This was written in the mid-1970s for Cinema: A Critical Dictionary, a two-volume reference work edited by Richard Roud that wasn’t published until 1980 (by The Viking Press in the U.S. and Secker & Warburg in the U.K.), and reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema. — J.R.

Otto Preminger (born 1906) directed five films before Laura (1944) — one Austrian, four American — but since he disowns them, I haven’t seen them, and no commentator to my knowledge has ever spoken well of them, we might as well begin with the (false) assumption that a tabula rasa preceded his early masterpiece.

False assumptions — and clean slates that tend to function like mirrors — are usually central to our experience of Preminger’s work. His narrative lines are strewn with deceptive counter-paths, shifting viewpoints, and ambiguous characters who perpetually slip out of static categories and moral definitions, so that one can be backed out of a conventionally placid Hollywood mansion driveway by somebody and something called Angel Face (1952) (and embodied by Jean Simmons) only to be hurtled without warning over the edge of a cliff. As for tabulae rasae, there is Angel Face herself and her numerous weird sisters — among them Maggie McNamara in The Moon Is Blue (1953), Jean Seberg in Saint Joan (1957) and Bonjour Tristesse (1958), Eva Marie Saint in Exodus (1960) and, closer to the cradle, the almost invisible Bunny Lake in Bunny Lake Is Missing (1965) and Alexandra Hay in Skidoo (1968). There is even Jean Seberg, whose part in A bout de souffle, Godard informs us, “as a continuation of her role in Bonjour Tristesse. I could have taken the last shot of Preminger’s film and started after dissolving to a title, `Three Years Later’. Or, to return to our starting point, there is Gene Tierney in Whirlpool (1949) and Laura.

Laura even begins with a false impression. After the credits the screen grows dark, and the voice of Waldo Lydecker (Clifton Webb) tells us, ‘I shall never forget the weekend Laura died.’ We go on to discover that a body whose face has been destroyed by a shotgun blast is discovered outside Laura’s flat. Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews), a detective, sets out to learn who she was; haunted by her portrait and one of her favorite records, smelling her perfume and fingering her clothes, he fills the tabula rasa of her absence with a dream (we are implicitly invited to do the same), and then falls in love with the dream. At which point the real Laura, not dead at all, walks into the room.

At least four Lauras are created during the course of the film: one by Lydecker (he refers to her as his “creation”); one by McPherson; a third by the audience, who follow Lydecker’s narration and McPherson’s investigation, and then a fourth by Gene Tierney as the lady herself, who enters the film to reconcile and confound all the other versions. But dreams have been generated by this time, and for the remainder of the film we see them being tested by and contrasted with their original stimulus, with gliding camera movements serving to reassemble and rearrange all the characters in relation to this central axis, a series of permutations which place everyone ‘on trial’, in a kind of moral limbo. Even our own qualifications as impartial witnesses are thrown into doubt by the shifting perspectives. Like the characters, we are prone to look at faces and invest portions of ourselves in them, to the extent that each important character becomes a different kind of mirror.

To some extent, all Preminger’s films are enquiries, and if that is what makes them interesting, it is also what makes them problematic. (Some questions are more interesting than others.) A filmmaker like Rossellini, Rouch or Preminger who chooses to pose questions rather than answer them is likely to encounter misunderstandings, particularly when these questions are placed within a fictional mode (e.g., Rossellini’s Viaggio in Italia, Rouch’s Gare du Nord, Preminger’s Whirlpool), and even more so when, in Preminger’s case, the plots pretend to resolve the questions which the style raises. Thus in The Thirteenth Letter (1951), for example, a remake of Clouzot’s Le corbeau, the search for the author of poison-pen letters in a small Canadian community so relentlessly places every character under suspicion that the denouément proves to be anticlimactic, and wholly inadequate for releasing the anxiety which has been established.

