From the Chicago Reader (December 14, 1990). Note: Twilight Time has recently released The Russia House on Blu-Ray. — J.R.

THE RUSSIA HOUSE

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Fred Schepisi

Written by Tom Stoppard

With Sean Connery, Michelle Pfeiffer, Roy Scheider, James Fox, John Mahoney, J.T. Walsh, Ken Russell, David Threlfall, and Klaus Maria Brandauer.

HAVANA

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Sydney Pollack

Written by Judith Rascoe and David Rayfiel

With Robert Redford, Lena Olin, Alan Arkin, Tomas Milian, Raul Julia, Richard Farnsworth, Mark Rydell, Daniel Davis, and Tony Plana.

The Russia House and Havana are both lavishly mounted love stories, packed with action and developed in relation to political intrigues abroad. What’s surprising about both is that although they’re Hollywood movies to the core, the American characters aren’t exactly the good guys.

In The Russia House the only important American characters are villains, while the hero is British and the heroine Russian. In Havana the hero is as American as they come, and he certainly behaves heroically, yet the film as a whole raises doubts about whether he has missed the boat, historically speaking. We entertain fewer doubts in this respect about the heroine, a Swede with an American passport who’s married to a Cuban. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 24, 2000). — J.R.

Waking the Dead

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Keith Gordon

Written by Robert Dillon

With Billy Crudup, Jennifer Connelly, Molly Parker, Janet McTeer, Paul Hipp, Sandra Oh, and Hal Holbrook.

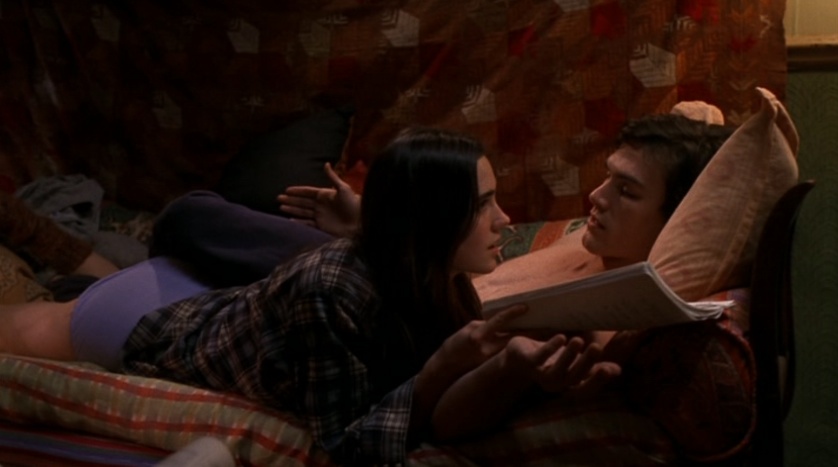

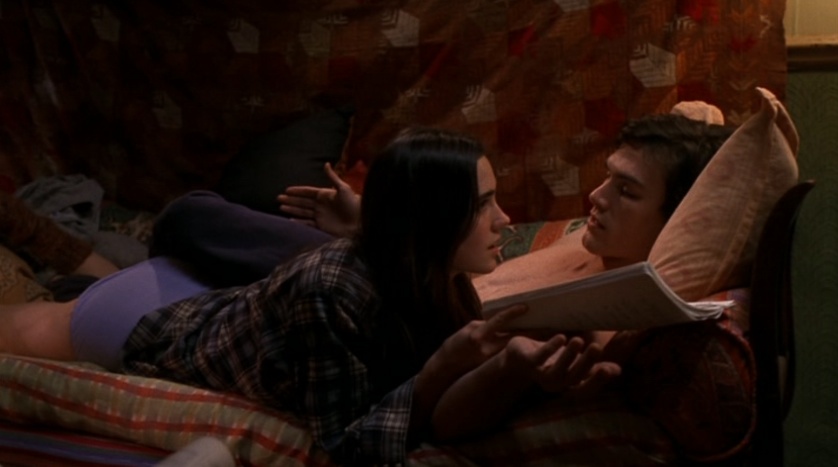

I can’t make any great claims for Keith Gordon’s fourth feature as a director — a tragic love story that might be described as a political allegory, limited by the affective range of its lead actor (Billy Crudup), who plays a smarmy politician, and by the smudgy articulation of some secondary details. Yet the movie has a quality and intensity of feeling that provoke respect and a sense of fellowship — something that makes me cherish some of its attributes.

