere. In an interview in the current Time Out [in London], Jean-Pierre Gorin pays his own respect to Lewis’s greatness – over the protests of his interviewers – for the “experimental” and “scientific” ways that he deals with sound and image, cutting and plot construction, adding that Godard has seen WHICH WAY TO THE FRONT? (which “is almost mathematical if you look into it deeply”) five times. And in DOCTEUR POPAUL, Chabrol’s latest film, Mia Farrow is furnished with eyeglasses and buck teeth to make her resemble Julius Kelp in THE NUTTY PROFESSOR, while Jean-Paul Belmondo is run through a series of sight-gags that are clearly Lewis-inspired.

To my mind, Chabrol’s pastiches are vastly inferior to Lewis’s originals, and DOCTEUR POPAUL is less worthy of American release than Chabrol’s earlier OPHÉLIA, LA RUPTURE, or JUSTE AVANT LA NUIT (the last-named, a perverse and elegant companion-piece of LA FEMME INFIDÈLE, is probably the best of the lot). However, if or when DOCTEUR POPAUL should open in the states, one can easily predict that it will receive more critical attention and respect than any of the last few films directed by Lewis. In 1957, Godard wrote a review praising Lewis’s mentor Frank Tashlin, and optimistically predicted that “In fifteen years, people will realize that THE GIRL CAN’T HELP IT served then – that is, today – as a fountain of youth from which the cinema now – that is, in the future – has drawn fresh inspiration.” But ironically, fifteen years later – that is, last summer – Tashlin died in California an almost totally forgotten figure who was never really recognized in the first place by the general public, while Godard is known the world over as a narrative innovator.

I don’t mean to suggest that Tashlin’s innovations in open form were superior to Godard’s, even if they came first. Obviously a central part of Godard’s achievement in the Sixties was to bring to self-consciousness a multitude of styles and techniques that existed all around him in the Fifties. But it seems to me somehow disproportionate to praise the use of, say, color filters and advertising slogans in the cocktail party sequence in PIERROT LE FOU, without realizing that they derive from stylistic departures that are even wilder – and, incidentally, more successfully as satire – in WILL SUCCESS SPOIL ROCK HUNTER?

In certain contexts, Tashlin’s and Lewis’s deformations of landscape, architecture, face, body, voice, and syntax may be seen as startling surreal glimpses into the nature of contemporary America. Perhaps what makes this vision so unpalatable to many Americans – including myself at times – is its implicit representation of American thought as an exclusively infantile activity, a tendency that makes Lewis’s public and TV appearances even more disturbing and/or revolting, because they are less subject to aesthetic justifications, But the Tashlin-Lewis vision of America, which simultaneously mocks and celebrates an infant sensibility, also has a baby’s energy, freedom, and abandon in going after whatever it wants or needs. The cavalier attitude often conveyed in a Tashlin film was that the director might interject whatever he wanted, at any given moment, for whatever reason: a rock number, a fantasy interlude, an editorial aside, a change in the size of the screen, an abrupt shift in the soundtrack. Such a capacity to bounce about a narrative at will was undoubtedly the principal reason that Godard learned from Tashlin, and one could say that, mutatis mutanidis, Lewis has benefited from the same instruction.

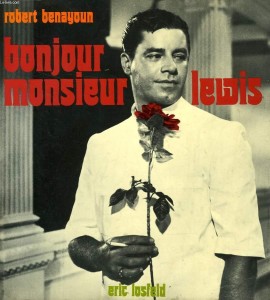

Robert Benayoun’s Bonjour Monsieur Lewis, published a few months ago by Eric Losfeld, brings together virtually everything you wanted to know about the French passion for Jerry Lewis, but were afraid to ask; or, if you should share this passion, just about everything you could conceivably want to know about Jerry Lewis. (For example, the bibliography includes Instruction Book for Being a Person, a privately printed collection of “moral and edifying maxims…that Lewis offers to his intimate visitors”). It is unlikely that Lewis will ever find a more faithful and entertaining explicator than Benayoun, who has championed, befriended, chronicled, and celebrated Lewis with more sustained energy than any other French critic, and writes with considerably more bite and wit than Lewis himself (to judge from the latter’s recent book about filmmaking).

In an interesting analysis of the Lewis Question in The American Cinema, Andrew Sarris took a covert swipe at Benayoun when he remarked, parenthetically, “We will not speak here of a Positif critic who so resembles Jerry Lewis that hero-worship verges on narcissism.” To counter this charge, Benayoun opens his book with a photograph of himself standing in front of a larger picture of Lewis, and prints beneath this the dedication, “To Andrew Sarris, the Spiro Agnew of American criticism.”

Whether or not Benayoun resembles Lewis can be argued elsewhere; what is clear from Bonjour Monsieur Lewis is how saturated Benayoun is in the personality and obsessions of his subject. Over 368 large-format, lavishly-illustrated pages — a layout suggesting the breadth and ambition of Truffaut’s Hitchcock book in many respects — Benayoun traces the dimensions of Lewis’s career and accomplishments with unflagging absorption, beginning with his first article on Lewis in 1957 (“Simple Simon, or the Anti-James-Dean”), and continuing up through a consideration of a Lewis-directed episode about muscular dystrophy for a TV series in 1971. After this come no less than seven appendices, the last of which is a detailed filmography.