From The Movie No. 82 (1981). — J.R.

The war in Vietnam created in the United States a national trauma unparalleled since the Civil War, and its after-effects may prove to be every bit as enduring in the American consciousness. It was a war fought not only with guns and napalm in Southeast Asia, but with placards and truncheons on campuses and streets in large cities throughout the western world. It became the largest, most crucial issue of a generation — virtually taking over such related matters as black protest and the youth-drug subculture — but Hollywood was afraid to deal directly with it, even on a simple level.

Hollywood has traditionally done its best to avoid contemporary politics and especially political con troversy, largely for commercial reasons. There is always the danger that a shift in public opinions or interest, between the time of a film’s production and its release date, may render a film with a ‘timely’ subject unmarketable in the long run, or sooner; and few producers are ever willing to take such a risk. The profound divisions created by the Vietnam War in American life were too wide, in a sense, to be commercially exploitable — at least while America remained actively involved. Any treatment of the issue was bound to exclude or alienate too large a section of the potential audience.

This happened with The Green Berets (1968), co-directed by and starring John Wayne — the only large-scale, simple-minded war film about Vietnam financed by a major Hollywood company. But even this rather old-fashioned, flag-waving action film saw fit to Include a skeptical journalist with dove-like leanings among its otherwise hawkish characters, as an unbeliever who has to be converted by John Wayne’s Colonel Kirby.

As it turns out, this conversion is largely a matter of acknowledging the unlimited savagery of the Vietnamese Communists — the same sort of racial type-casting often assigned to the Japanese in Hollywood films made during World War II and to the North Koreans during the Korean War. If any major lesson can be extracted from The Green Berets, it is that the mythical, heroic archetypes of Ameri can soldiers promulgated by Wayne and others during World War II and Korea were no longer as viable or as believable in the late Sixties, even to right-wing patriots.

At the same time, the subject of Vietnam, while seldom confronted directly elsewhere and most often relegated to the background, represented an important undercurrent in many films made during the period.It soon became an inseparable part of the conflicts and considerations that were being dealt with in most youth films. The cultural and gener ational conflicts of The Graduate (1967), Easy Rider and Alice’s Restaurant (both 1969), the campus revolts of Getting Straight and The Strawberry State ment, the heightened visions of utopia in Woodstock and of apocalypse in Zabriskie Point (all 1970), had reference to, and association with, the war. Even an artist as seemingly apolitical as Ingmar Bergman could scarcely avoid making a comment on the war in a film such as Persona (1966), when he showed Elisabeth Vogler (Liv Ullmann) watching the self-immolation of a Buddhist monk in South Vietnam on television, and recoiling in agony — in effect, invaded by the deepest suffering in the modern world.

The fact that American viewers could watch the Vietnam War every day on television tended to blunt its impact — a telling aspect of a movie about private domestic violence such as Petulia (1968), where the war is perpetually visible on diverse television screens, yet remains rigorously unmen tioned and undiscussed by the characters. The notion of an uncontainable horror eventually pro duced absurdist, black-humour treatments of modern warfare that conveniently concerned themselves with earlier wars, such as World War II in Catch-22 and Korea in M*A*S*H (both 1970).

Still another way of approaching the subject obliquely was through the historical allegory pro vided by the Western. Within these terms, the meditative, slow-motion look at the massive slaugh ters in The Wild Bunch (19691 and the tortured examination of the mutual barbarism of Apaches and whites in Ulzana’s Raid (1972i could both address themselves to the war’s wider issues and emotional conflicts.

in all these instances, a certain ambiguity in the film-makers’ approaches allowed them to address hawks and doves alike. But it was not until the late Seventies that the subject of Vietnam was finally tackled head-on — after a fashion — by the film industry. And even then, the chief response was to dodge central facts about the war for the sake of additional myths and allegories, many of which seemed designed to reinterpret painful recent his tory in a more positive light — whether as therapy or as alibi, a rationalization or an avoidance of the immediate past.

Perhaps by the Nineties a sufficient time gap will have elapsed to allow filmmakers to approach the subject of Vietnam in a more detached, balanced and analytical manner. In the meantime, The Deer Hunter (1978) and Apocalypse Now (1979) both fall into an unavoidable trap. They offer mythical and metaphysical meanings about the war which seem inevitably tailored to the short-term psychic needs of an American or American-influenced audience –- namely, the desire to locate the horror of the war within a containable image of externalized evil rather than to look at it as the consequence and function of internal ideological processes. As the American journalist Deirdre English succinctly puts it, each film “takes a fabricated act of Vietnamese terror” — the ultra-sadistic Russian roulette game of The Deer Hunter, the hacking off of inoculated children’s arms in Apocalypse Now – “and elevates it to become the central metaphor of the war”.

In fact, the evasions about Vietnam in the two films work within very different contexts, though the end results may be similar in some ways. For one thing. The Deer Hunter operates within a mythic system in which “the war” is merely an episode, though a crucial one, in a larger structure en compassing the lives of several men — a sort of trial by fire which destroys or seriously marks all of them, but which is given little or no independent significance. In other words, the mere fact that the war functions dramatically as something external to the characters played by Robert De Niro and Christopher Walken — something that happens to them rather than because of them, or with their complicity — ensures that the Vietnamese Commun ist torturers absorb the metaphysical weight of impersonal evil that they are structured to embody.

Despite the childlike naivety of the filmmakers and the characters alike, many liberal American critics defended the film on the basis that it was myopic to assume that the Vietnamese Communists did not commit atrocities along with the Americans. At the same time, this naivety allowed the film to function dramatically in old-fashioned terms, with some of the mythic resonance of a John Ford Western — succeeding precisely where The Green Berets had failed, because the dramatic needs (which included a feeling for small-town, com munal ties) appeared to structure this view of the war rather than the other way round.