I can cite only one unequivocal reason for seeing Waking the Dead, and that’s Jennifer Connelly, who plays Sarah Williams — a Catholic activist who, when the story opens, seemingly dies when the car she and two pro-Allende Chileans are driving through Minneapolis is bombed. What makes Connelly so remarkable isn’t her character’s radicalism but her capacity to keep the character fresh every time she appears and to leave a lingering impression that makes the hero’s (and the movie’s) sense of loss acute. Read more

From the March 1980 issue of American Film. – J.R.

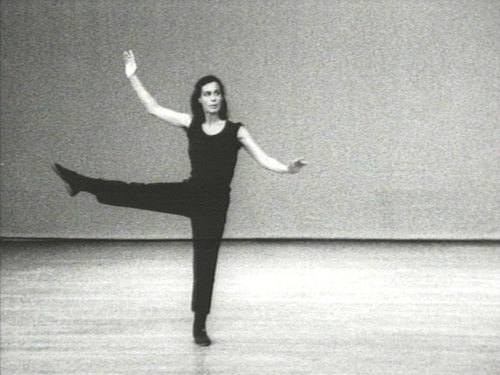

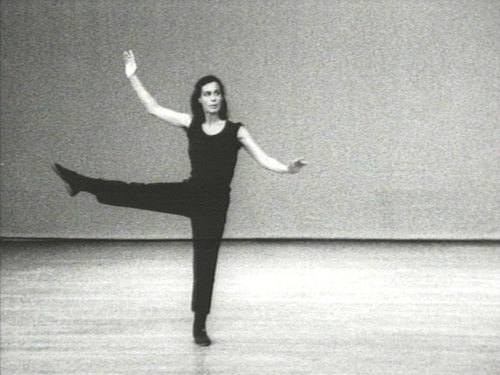

It’s pretty apparent to anyone who meets avant-garde filmmaker Yvonne Rainer for the first time that she used to be a dancer. But one probably has to see at least one of her four challenging features in order to perceive that she used to be a choreographer, too. And it’s only after one considers her in both these capacities that one starts to get an inking of what her viewpoint and her art are all about.

The first time I met her — three and a half years ago, at the Edinburgh Film Festival — Rainer reminded me in several ways of writer and filmmaker Susan Sontag. It wasn’t merely the somewhat glamorous positions that both women occupy on respective intellectual turfs. There was also a kind of spiritual resemblance that seemed to run much deeper: voice tone, appearance, wit, grace, and coolness masking an old-country sense of tragedy and suffering.

***

In Edinburgh Rainer delivered a lecture called “A Likely Story,” about the use of narrative in films. In the course of her remarks, she made it clear that her own “involvement with narrative forms” hadn’t always been “either happy or wholehearted,” but was “rather more often a dalliance than a commitment.” Read more

A short review commissioned by Film Comment (July-August 2002), which left out the asterisk in the title. — J.R.

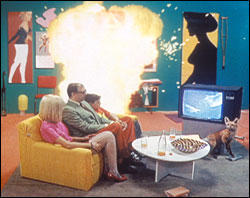

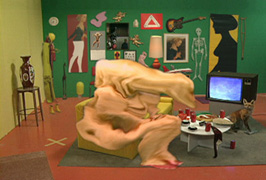

*Corpus Callosum

I recently read in a film festival report that Michael Snow’s new 92-minute feature was a bit longer than it needed to be. This conjured up visions of a test-marketing preview — cards handed out at Anthology Film Archives with questions like, “Would an ideal length for this be 82 minutes? An hour? Three minutes? 920 minutes?” For even though this may be the best Snow film since La Région Centrale in 1971 — a commemorative (and quite accessible) magnum opus with many echoes and aspects of his previous works — it enters a moviegoing climate distinctly different from the kind that greeted his earlier masterpieces. In 1969, the late, great Raymond Durgnat could find the same “mixture of despair and acquiescence” in both Frank Tashlin and Andy Warhol; today, on the other hand, avant-garde art is expected to perform like light entertainment.

