Written for the December 2022 issue of Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. — J.R.

I’ve recently been working on a book that collects my uncollected film, literary, and jazz criticism, ordering all my inclusions chronologically so that they’re allowed to commingle, meanwhile exploring ways that all three of these art forms (film, literature, music) can inform and reflect one another. Because this project rejects the “targeting” mentality ruling academic presses and their all-powerful publicists—which follows the Reaganite economic principle of exploiting and exhausting markets that already exist, not proposing new ones—it took me some time to find a publisher.

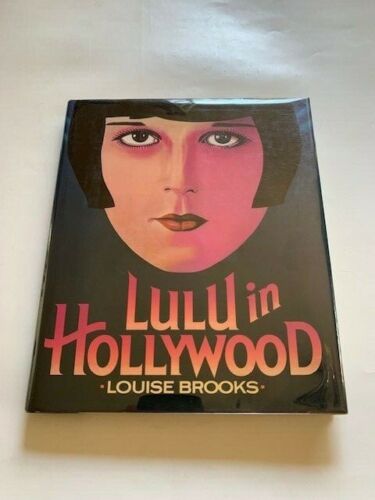

Still more recently, I’ve been rereading Louise Brooks’ informative, thoughtful, and beautifully written Lulu in Hollywood, a collection of essays combining autobiography with criticism, film history with social and fashion history, and even a certain kind of fiction with non-fiction.

The latter combination requires some explanation. While recounting her memories of her own acting in films (especially Beggars of Life and Pandora’s Box) and of Humphrey Bogart, Charlie Chaplin, W.C. Fields, Greta Garbo, Lillian Gish, the neglected director Edmund Goulding, and the even lesser known Pepi Lederer (lesbian niece of Marion Davies, older sister of screenwriter Charles Lederer, and close friend of Brooks who committed suicide at the age of 25), Brooks renders scenes in such fulsome and intricate detail—extended dialogue, facial expressions and gestures, locations, furnishings, clothes, food and drink at meals—that it quickly becomes apparent that she must be fleshing out whatever she can remember with imagined specifics. So it’s impossible at times to separate her facts from fictional elaborations. And because, by her own account, Brooks was a trained dancer who became an untrained film actress who could only play herself (an “unrepentant hedonist,” as Kenneth Tynan once described her, whose defiant independence and intransigence eventually sabotaged her Hollywood career), before becoming, years later, a very skillful writer while remaining an untrained bookish intellectual, she shares a trait of many major filmmakers by regarding non-fiction and fiction as two sides of the same coin, or, to mix metaphors, siblings searching for the same truths.

“Writing is perhaps the most disciplined of all the arts,” she writes in the second paragraph of her essay on Pepi Lederer, which suggests that for her, it was another kind of dance that required even more concentrated energy and work. And because the dancing prose of Lulu in Hollywood could be described as a rethinking of her past that requires the diverse disciplines of research, analysis, historical reflection, autocritique, and putting words together—in short, all the activities of a critic—Brooks offers me a helpful model in how to proceed with my own work.