My Afterword to the second edition (paperback) of my 2004 collection Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons. — J.R.

“Unwitting omissions —- films I’ll eventually hate myself for having overlooked — are inevitable,” I wrote in December 2003, introducing my list of 1,000 personal favorites, “largely because I haven’t come up with any sure-fire method of recalling or tabulating everything I’ve seen, or even everything I can remember seeing.” Even when I wrote this, I could scarcely imagine I’d omit a film as important as Chimes at Midnight (1966) from my list —- an oversight that illustrates my point all too well. No less vexing was the absence of Flaming Creatures(1963), a film celebrated elsewhere in the same book, and the silly blunder of renaming Crimson Gold (2003) Crimson Red — though at least I was able to correct these latter gaffes, as well as restore a missing accent to Tangos volés (2002), in the book’s second printing. (In the case of Flaming Creatures, this addition was managed ecologically by omitting The Disorderly Orderly [1964] from my list on the same page.)

I discovered the omission of Chimes at Midnight later, from a blog, while cruising the Internet. I also encountered some skeptical questions about why I hadn’t included more animated films on my list, or Fanny and Alexander (a film, I must confess, that I still haven’t seen) [2014: by now I have seen the feature-length digest, but not yet the full TV series] —- questions that can’t be answered except by reiterating and stressing the word “personal”.

How could I update such a list? Practically speaking, the option of adding and subtracting titles to create a somewhat different 1,000 for this book isn’t open to me. And it seems relatively unfruitful to list possible subtractions. But I’ve jotted down 26 titles of more recent films (2003-2007) —- preceded by 26 titles of more recent discoveries, rediscoveries, or acknowledged oversights of older films (1919-2001) —- that would qualify as contenders if I had such an option, which I’ll list chronologically:

Blind Husbands (Stroheim, 1919)

Diagonale Symphonie (Viking Eggeling, 1924)

King Kong (Merian C. Cooper & Ernest B. Schoedsack, 1933)

Jolly Fellows (Grigori Alexandrov, 1934)

Okraina/Outskirts (Boris Barnet, 1934)

Young Mr. Lincoln (Ford, 1939)

The Shanghai Gesture (Sternberg, 1941)

I Married a Witch (Clair, 1942)

La Nuit Fantastique (L’Herbier, 1942)

A Canterbury Tale (Powell/Pressburger, 1944)

Unfaithfully Yours (Sturges, 1948)

Late Chrysanthemums (Mikio Naruse, 1954)

Pete Kelly’s Blues (Jack Webb, 1955)

Calle mayor (Juan Antonio Bardem, 1956)

movie theater sequence from Don Quixote (unfinished film, Welles, 1957)

Komal Gandhar/E-Flat (Ghatak, 1961)

The Iranian Crown Jewels (Golestan, 1965)

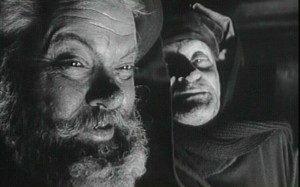

Chimes at Midnight (Welles, 1966)

Kiev Frescos (Paradjanov, 1966)

Army of Shadows (Melville, 1969)

Rendez-vous à Bray (André Delvaux, 1971)

Winter Soldier (collectively made, 1971)

The Other Side of the Wind (unfinished film,Welles, 1976)

Warsaw Bridge (Portabella, 1990)

Balkan Inventory (Gianikian & Lucci, 2000)

Porto of My Childhood (De Oliveira, 2001)

Coffee and Cigarettes (Jarmusch, 2003)

The Corporation (Mark Achbar & Jennifer Abbott, 2003)

Pas sur la bouche (Resnais, 2003)

The Saddest Music in the World (Maddin, 2003)

Before Sunset (Linklater, 2004)

Delamu (Tian, 2004)

Ten Skies (Benning, 2004)

The World (Jia, 2004)

Howl’s Moving Castle (Hayao Miyazaki, 2004)

The Power of Nightmares (Adam Curtis, 2004)

Star Spangled to Death (Jacobs, 2004)

Yes (Potter, 2004)

A History of Violence (Cronenberg, 2005)

Away from Her (Sarah Polley, 2006)

Bamako (Abderrahmane Sissako, 2006)

Black Book (Verhoeven, 2006)

Citadel (Egoyan, 2006)

Coeurs (Private Fears in Public Places) (Resnais, 2006)

The Dead Girl (Karen Moncrieff, 2006)

Find Me Guilty (Sidney Lumet, 2006)

Inland Empire (Lynch, 2006)

Offside (Panahi, 2006)

Opera Jawa (Garin Nugroho, 2006)

Still Life (Jia, 2006)

When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts (Lee, 2006)

Kramasha (To Be Continued) (Amit Dutta, 2007)

And for the 1980 version of The Big Red One (Fuller), I’d substitute the 2004 “reconstruction” of Richard Schickel, even though that term would be a misnomer in this case.