Up to a point, Snow seems ready to oblige with his irrepressible jokiness —- a taste for rebus-style metaphors (often banal) and adolescent pranks (a giant penis hovering over a blonde’s backside) that makes this the least neurotic experimental film about technology imaginable — the precise opposite of Leslie Thornton’s feature-length cycle Peggy and Fred in Hell. Read more

M

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Fritz Lang

Written by Thea von Harbou, with Paul Falkenberg, Adolf Janesen, Karl Vash, and Lang

With Peter Lorre, Otto Wernicke, Gustaf Grundgens, Ellen Widman, Inge Landgut, Ernst Stahl-Nachbaur, Franz Stein, and Theodor Loos.

It’s unthinkable that a better movie will come along this year than Fritz Lang’s breathtaking M (1931), his first sound picture, showing this week in a beautifully, if only partially, restored version at the Music Box. (The original was 117 minutes, and this one is 105 — though until the invaluable restoration work of the Munich Film Archives, most of the available versions were only 98.) Shot in only six weeks, it’s the best of all serial-killer movies — a dubious thriller subgenre after Lang and three of his disciples, Jacques Tourneur (The Leopard Man, 1943), Alfred Hitchcock (Psycho, 1960), and Michael Powell (Peeping Tom, 1960), abandoned it. M is also a masterpiece structured with the kind of perfection that calls to mind both poetry and architecture and that makes even his disciples’ classics seem minor by comparison. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 19, 1997). — J.R.

Waco: The Rules of Engagement

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by William Gazecki

Written by Gazecki and Dan Gifford

Narrated by Gifford.

At some point in the middle of Dog Day Afternoon (1975) Sonny Wortzik (Al Pacino at his best) — a small-time operator and bisexual who’s taken over a bank to finance his male lover’s sex-change operation — has to step outside to bargain with the police. When it becomes clear that the crowd of bystanders and media that has gathered is more sympathetic to him than to the armed police, he calls out “Attica!” as a gesture of solidarity with the crowd and against the forces of law and order, which wins him more acclamation.

It’s a moment I recalled while thinking about the veiled allusion to the conflagration at Waco made by Timothy McVeigh on the day he was sentenced. This wasn’t because McVeigh, who has none of Wortzik’s charisma, qualifies as any sort of populist hero. It was because the fact that there can be no equivalence between the Waco disaster and the Oklahoma City bombing was apparently lost on McVeigh, just as the fact that there could be no equivalence between the slaughter of Attica prisoners in 1971 and robbing a bank was apparently lost on Wortzik — not to mention the crowd he was addressing. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 11, 1995). — J.R.

The Day the Sun Turned Cold

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Yim Ho

With Siqin Gowa, Tuo Zhong Hua, Ma Jing Wu, Wai Zhi, Shu Zhong, and Li Hu.

A striking moment in Mina Shum’s Double Happiness — a recent Canadian feature about an aspiring young actress in a North American city — reveals something about our attitudes toward Chinese culture. The Chinese-American heroine is auditioning for a small part as a waitress in a TV movie. After she runs through her lines, her prospective employers ask how good she is with accents. Pretty good, she replies; at this point we’ve already heard her southern drawl, and now she asks them in a French accent what kind of accent they want — French, perhaps, or something else? There’s a long, embarrassed silence, until she figures out that they want her to speak with a Chinese accent. She promptly does so, and with the same exaggeration she’d given her Southern Belle and Basic Frog. She immediately gets the part.

When Chinese movies audition for release in the North American market, I’m afraid the same sort of unspoken rules apply. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 18, 1991). — J.R.

THE GODFATHER PART III

*** (A must-see)

Directed By Francis Ford Coppola

Written by Mario Puzo and Coppola

With Al Pacino, Andy Garcia, Sofia Coppola, Eli Wallach, Talia Shire, Diane Keaton, and Joe Mantegna.

Let’s agree from the outset that the conclusion of the Godfather trilogy is not giving audiences everything that they expected based on the two previous installments. Shorter at 160 minutes than either of the first two parts, it proceeds in fits and starts, without the sustained narrative sweep of the first or the comprehensive historical spread of the second. Overall, there is less of a continuous story line (and less lucidity, coherence, and conviction regarding what plot there is), less violence, and less dramatic conflict; the quality of the performances is more variable; the settings are less memorable. There are even moments of risible implausibility. (Suffering insulin shock while visiting Cardinal Lamberto in a garden, Michael Corleone requests something sweet, and a pitcher of orange juice appears within seconds; and the virtuoso climactic sequence at the opera ultimately strains credibility by drawing together too many events at once.)

