From the Chicago Reader (September 5, 2003). — J.R.

September 11

*** (A must-see)

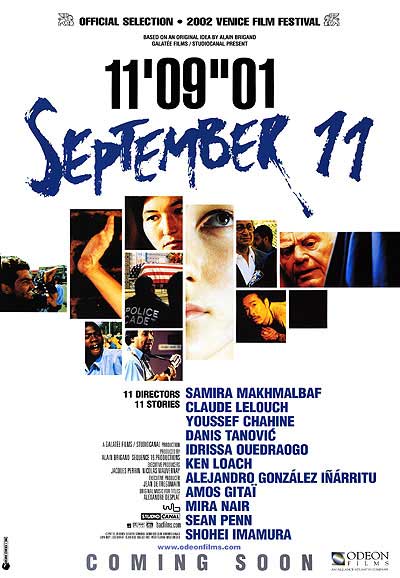

Directed by Samira Makhmalbaf, Claude Lelouch, Youssef Chahine, Danis Tanovic, Idrissa Ouedraogo, Ken Loach, Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu, Amos Gitai, Mira Nair, Sean Penn, and Shohei Imamura

Written by Makhmalbaf, Lelouch Chahine, Tanovic, Ouedraogo, Paul Laverty, Vladimir Vega, Gonzalez Inarritu, Gitai, Marejos Sanselme, Sabrina Shawan, Penn, and Daisuke Tengan.

It was probably inevitable that the terrorist attacks of September 11 were immediately seen as a blow against America rather than as crimes committed against humanity, the world community, or even just the people, many of whom were not American, who happened to be occupying three particular buildings. We deduced from the reported beliefs and intentions of the terrorists that America and what it represented to them was the desired target. But the willingness to privilege this vision over every other possible understanding of the tragedy may be dangerous. It even suggests a certain ideological defeat, because it has allowed the enemy to set the terms of the conflict.

The reflex is understandable. “Humanity” and “world community” are abstract. “America” is also abstract but feels closer to home. Because it’s familiar, it’s treated as if it were the only reality, as if it were, in fact, the world. This is certainly the attitude of the current Bush administration, and it has consequences quite separate from the losses of September 11 that extend well beyond the privileging of American interests.

For this reason, September 11 — a feature consisting of 11 11-minute responses from around the world to the tragedy of September 11, originally called 11’09″01 — is indispensable. It premiered a year ago in at least 15 other countries, and the delay in showing it in this country — it opens this weekend at the Music Box — might be explained by what some critics have labeled its anti-Americanism.

Four segments do make arguments that are critical of American policies: Youssef Chahine’s episode mentions the training Osama bin Laden got from Americans; Shohei Imamura’s segment mentions “holy” wars, including our own; Ken Loach examines the brutal, CIA-led decimation of Salvador Allende’s government and 30,000 Chileans; and Mira Nair probes the bias that led to a young Pakistani and U.S. citizen who died saving lives at the World Trade Center initially being branded a terrorist when he was reported missing. Yet Chahine also critiques his own emotional confusion, and Imamura criticizes the Japanese army’s actions in World War II more directly than anything done by Americans or Islamists. Loach also mourns the American deaths on September 11, and Nair shows that the Pakistani victim’s coffin was draped in an American flag at his funeral. So calling these segments anti-American means ignoring at least half of what they’re saying.

It would be preposterous to claim that any film could encapsulate what the “rest of the world” thinks or feels about the September 11 attacks. This film has only 11 directors, and none of them could claim to represent any sort of consensus. It’s worth considering some of the other filmmakers who were approached about making a segment but whose contributions didn’t pan out. According to a story in Le monde, Giuseppe Tornatore planned a “requiem” with photographs of victims accompanied by Ennio Morricone’s music, and Abel Ferrara — who knew personally many of the firefighters who were killed and would have been the only New York participant — wanted to combine documentary footage with fictional reenactments; given Ferrara’s searing vision of evil in the modern world, this loss seems especially regrettable. Among the others approached were Robert De Niro, Roman Polanski, Regis Wargnier, and John Woo.