Other questions and demurrals remain, and I’m not sure how adequately I can respond to them. On the day after Christmas 2006, I received an email query from a film student, one Matthew Randall, asking why I’d included The Iceman Cometh by Clarence Fok. “The reason I’m asking is…the film stands out as the only martial arts piece in the list, and my slight distaste for it stems from the disturbing acts of misogyny [performed] by the villain, played by Yuen Wah. It is mentioned only in passing in your assessment of Maggie Cheung’s acting abilities in [your] article on Irma Vep. Do you find the film’s merit in the comical social critique that [arises from the time-traveling], the kung-fu swordplay, or some other factors?” He went on to suggest that if it was the former, Stanley Kwan’s Rouge did the job much better, and the late Anita Mui in that film was every bit as gifted as Maggie Cheung.

Most of which may be perfectly, or at least partially, true. (Randall conceded in a subsequent note that one other martial arts film figures on my list, Ashes of Time.) As it happens, I’ve seen Rouge, and remember it with some fondness as my second favorite Kwan film. Why then did I exclude it from my list in favor of The Iceman Cometh — which I saw on Australian TV about nine years later, and then only because critic Lesley Stern, who was living in Sydney at the time, invited me to watch it with her?

I don’t have an adequate answer to this question. Insofar as my selection of The Iceman Cometh does function as a token acknowledgement of martial arts movies, it’s completely useless as a critical statement, because I arrived at this title (as opposed to others I might have seen or acknowledged) strictly by chance, and I can’t even recall my responses in any detail. So the vagaries of memory and a few gut instincts regarding the list’s overall range and balance can’t be ruled out as determining factors. Initial impressions play an important role as well: writing in London’s Time Out in 1974, I expressed a preference for F for Fake over Chimes at Midnight — a bias I’ve recently tried to gloss in my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles, and one which suggests at least one possible unconscious reason why it didn’t surface on my list in late 2003.

I’m certain that I can’t account for all the other factors at play in my selections. Speculation about some of these factors figured in an online interview that filmmaker Kevin Lee and a few others conducted with me in 2004, as in the following exchange:

Question: Those of us who suspect you are biased against mass-appeal favorites could forgive the exclusion of Gone with the Wind or Star Wars, but Casablanca??? Is Casablanca missing from the list because you consider it too status-quo? How would you account for why many movie fans love it? Do you consider love for Casablanca to be an example of herd mentality, or is its non-inclusion on the list simply an example of your being provocative and iconoclastic? Or is it we who are reading too much into this? ….Same question about King Kong.

Answer: I do like Casablanca — if its status is part of some herd mentality, then I’m part of that herd. It just isn’t one of my 1000 favorite films. I actually like Gone with the Wind even more than Casablanca, and King Kongmore than Gone with the Wind. In fact, King Kong was originally on my list, and I can no longer remember now why I bumped it. I must have thought of some other film I liked more….I’ve always detested Star Wars and this was never in the running. (1)

More recently, Cindi Rowell of New Yorker Films has directed me to another list —- “The 1,000 Greatest Films as voted by 1,320 critics, reviewers, scholars, filmmakers and other likely film types” —- at a web site called “They Shoot Pictures, Don’t They?”, a list most recently compiled in December 2006. (2) Here one can also access “TSPDT’s ‘Greatest 1,000 Films’ grouped by All-Movie Guide genres, keywords, themes and tones” (3), a 276-page compendium. The latter has been prepared as a guide for selecting films from the 1,000 “to best suit your mood at any given time,” noting that “In many cases, TSPDT disagrees with the [categories] that the All-Movie Guide has allocated for a given film.”

If, indeed, you’re wondering, as I was, how such highly interpretive readings of these categories are played out, I can convey a few facts I’ve compiled on my own. “Genres,” stretching alphabetically from “abstract film” (five titles) to “world history” (just one title, Shoah), consume 40 pages. “Keywords,” proceeding from “abandon” (eight titles) and “ABC-News” (just one title, Breathless) to “zombie” (four titles, including Eraserhead), cover 146 pages. “Style,” not included in the above summary, stretches from “allegory” (quite a few) to “TV miniseries” (just the Decalogue and Heimat), and takes up only two pages. “Theme,” from “actor’s life” (22 films) to “zombies” (three films, excluding Eraserhead), covers 30 pages. And finally, “tone,” going all the way from “affectionate” to “wry” (plenty of each, but more of the latter) covers 56 pages.

If you’re also wondering, like me, how “world history” functions as a genre that Shoah belongs to, or what the keyword “ABC-News” has to do with Breathless, or who the zombie (singular) might be in Eraserhead, one should also admit that some of the other categories may prove to be useful research tools (though hopefully not for term papers). More importantly, even though a certain delirium of systematizing seems to characterize such efforts, they still testify to the vitality and utility of list-making during a period in which the bounty of films becoming available on DVD has become both exciting and more than a little daunting.

J.R.

Notes

- alsolikelife.com/FilmDiary/rosenbaum.html

- theyshootpictures.com/gf1000.htm

- theyshootpictures.com/Top1000Films_AMG%20Breakdown.pdf