But conceptually and morally, one can argue that The Godfather Part III is superior to the two films in the Corleone family saga that preceded it. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 16, 1988). — J.R.

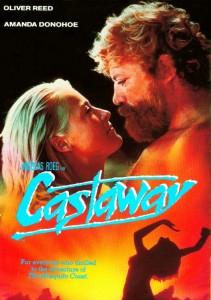

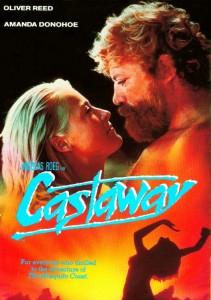

CASTAWAY

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Nicolas Roeg

Written by Allan Scott

With Oliver Reed and Amanda Donohue.

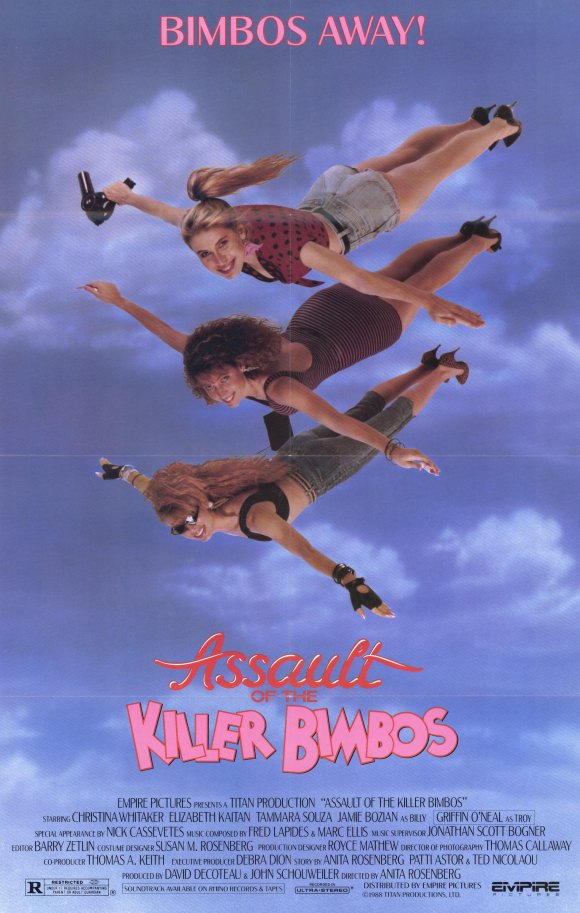

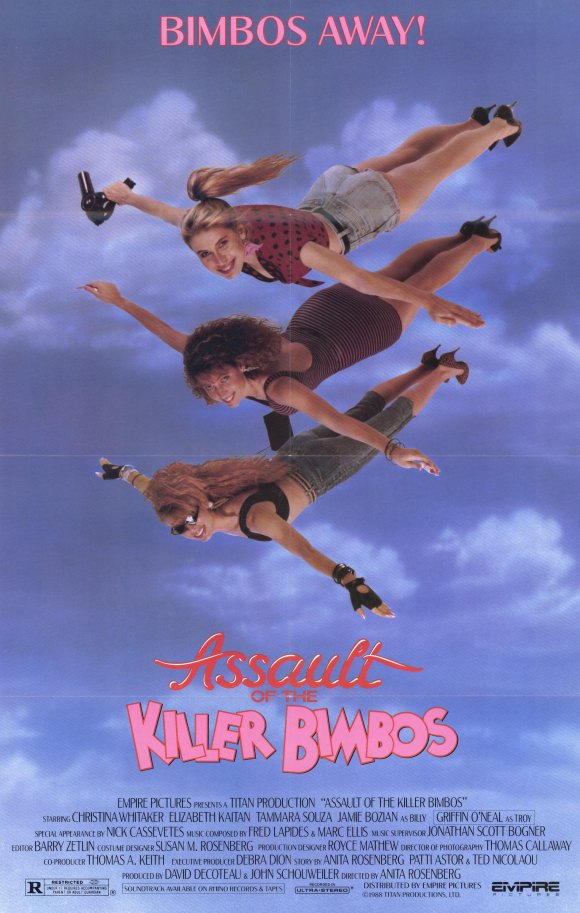

ASSAULT OF THE KILLER BIMBOS

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Anita Rosenberg

Written by Ted Nicoleau, Rosenberg, and Patti Astor

With Christina Whitaker, Elizabeth Kaitan, Tammara Souza, Mike Muscat, Nick Cassavetes, Dave Marsh, and Patti Astor.

