From the Chicago Reader (July 15, 1994). — J.R.

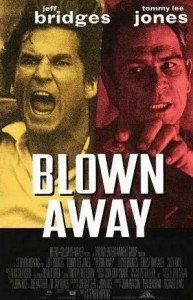

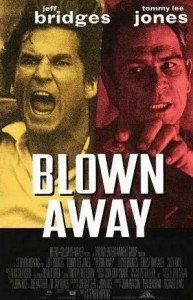

* BLOWN AWAY

(Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Stephen Hopkins

Written by Joe Batteer, John Rice, and M. Jay Roach

With Jeff Bridges, Tommy Lee Jones, Lloyd Bridges, Forest Whitaker, Suzy Amis, John Finn, and Stephi Lineburg.

In the Roy Rogers westerns I saw as a kid, I could always figure out in a flash who the villain was. If memory serves, Roy Rogers always played a cowboy named Roy Rogers, whom the good characters invariably called Roy and the bad guy referred to as Rogers. This sometimes made it possible to know who the bad guy was even before Roy figured it out himself.

There’s a popular kind of suspense movie that’s been with us at least since Dirty Harry in which the villain is often just as easy to detect: he or she is someone who has it in for the hero and wants to hurt him very, very badly, most often by hurting or killing whomever the hero is supposed to protect: his daughter’s pet rabbit (Fatal Attraction), his wife, his mistress, and his daughter (Cape Fear), the citizens of Gotham City (the Batman movies), the president of the United States (In the Line of Fire), the passengers in a local bus (Speed), a coworker and a pet dog and a wife and a daughter (Blown Away). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 3, 1994). — J.R.

** LITTLE BUDDHA

(Worth seeing)

Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci

Written by Mark Peploe, Rudy Wurlitzer, and Bertolucci

With Keanu Reeves, Chris Isaak, Bridget Fonda, Alex Wiesendanger, Ying Ruocheng, Jigme Kunsang, Raju Ial, and Greishma Makar Singh.

“Nirvana” is a word that comes from Sanskrit, the Reader’s Encyclopedia informs me, meaning “blowing out, extinction”; in Buddhist teaching it refers to “a complete annihilation of the 3 main ego-drives, for money, fame, and immortality.”

Bernardo Bertolucci has said that his aim in Little Buddha is low-key. Of the third film in his self-described orientalist trilogy, following The Last Emperor (1987) and The Sheltering Sky (1990), he says, “My hope is to open the eyes for a glimpse of something, my hope is to trigger a curiosity about something. I can’t teach or ask anything more than just for others to participate in my emotional discovery of Buddhism.” But Little Buddha is a multimillion-dollar project designed to make money and to exploit and perpetuate Bertolucci’s fame while catering to the viewer’s desire for immortality. So it shouldn’t come as any surprise that nirvana, one of the cornerstones of Buddhist thought, plays a reduced role in Bertolucci’s “emotional discovery,” whereas reincarnation as a means of immortality plays a major role. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 4, 1990). — J.R.

DOCUMENTING THE DIRECTOR

It’s no secret that over the past few years, while “entertainment news,” bite-size reviews, and other forms of promotion in all the media have been steadily expanding, serious film criticism in print become an increasingly scarce. (I’m not including academic film interpretation, a burgeoning if relatively sealed-off field that has by now developed a rhetoric and a tradition of its own — the principal focus of David Bordwell’s fascinating book Making Meaning, published last year.) But the existence of serious film commentary on film, while seldom discussed as an autonomous entity, has been steadily growing, in some cases supplanting the sort of work that used to appear only in print.

There are plenty of talking-head “documentaries” about current features — actually extended promos financed by the studios — currently clogging cable TV, but what I have in mind is something quite different: analytic films about films and filmmakers. Many of these films are shown in film festivals, turn up on TV, and are used in academic film courses, but very few of them ever wind up in commercial theaters, with the consequence that they’re rarely reviewed outside of trade journals. Read more