As the least apparently autobiographical of all ‘personal’ Hollywood stylists, Preminger frequently mystifies the spectator who is looking for a fixed moral reference. When his camera starts to move, one feels that his characters are being not so much shown as observed, juxtaposed, interrogated; when it remains stationary, we might more readily confuse a specific statement or stance with Preminger’s viewpoint, but then a subsequent shot or scene will usually come along to undermine that impression. The son of a public prosecutor and Attorney General of the Austrian Empire, Preminger grew up in Vienna watching trials — and later became a lawyer himself, after acting in several Max Reinhardt productions and directing a few plays –so it is hardly surprising that he should see most dramatic situations in the form of legal proceedings, where truths tend to be clearly relative rather than absolute.

The melodramas he directed between 1944 and 1952, which comprise the bulk of his most durable work, are largely a series of arabesques woven around obsessions and dangerous seductions. All of them were made for Fox (except Angel Face, which was made for RKO), and many of the same actors — Dana Andrews, Gene Tierney, Charles Bickford, Linda Darnell — reappear, like permutations in a recurring dream. Against their own better judgments and intentions, McPherson, in Laura, falls in love with a supposedly dead woman; Eric Stanton (Andrews), in Fallen Angel (1945), plans to marry June Mills (Alice Faye) for her money and then falls in love with her, while the waitress who inspired his scheme (Darnell) is murdered by an obsessive police inspector (Bickford); Ann Sutton (Tierney), in Whirlpool, falls under the literally hypnotic influence of Dr Korvo (José Ferrer), and thereby becomes a murder suspect; a tough cop (Andrews) in Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950) accidentally kills a murder suspect, and then falls in love with his widow (Tierney); and Frank Jessup (Robert Mitchum) continues to trust the murderous Angel Face long enough to be destroyed by her.

The technical competence of these films varies considerably (the acting in Laura, for instance, is much more polished than that in Whirlpool); but Preminger’s capacity for exploiting and exploring all their latent ambiguities remains fairly constant. During the same period he also directed two Lubitsch projects (A Royal Scandal, 1945; That Lady in Ermine, 1948) and a Lubitsch remake (The Fan, 1949); he also made Centennial Summer (1946), an amiable spinoff of Minnelli’s Meet Me in St Louis and arguably Preminger’s best musical; Forever Amber (1947), the first of his cautiously ‘audacious’ best-seller adaptations; and Daisy Kenyon (1947), a stately soap opera with some of the ambience of a film noir). And except for perhaps the first two or three, his interrogatory manner persists in all of these works. But the apogee of this period remains Angel Face, the last film Preminger directed before he became an independent producer, and certainly the most enigmatic and haunting of all the works after Laura. Jacques Rivette described Preminger’s mise en scène on this occasion as “the creation of a complex summary of characters and sets, a web of connections, an architecture of relations,” and remarked that “the relationships of characters create a closed circle of exchanges, where nothing solicits the spectator”.

The fascination and dangers of this approach — more than apparent in Rivette’s own first feature, Paris nous appartient — are roughly equivalent: if every character and viewpoint represented is open to question, the spectator is virtually required to project his own fancies and biases into the narrative in order to make it coherent. And this becomes problematic as soon as Preminger begins to calculate these mirror-like ‘open spaces’ according to intricate commercial assessments of his audience, and uses his approach to explore Big Subjects and promote parlor debates in which the intrigues serve an increasingly pedagogic — and occasionally even propagandistic — function.

Without denying the stylistic, psychological and narrative interest of such films as The Court Martial of Billy Mitchell (1955), Exodus, Advise and Consent (1962), The Cardinal (1963), In Harm’s Way (1965) and Hurrv Sundown (1967), it must be acknowledged that on a thematic level — the level on which they are ostensibly presented — they rarely proceed beyond the intellectual level of Reader’s Digest. And if most of the films in this period arc accomplished in their overall designs and surface details — particularly their use of period décor and locations — their seriousness is usually compromised by the commercial safeguards round which they are structured. Admittedly, Preminger achieved notoriety when two of these films were condemned by the Legion of Decency; but now that the shock value of the words “virgin” and “pregnant” and the subject of heroin addiction has appreciably receded, The Moon Is Blue emerges as a flat, toneless and innocuous attempt at comedy, while the remaining interest of The Man With the Golden Arm (1955), a sleazy studio job, resides more in the imaginative use of music (e.g., a Shelly Manne drum solo to punctuate a ‘cold turkey’ withdrawal) and the relative funkiness of Frank Sinatra and Kim Novak than in the all too superficial exploration of its subject.