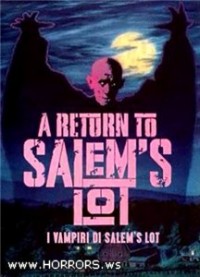

A RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Larry Cohen

Written by Cohen and James Dixon

With Michael Moriarty, Samuel Fuller, Andrew Duggan , Ricky Addison Reed, June Havoc, Evelyn Keyes, and Ronee Blakley.

The three movies listed above are all probably playing in Chicago this week, but not in any local theaters; they’re available in video rental stores and playing on home screens. Recent releases that have never opened theatrically, and presumably never will, they represent a growing breed of movie, at once omnipresent and unacknowledged.

Ever since the fairly recent time when the amount of money spent in this country on video rentals began to exceed the amount spent on movie tickets, notions about moviegoing have become even more specialized and limited. In contrast to moviegoing in the 20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s, when individual movies provided national experiences that were public and shared, moviegoing in the 60s, 70s, and 80s has increasingly become a less communal activity.

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 20, 1996). — J.R.

Ghosts of Mississippi

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Rob Reiner

Written by Lewis Colick

With Alec Baldwin, James Woods, Whoopi Goldberg, Diane Ladd, Bonnie Bartlett, Bill Cobbs, William H. Macy, Virginia Madsen, and Michael O’Keefe.

The Crucible

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Nicholas Hytner

Written by Arthur Miller

With Daniel Day-Lewis, Winona Ryder, Paul Scofield, Joan Allen, Bruce Davison, Rob Campbell, Jeffrey Jones, Peter Vaughan, and Karron Graves.

“This story is true,” reads the opening title of Ghosts of Mississippi, a movie about the murder of NAACP activist Medgar Evers in Jackson, Mississippi, in June 1963, and the conviction of his murderer, Byron De La Beckwith, which took a little more than 30 years.

“This play is not history in the sense in which the word is used by the academic historian,” Arthur Miller wrote in a note prefacing his 1953 play The Crucible, which depicts events that occurred in 1692, and which has now been turned into a movie adapted by Miller. Miller went on to detail the ways he’d changed history — he sometimes fused many people into one character, and he made a central character, Abigail, older. Read more

Written for the magazine Forum and published there in 1984. If I still have the published version, which would pinpoint the particular month and issue, I can’t locate it (although based on a tip from Barry Scott Moore, I think it may have been the February issue). For better and for worse, this is probably the most popular item on this site. — J.R.

The white morning sunlight, intensely brilliant, radiates through the open window as he sits propped up with pillows. She, also naked, sits quietly in his lap, her legs folded neatly under her, facing and kissing him with little pecks through her loose and undulating tangle of hair, both of them intermittently moaning with contentment. The two of them are fucking — or so it seems. The movie is An Officer and a Gentleman. They’re in a motel bedroom. He’s an air force officer trainee named Zack Mayo, played by Richard Gere. She is Paula, his girlfriend who works at the local paper mill, played by Debra Winger. As Pauline Kael aptly describes her, she sports “the world’s most expressive upper lip (it’s almost prehensile),” which “tells you that she’s hungrily sensual.” (A couple of years back, gleefully astride a wild, mechanical bucking bronco in Urban Cowboy, her sensual greed was no less apparent.) Read more

From Movieline (April 21, 1989, Vol. V, issue 99). — J.R.

It is a strange, grim tale, not typical of 1920s Hollywood entertainment.A gentle, burly dentist from the California mines named McTeague (Gibson Gowland) moves to San Francisco, where he befriends Marcus (Jean Hersholt), who works at the local dog hospital, and falls in love with Trina (Zasu Pittts), Marcus’s cousin and prospective fiancée. Out of friendship, Marcus relinquishes all claims on Trina, who gets engaged to “Mac”. But when she wins $5,000 in a lottery, Marcus feels cheated, and ruins Mac’s career by revealing that he has been pulling teeth without a license. After her marriage, the shy and frigid Trina becomes obsessed with the money she has won, refusing to spend any of it, and driving the impoverished Mac to drink and eventually to violence and murder….