In the case of Apocalypse Now, the ideological cast seems at once more conscious and more deceptive. Designed and assembled more as an environmental entertainment complex — a ‘trip’ in every sense of the word — than as a unified drama, the film manages to incorporate a surprising number of mythical and metaphorical ideas to support several positions regarding the war, some of them quite opposed to one another. It can be said without exaggeration that hawks, doves, and those in between can all find their beliefs confirmed in the film. This indeed seems reflected in the layered manner in which the film was constructed, with John Milius’s fanciful right-wing adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s anti-colonialist novella Heart of Darkness complicated, in turn, by Francis Ford Coppola’s preoccupations with megalomania and Michael Herr’s cynical narration, some of It virtu ally adapted from his memorable book Dispatches. which mixed personal combat reporting with a sort of lyrical, liberal-humanist rock poetry

Within such a network of cross-currents anti counter-forces, the Jungian archetype provided by Colonel Kurtz (Marion Brando) — representing the dark side of the self driven towards evil, eventually becoming Evil incarnate — operates more as a focal point for the audience’s self-absorption than as a lens trained on America’s involvement in Vietnam. More actively myth-creating than The Deer Hunter, Apocalypse Now is clearly more cognizant of the possibilities of American guilt regarding the war. Yet in Kurtz’s climactic speech about the di memberment of inoculated children — a detail which can be traced back to Milius’s original script — this knowledge capitulates once again to the image of the Vietnamese Communists as ineffably savage.

By 1976, the war was over, the soldiers were home and Nixon had resigned from office in disgrace. More than one commentator had suggested that the Watergate scandal provided A meri cans with a scapegoat for the traumas occasioned by the American involvement in Vietnam. The sense of national shame was somewhat alleviated by the bicentennial celebrations.

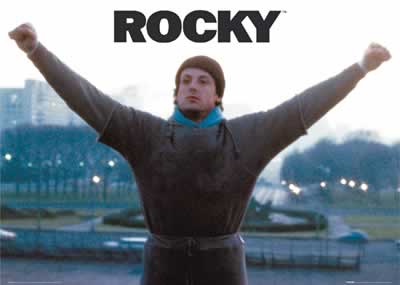

Then, out of nowhere — and in true all-American spirit — actor and novice scriptwriter Sylvester Stallone parlayed a $1 million movie into one of the top 20 all-time moneymakers by creating the boxing film Rocky (1976 ). The ‘Italian Stallion’, a white sub-proletarian regular loser — a figure recalling early Paddy Chayefsky heroes like Ernest Borgnine in Marty (1955) — thumbs his nose at a society that could not care less about him, and finds both love and self-respect in a corrupt world. Responding to the fairy-tale quality of this modern-day romance — and, perhaps, to the racial subtext (poor, dispossessed white man triumphing over his ghetto existence and getting his own back on de-ghettoized uppity blacks) — audiences stood up and cheered.

Saturday Night Fever (1977) offered a variation on this theme. Its teenage hero, played by John Travolta, is no less a denizen of an Italian ghetto, an Al Pacino fan with a poster of Stallone in his bedroom. Living in Brooklyn, he is separated by more than just a bridge from the glamour of Manhattan. Identified from the very start of the movie with a ‘body language’ that reflects black culture. Travolta’s Tony Manero paradoxically represents the desire to break beyond the ghetto’s confinement at the same time that his godlike manifestation on a disco dance floor suggests a precise form of cultural containment.

Another loser-hero of the time was Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), a Vietnam veteran who takes to driving a cab in Taxi Driver (1976) and murmuring murderous thoughts about New York being an open sewer. The racist underpinnings of Bickle’s alienated, homicidal hatreds are deflected by the film’s ingeniously deceptive strategies so that his potential targets become, in turn, a nondescript political candidate and a teenage whore’s pimps and clients. He only poses an unsuccessful threat to the candidate but he actually destroys the pimps and a client.

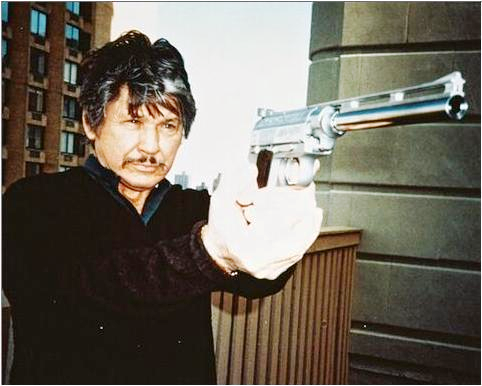

Certainly a more equivocal hero than Rocky, Travis Bickle is nevertheless accorded a dreamlike ascension to power and acceptance by the film in a manner that smacks no less of fanciful wish-fuIfillment. Audiences did not stand up and cheer his bloody devastation, as they had previously cheered the vengeful vigilante played by Charles Bronson in Death Wish (19741, possibly because some of the details – fingers shot off, blood splattered on walls. arterial spurtings — were at once too shocking and too suggestive of certain American atnxities in Vietnam, such as the My Lai massacre.

The film concludes with Bickle praised in the press for his deeds and finally respected by the woman of his dreams (Cybill Shepherd), This was an ending that granted the Vietnam veteran a heroic standing in his community that the real world outside the movie theatre denied him. John W. Hinckley, Jr. was too young to have been a Vietnam veteran but perhaps he still bore traces of Its violent legacy and certainly he was enamoured with the screen image of Jodie Foster, who played the teenage whore in Taxi Driver. Only five years alter the film, he made his own bid for fame, and her attention, by shooting President Ronald Reagan in an assassination attempt.

JONATHN ROSENBAUM