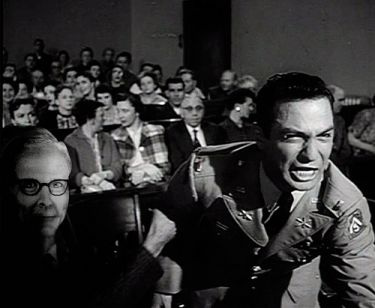

Advise and Consent has been praised as a bold exposition of the inner workings of the American government, a masterpiece of “ambiguity and objectivity,” and even as a revelation of Preminger “as one of the cinema’s great moralists”. But notwithstanding its strengths as entertainment (a cleanly articulated narrative following a large cast through a complicated plot; a fine neo-Wellesian performance by Franchot Tone as the President, and a showier one by Charles Laughton that deftly mixes ham with a more subtle rye; a lot of sensually grandiloquent tracks and cranes around Washington locations), the question remains how serious it actually is about its subject. When the Saul Bass credits conclude with the dome of the Capitol lifting to reveal Preminger’s name, the limitations of the whole enterprise are already apparent.

The film is concerned not so much with politics or government as with public relations. According to its dramaturgy, the central issues involved in the appointment of Robert Leffingwell (Henry Fonda) as Secretary of State are his inconsequential fellow-traveler past and a homosexual episode in the past of the senator (Don Murray) investigating him. Neither of these facts is shown to have any political importance apart from these men’s public reputations; but fundamentally the film is concerned with nothing else — it appears, in fact, that much labor was expended so that the audience wouldn’t have to worry about the political issues at all. In the climactic speech — which, far from being “objective,” is clearly designed to impress us with its moral justice — Senator Munson (Walter Pidgeon) condemns the blackmailing Senator Van Ackerman (George Grizzard) by asserting, “We tolerate just about anything here — fanaticism, prejudice, demagoguery — [ … ] but you’ve dishonored us.”’ And this indeed is the stance of the entire film, which tolerates and even accommodates prejudice and demagoguery as long as it remains sufficiently theatrical (such as Laughton’s juicy performance) but comes out squarely against blackmailing, nervous excitability, and bad manners (Grizzard is cast as a pure villain from the moment he appears).

To complicate matters, Van Ackerman is shown as a pacifist while Laughton portrays a jingoist; as Penelope Houston has noted, “The film is as well provided with checks and balances as the constitution.” But the net effect of all these counter-weights is to convey only the appearance of objectivity, which contrives to make Preminger’s hidden biases more subliminally persuasive. Equivalent strategies are to be found in projecting the Zionism of Exodus and the anti-Catholicism of The Cardinal: he will welcome antagonistic points of view within a single shot so that he can watch them co-exist, mingle, synthesize, or compete for supremacy, but he always makes sure that the overall ‘composition’ of these elements conveys a given slant, and the ostensible appeal to the spectator to ‘Use his own intelligence’ is often a very clever means of directing and programming that intelligence. As Jean-André Fiéschi has remarked of Tati’s Playtime — a film, like many of Preminger’s, largely concerned with crowds and multiple vantage points —- “we are presented with wide avenues, all the better to guide us on to carefully illuminated footpaths.” The journey taken is implacably one from A to B, but we are given a choice of diverse routes by which we may traverse the distance.

Some of the films in Preminger’s middle period escape some of the above strictures. River of No Return (1954), made to fulfil his Fox contract, benefits from an interesting performance by Marilyn Monroe and a pioneering use of CinemaScope which grants the viewer an unusual amount of liberty in spotting relevant actions and details; and the fact that it doesn’t profess to take up a Significant Theme leaves Preminger relatively free to explore the characters for their own sake, as he did in the early melodramas. Bonjour Tristesse, despite its celebrated source and more opulent production values, is aided by a similar concentration of focus, as well as a striking juxtaposition of black and white with color to reflect the tensions between a somber present in a Parisian nightclub and a reckless past on the Riviera. Somewhat prophetically, Rivette noted at the time that the passage from Angel Face to this 1958 film traced a development from the sketch to the fresco, and in more ways than one Bonjour Tristesse represents — and its black-and-white/color contrasts echo — a marriage between the funereal moods and modulations of Angel Face and some of the brassier showmanship of a one-ring circus like Carmen Jones (1954).

