From Monthly Film Bulletin, July 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 510). –- J.R.

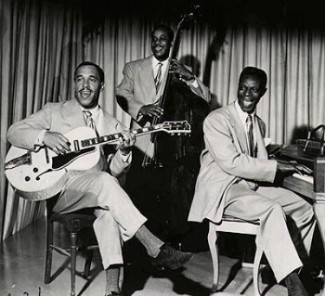

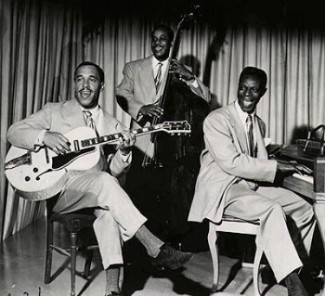

Nat King Cole Trio

U.S.A., 1948

Director: Josh Binney

Dist—TCB. p.c–All-American. p–Glucksman. m/songs–“Oo Kickerooni”, Rooney”, ‘”Now He Tells Me”, “Breezy and the Bass” performed by–Nat “King” Cole (piano, vocals), Johnny Miller (bass), Oscar Moore (guitar). No further credits available. 262ft. 7 mins. (16 mm.).

A musical extract from the Forties black feature Killer Diller — made, like Jivin in Be-bop, exclusively for black audiences — this short illustrates Cole’s remarkable piano playing in a concert, as well as certain aspects of the cooler and more commercial vocal style which he eventually adopted. A graceful, inventive soloist, whose style virtually bridges swing and bebop, with long, perfectly articulated lines which have influenced pianists for three successive decades, he also conveys an unmistakable stage presence — sitting almost perpendicular to the piano while performing difficult runs effortlessly in a manner that is nearly as ‘visual’ as Chico Marx’s. Moore and Miller also takes solos, and the latter is highlighted on “Breezy and the Bass”, a fast virtuoso piece based on the chords of “I Got Rhythm”; “Now He Tells Me” features Cole’s smooth mock-hip singing of the period, exuding a kind of throwaway charm that remains irresistible.

From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1977 (Vol. Read more

From the July 1980 issue of Omni. Portions of this are derived from a lecture I gave at the Venice film festival the previous year, which is reprinted in my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980). A lot of the terminology used here seems pretty quaint now. — J.R.

Speculating on what movies of the future will be like, it’s hard to get very far without some notion of the changing needs of the audience. A crucial part of this change can be detected in where we see movies. According to present signs, it seems pretty clear that most of the films we’ll see will be either in homes or in shopping malls.

“Once inside a mall, shoppers have few decisions to make,” the magazine Dollars & Sense recently noted. “Corners are kept to a minimum so the customers will flow along from store to store, propelled, as the developers say, by `retail energy’.” It’s a description that fits several recent movie blockbusters — and others we can expect to see in the future.

By contrast, the movie houses that traditionally cropped up near the centers of towns — public gathering places, not unlike the municipal squares they were often adjacent to — are quickly becoming nostalgic emblems of another era. Read more

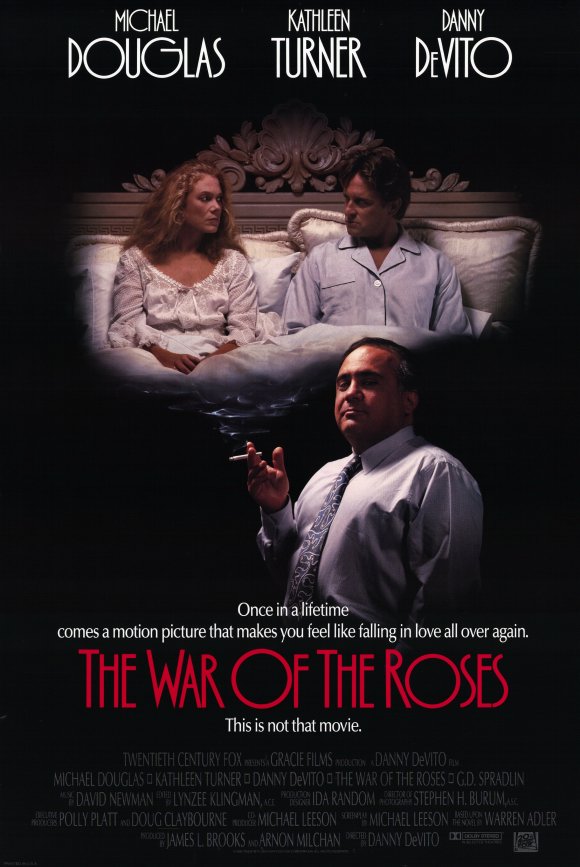

From the Chicago Reader (December 15, 1989). — J.R.

THE WAR OF THE ROSES

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Danny DeVito

Written by Michael Leeson

With Michael Douglas, Kathleen Turner, DeVito, Marianne Sagebrecht, Sean Astin, and Heather Fairfield.

The proper tone for Danny DeVito’s second feature is set by a very short Matt Groening cartoon that precedes every print. A brief cadenza on familial hatred and violence is played out in a therapist’s office, where most of the hatred and violence is directed at the therapist, uniting the family in the process. The War of the Roses opens with another sort of therapist — Danny DeVito as high-priced lawyer Gavin D’Amato — talking to a client in his office. The landscape outside D’Amato’s office looks unusually fake, and DeVito’s delivery seems as self-consciously overarticulated as some of Woody Allen’s recent performances — to mix a metaphor, one can almost see the chalk marks in his verbal punctuation — but both of these oddities actually serve the story he is about to tell about a marriage and its demise.

Unlike the therapist in the Groening cartoon, D’Amato stands mostly outside the story he is telling, and he clearly represents the voice of reason rather than part of the problem. Read more