From Sight and Sound (March 1992). –- J.R.

There was a discernible change of emphasis this year’s Rotterdam

Festival under its new director, Emile Fallaux. Certainly, there were

fewer intellectual and scholarly interests than in the reign of Marco

Müller, who has moved on to Locarno,although the creation of a new

organization called ‘The Limits of Liberty’ to promote free expression

for filmmakers (somewhat after the model of PEN) signaled a new

activist impulse. With selections now made by a team of Dutch

programmers rather than a single individual, Rotterdam has arguably

become more of a Dutch event than it was under the extended rule of

the late Hubert Bals, who tended to shun native product. But one welcome

constant is a passionate defense of the marginal and surreptitious, and

an overall sense of equality that puts studio tyros and independents on

the same footing.

One of the most striking films this year was Zhang Yuan’s Mama, an

independently Made, banned work from mainland China about

mentally handicapped children. Alternating between an emotionally

subdued fictional story in black and white about a mother and her

retarded son and highly emotional documentary interviews in color

video with the real-life counterparts, the film sets up a neo-Brechtian

strategy with complex dividends. (Interestingly, the screenwriter,

Qing Yan, appears as both the fictional mother and as herself in a

video interview.)

At the other end of the economic scale was Leos Carax’s

ravishing Les Amants du Pont-Neuf, resurrecting the Alex

(Denis Lavant) of Carax’s earlier Boy Meets Girl (1983)

and Mauvais sang (1986) as a Parisian street punk who

falls in love with a slumming street artist (Juliette Binoche).

The true star of the film, however, is the gargantuan studio

set of Pont-Neuf and environs, brought to life by a dreamlike

conceit -– Parisas plaything — that has serviced French

cinema from René Clair to Jacques Tati. Decorating his

plaything with everything from fireworks to snow, Carax

mounts a moving love story that fully earns its homage to

L’Atalante in the closing sequence.

A more aberrant — therefore more characteristic — Rotterdam specialty

was Qiu Gangjian’s A Ying (Ming Ghost), a Taiwanese remake of

Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1951) conceived less as a meaningful

statement about relative truths than as a pretext for diverse

formal hijinks and decadent campy notations. Directed by the man

who translated Genet into Mandarin, the movie revels in outsized

gestures played against stark decors and a mannerist mise en scene

that alternately elevates and undermines those gestures. Unabash

midnight movie devoted to laying waste the traditional — almost as

if a John Waters or a David Lynch were set loose inside a Chinese opera.

A much more sober outsider’s look at Chinese culture is

Shoot for the Contents by Trinh T. Minh-ha, a US-based,

Sorbonne-educated writer and filmmaker who embarked

on this project as an indirect way of investigating her own

Vietnamese roots. (Her next documentary will be about

India, the other major source of Vietnamese culture.)

Disconcerting for those expecting documentaries about

China to be packaged as purveyors of authoritative facts,

the film is more concerned with finding ways of thinking

about China — not trying to speak about what it doesn’t

know, though enlisting certain Chinese arts (most notably

architecture and calligraphy) in its strategies of poetic

evocation. Much of the dispersed presentation of Shoot

for the Contents — whose title alludes to a Chinese

guessing game — consists of speculative conversations

and diverse kinds of visual displacement, all of which

contrive to approach China ‘cubistically’, through a

series of mutually contrasted outsider positions and

layered perspectives.

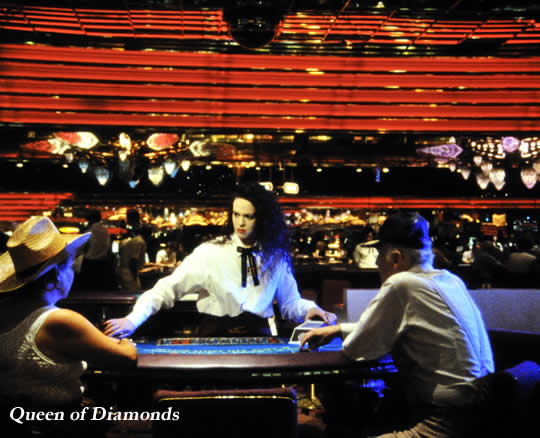

Rotterdam regular Luc Moullet was back with La Cabale des oursins, a hilarious short in defense of slagheaps – scornfully omitted from official maps, but lovingly surveyed by Moullet, both physically and philosophically. In Nina Menkes’ Queen of Diamonds, a powerful minimalist non-drama set in Las Vegas, the marginal — in this case an abandoned. wife (played by Tinka Menkes) — becomes downright luminous, through landscapes and events in which the heroine figures as a peripheral detail in a mysterious expanse.

Taking place just before Berlin, Rotterdam invariably loses some selections to the bigger festival — a regrettable concession to the vanity of programmers rather than a service to spectators at either event. But as always, the festival made up for these losses by the intimacy and intensity of its atmosphere.