Anatomy of a Murder (1959), easily the most graceful and sustaining of the Preminger bestseller monoliths, is the only obvious instance in his work where the ambiguities unraveled in the style are supported by a deliberately unresolved ambiguity in the plot. Harking back to the thriller format of his better Fox films without the usual undertow of neurotic anxiety, and dealing with the law (his pet subject) more centrally here than elsewhere in his work, he carries us through a murder trial without ever revealing whether the defendant is guilty or innocent, thereby encouraging the audience to become a separate jury, and focusing much of its attention on the legal procedures themselves. In the process, he establishes an evocative and credible portrait of a small town in Michigan, provokes a number of assured performances (from James Stewart, Lee Remick, Ben Gazzara, Arthur O’Connell, Kathryn Grant, George C. Scott and Joseph N. Welch) and, above all, imposes a lightness of touch that is apparent nowhere else in his work. (Oddly enough, despite its serious elements, Anatomy of a Murder comes much closer to working as a successful comedy than more heavyhanded efforts like The Moon Is Blue and Skidoo.) Perhaps because of its uncharacteristically loose and relaxed ambience — helped in no small measure by Sam Leavitt’s photography and Duke Ellington’s score — it endures as the least pretentious and most convincing of all Preminger’s ambitious works.

The relationship of the French word procès to the English word process highlights a preoccupation common to most of Preminger’s films, which not only places characters ‘on trial’ but carefully charts the changes they go through in relation to various corporate and social entities. A standard criterion of implicit or explicit judgment for Preminger is social adaptability, and the typical villain or victim is usually identified by an obsessive personality that is unable to adapt and festers in isolation, frequently behind a deceptive mask: Dana Andrews and Clifton Webb in Laura, Linda Darnell in Centennial Summer, José Ferrer and Gene Tierney in Whirlpool, Charles Boyer in The Thirteenth Letter, Jean Simmons in Angel Face, Eleanor Parker in The Man with the Golden Arm, Jean Seberg in Bonjour Tristesse, Ben Gazzara in Anatomy of a Murder, Sal Minco in Exodus, George Grizzard and Don Murray in Advise and Consent, Kirk Douglas in In Harm’s Way and Keir Dullea in Bunny Lake Is Missing all embody different versions and varying extremes of this malady, and it is scarcely accidental that virtually all the major acts of violence in these films — excepting only the massive battles in Exodus and In Harm’s Way — can be traced back in some way to these characters’ isolation or maladjustments.

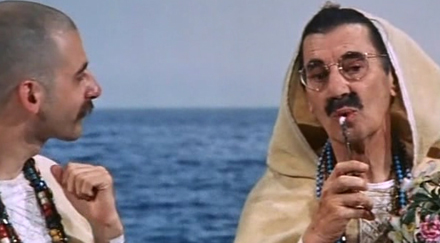

One of the many peculiar aspects of Preminger’s recent films — Skidoo; Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon (1970); Such Good Friends (1972) — is that with few exceptions, all the central characters are viewed as alienated outsiders; it is no small irony that Carol Charming, in an extraordinarily grotesque performance, comes closer to being a balanced and flexible character than anyone else in Skidoo.

Much of the unpopularity (as well as the potential fascination) of these three films derives from the way that the theme of isolation vs. social cohesion becomes so shrill and ostentatious that all the latent perversities — what one might call the ‘disturbing undertones’ — implicit in the earlier works come screaming to the surface in a torrent of vulgarity, as if some restraining force which previously submerged, sublimated or localized these aberrations has finally broken loose to flood the screen. This is undoubtedly an over-simplification: storm warnings are already evident in the garish excesses of works at least as early as That Lady in Ermine and Carmen Jones; and the increasingly broad flourishes of In Harm’s Way, Bunny Lake Is Missing and Hurry Sundown certainly begin to suggest a passage from fresco to comic strip. When Preminger wants to indicate the prissiness of Jere Torrey (Brandon De Wilde) in In Harm’s Way, the gesture is so wide and sweeping that one could drive a truck through it; the delirious finale of Bunny Lake Is Missing (1) registers like an effort to overreach all the rococo effects the film has already accumulated; while Hurry Sundown veers from Jane Fonda performing fellatio on an alto saxophone to liberal fantasies about blacks which contrive to cover the distance between Stepin Fetchit and Martin Luther King.