Nevertheless, I think this film takes a healthy step toward giving us a broad, enlightening survey. At the very least, it fulfills four of the five aims cited by Alain Brigand, the film’s producer and artistic director: “Evoke the sheer scale of the shock wave that followed September 11, testify to the resonance of the event throughout the world, better convey the human dimension of this tragedy, bring reflection to emotion, give a voice to all.” Only the last of these aims isn’t achieved, nor is it achievable. (Incidentally, this film’s antithesis will be on Showtime this Sunday, a fictionalized glorification of Bush’s romantic self-image entitled DC 9/11 that’s described by the Village Voice‘s J. Hoberman as “a shameless propaganda vehicle for our superstar president”; of course we’ve already been getting the same sort of material in TV news broadcasts.)

September 11 arrives at a time when many of us feel no safer than we did before the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. None of its reflections are out-of-date, and even those that seem wrongheaded expose us to relatively fresh viewpoints.

Brigand stipulated only that each episode be 11 minutes, 9 seconds, and one frame in length. He should be commended for ordering the results intelligently and for honoring the diversity through careful, balanced placement. My favorite segments are the first (by Samira Makhmalbaf, who’s from Iran), the fifth (by Idrissa Ouedraogo, from Burkina Faso), the sixth (by Loach, from England; he worked with writers Paul Laverty and Vladimir Vega), and the eleventh (by Imamura, from Japan; he worked with writer Daisuke Tengan). Each is powerful because it’s rooted in the particulars of another culture (also true of the fourth segment, by Danis Tanovic, a Bosnian, and of the eighth, by Amos Gitai, an Israeli; both have lesser strengths of their own). And each is placed in the position where it can have optimal impact, complementing rather than competing with the others.

Three of the sketches are allegories, two of them rather awkward and obscure — the second (by a Frenchman, Claude Lelouch) and the tenth (by an American, Sean Penn). Both are “poetic” love stories set in New York, centered on individuals who are unaware of the disaster: a deaf Frenchwoman in the Lelouch and a grieving American widower (Ernest Borgnine) in the Penn. Both include TV screens that show the attacks, but the protagonists are lost in their private reveries and never notice them.

Fortunately these episodes have been tucked away where they can do the least damage to the film as a whole. The third allegory is by Imamura, and he’s rightly accorded the last word, in a creepy tale about a Japanese soldier returning from the front believing he’s a snake. Significantly, this is the only episode that makes no mention of September 11, though it may have the most to say on the subject.

The most problematic episode for me — apart from the Chahine, with its scattershot ruminations, and the Penn, with its mawkish irrelevance, despite a good performance from Borgnine — is the most experimental, by Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu, the Mexican director of Amores perros. It begins potently as a complex sound mix over black leader chronicling the New York attacks with fragments of news reports, sound effects, and music periodically broken by almost subliminal flashes of falling bodies — a striking effort to make the unbearable perceivable by resensitizing us to sound and image. But this achievement is overtaken and contradicted at the end by the grandiosity of the symphonic music used and a translated Arabic sentence, “Does God’s light guide us or blind us?” Gitai’s episode, which is also about the confusion of sensory overload — the media hysteria following a September 11 terrorist explosion in Tel Aviv — seems compromised rather than enhanced by the filmic bravura of Gitai shooting it all in one take.

The Loach section, which demonstrates that there’s more than one September 11 to mourn, taught me the most. Equally important may be the lessons of Makhmalbaf, who was only about 21 when she shot her scene with Afghan refugee pupils, and Ouedraogo, working comically with young boys — about how remote the U.S. seems to children in Iran and Burkina Faso. How much can Afghan kids understand about the attack on the Twin Towers when they don’t even know what a tower is? And isn’t it only logical that a boy hoping to get a $25 million reward for capturing Osama bin Laden to pay his mother’s medical expenses would also consider kidnapping George Bush when his first scheme flounders?