Perhaps the least glamorous movie ever to have come out of a major studio, Greed (1924) is more than just a polemic about the power of money to destroy love and friendship. Finally appearing on video 65 years after its commercial release, it remains one of the most powerful of all silent movies, as well as one of the most modern in style and substance. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 16, 1990). This film has recently come out on Blu-Ray. — J.R.

JACOB’S LADDER

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Adrian Lyne

Written by Bruce Joel Rubin

With Tim Robbins, Elizabeth Pena, Danny Aiello, Matt Craven, Pruitt Taylor Vince, Jason Alexander, and Patricia Kalember.

“Around twenty-four hundred years ago Chuang Tzu dreamed that he was a butterfly and when he awakened he did not know if he was a man who had dreamed he was a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming he was a man.” The sense of metaphysical free-fall conveyed in this sentence from Jorge Luis Borges’s great essay “A New Refutation of Time” is like the disorientation one feels after watching a gripping and involving movie — a movie like Jacob’s Ladder, for instance. Like Chuang Tzu, one isn’t quite sure whether one has just left a dream, just entered one, or embarked on some magical if unsettling combination of the two. I tend to be partial to movies that traffic in these systematic displacements of reality — starting with Alain Resnais and Alain Robbe-Grillet’s masterpiece Last Year at Marienbad (1962), the locus classicus of this genre, continuing through much less radical examples like Fellini’s 8 1/2 (1963), and extending even to minor forays like last summer’s Total Recall. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 20, 1989). — J.R.

DANGEROUS LIAISONS

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Stephen Frears

Written by Christopher Hampton

With Glenn Close, John Malkovich, Michelle Pfeiffer, Swoosie Kurtz, Keanu Reeves, Mildred Natwick, and Uma Thurman.

Choderlos de Laclos’ Les liaisons dangereuses, first published more than 200 years ago, is one of the greatest novels ever written, but one would never guess it from the watchable but shallow comedy-melodrama of manners that Christopher Hampton and Stephen Frears have extracted from it. They’ve stuck fairly close to the general outlines of the original plot, but they’ve jettisoned the form entirely, so that what remains is a distortion as well as a simplification of what is conceivably the best French novel of the 18th century.

Admittedly, Roger Vadim’s updated French film adaptation of 30 years ago, set partially at a contemporary ski resort, was no less reductive, and a third film version presently being prepared by Milos Forman, Valmont, is unlikely to avoid similar problems. Laclos’ 1782 masterpiece is an epistolary novel consisting of 175 letters written by at least ten separate characters, preceded by a “Publisher’s Note” and an “Editor’s Preface” and accompanied by several “editorial” footnotes throughout — an intricate dialectical construction that offers us several independent and often contradictory versions of practically everything that happens, and more than one interpretation of what all the various events mean. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 7, 1990). — J.R.

THE RAGGEDY RAWNEY

*** ( A must-see)

Directed by Bob Hoskins

Written by Hoskins and Nicole De Wilde

With Dexter Fletcher, Hoskins, Zoe Nathenson, Dave Hill, Ian Dury, and Zoe Wanamaker.

An offbeat and highly original English film that’s been very slow making the rounds — Bob Hoskins’s The Raggedy Rawney (1987) — may be in trouble commercially. It didn’t even show in England until about two years after its completion, and it took an additional year to reach Chicago. Now that it’s here, it has at least five serious handicaps:

(1) At first glance, hardly anyone has any idea what the title means. (“Rawney,” a rather specialized word not found in most dictionaries, roughly means “magical madwoman.”)

(2) As an actor, Hoskins is basically known for his roles in contemporary settings, usually within a noir context — either as a gangster (as in The Long Good Friday and Mona Lisa) or as a detective (as in Who Framed Roger Rabbit). His part in The Raggedy Rawney, as a sort of gypsy leader, plays off neither of these associations, nor is it the lead role.

(3) Inspired by a legend told to Hoskins as a child by his grandmother that reportedly can be traced all the way back to the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1443), the movie is nonetheless given a setting so vaguely defined that the best description I’ve seen yet (published in the synopsis in Monthly Film Bulletin) is: “Sometime during the first half of the 20th century, in a European country at war.” Read more