In Skidoo, alongside Preminger’s efforts to bridge the generation gap by cramming stand-ins for Middle America (Jackie Gleason, Carol Charming, Mickey Rooney, etc.) and counter-culture (Alexandra Hay, John Philip Law) into the same shots, and putting Gleason through an acid trip, one finds an attempt to blend all sorts of irreconcilable Hollywood genres, or what Richard McGuinness has called “comic books calcifications of them”. Both these attempts achieve a tacky (if appropriate) apotheosis in a Garbage Can Ballet rendered as an LSD vision of two prison guards, when Gleason and his hippy cellmate construct an escape balloon out of plastic food containers. Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon saddles its three leads (Liza Minnelli, Ken Howard, Robert Moore) not only with crippling afflictions but with one sexual trauma apiece, each delineated in a lurid flashback; and Such Good Friends chronicles a wife’s discovery of her husband’s multiple infidelities — while he is dying because of medical incompetence — with such unrelenting excruciation that the failed comedy of Skidoo and the failed tragedy of Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon seem to blend, like a multiplication of two minus numbers, into a very pungent and persuasive (if ungainly) compound of black comedy and bright tragedy.

The muted expressionist undertones of the Fox melodramas become blatant overtones in this late demonic trilogy, and such sequences as the acid trip in Skidoo, the flashbacks in Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon and the stream of consciousness fantasies of Such Good Friends are unprecedented in his career, suggesting an arsenal of modish tactics that consistently miss the mark: aimed at a commercial target, each technique and topical subject backfires, drawing attention more to Preminger’s obsessions than to those of his characters. (Particularly striking is the strident flashback accorded to Liza Minnelli in Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon, a suite of variations on the two sides of both her sexual nature and her acid-scarred face — reflected in the alternate use of Bach and dance music on the soundtrack and the angle/reverse- angle cutting — which comes across like an experimental student film made out of discarded Hollywood materials.) If the spirit of late Fritz Lang hovers over the grim ambiguities of the Fox melodramas, the ruling manner of the last films suggests the style and some of the preoccupations of yet another Viennese-born director, Stroheim; but it is an uncontrolled Stroheim run amok in the dishevelments and second thoughts of another age, a Stroheim with most of the ironies and fetishes intact but none of the restraint, and — camera movements apart — little of the grace or visual taste. And the enquiries that served to enrich the substance of the melodramas and disguise the superficialities of the big theme streamliners operate here as a cruel exposure, revealing the limitations of the material at every turn.

Perhaps it is as perverse as Preminger himself to prefer these late camp works to the Sunday supplements of his middle period. Yet for all their hysterical indigestibility, they are candidly (and sometimes painfully) personal works: what is lost in craftsmanship is gained in lucidity, even if this lucidity is often the expression of an ambivalence that borders on the schizophrenic. The last scene of Such Good Friends, when the heroine (Dyan Cannon) disappears with her two sons into Central Park, can be seen as the character’s triumphant survival of her ordeal if we listen to the soundtrack song, or as her ignoble defeat if we look closely at her face. Thus the ambiguity beginning in Laura ends in pure and simple contradiction: the blind viewer may say ‘comedy’, the deaf viewer may say ‘tragedy’, but the spectator condemned to see and hear will have to settle, like Preminger, for something else.

–from Cinema: A Critical Dictionary (1980)

Footnotes

1. Belated afterthought: almost 30 years after writing this essay, an opportunity to see the film again suggested that the stylistic overkill of the final sequence —- arguably occasioned by an unsufficiently motivated (or inadequately explained) denouément — may indeed mark the decisive turning point towards Preminger’s garish late manner; the next feature after that was Hurry Sundown. [2002]