From American Film (November 1981). — J.R.

Old Wave Saved from Drowning

By Sandy Flitterman and Jonathan Rosenbaum

Think of French cinema, and the New Wave springs immediately to mind. This association is hardly accidental. History, it is often said, gets written by the victors. And the victories recounted in the standard film histories — whether they are critical successes or box-office triumphs — are inevitably at the expense of other movies, individuals, or social trends that presumably failed to scale the same heights.

But the New Wave, like other movements in film history, is significant not only for what it gave us — films like Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, Godard’s Breathless, and Resnais’ Hiroshima, mon amour — but also for what it took away, for the films it rebelled against, repudiated, buried in the dustbin of history. Now a fascinating new program of forty-six subtitled French films made between 1930 and 1960 helps sketch out the rudiments of just such an alternative history.

This group of films, appropriately entitled “Rediscovering French Film,” has been put together by New York’s Museum of Modern Art in cooperation with the French government and, after premiering in Manhattan this month, is scheduled to travel next year to Washington, Berkeley, Los Angeles, Houston, and Chicago. Selected by Adrienne Mancia and Stephen Harvey, of the museum, with the help of Richard Roud, director of the New York Film Festival, this package promises rich and various discoveries, and will undoubtedly lead us to revise some of our notions about the New Wave itself, as well as the cinema that preceded it.

For one thing, the youthful antiauthoritarian eclecticism and bohemianism projected by fledgling directors like Godard, Chabrol, and Truffaut led many American filmgoers to assume that the New Wave was thumbing its nose at stodgy postwar Gaullism. Today, in view of the astute political implications of the work of a Jean Renoir or a Jean Grémillon, it is possible to conclude that something closer to the reverse was true. (Godard himself now even refers to Breathless as a Fascist film.) At the very least, some of the films in this new series can help us to understand the difference between rebellious exuberance and class analysis.

It was precisely this kind of political ambiguity which was fostered by the appearance of Truffaut’s polemical l954 article “A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema,” in which he identified two warring camps-the “tradition of quality” and an “auteur’s cinema.” Indeed, what’s often overlooked about this article is that the objections it lodges against the so-called psychological realism and prestigious literary adaptations of such directors as Claude Autant-Lara, Yves, Allégret, René Clément, and Jean Delannoy are basically conservative ones. For Truffaut, sins of these filmmakers –- especially the scriptwriting team of Jean Aurenche and Pierre Bost, who worked on such famous films as La Symphonie Pastorale (1946), Devil in the Flesh (1947), and Forbidden Games (1952), included their antimilitary and anticlerical attitudes as well as their aesthetic assumptions about adapting literary classics. This “tradition of quality” was perceived by Truffaut as blasphemous and profane in relation to the spirituality which he perceived in such individual, creative auteurs as Robert Bresson, Abel Gance, Max Ophüls, and Jean Renoir.

Partially as a consequence of the New Wave’s success, certain French films that preceded it in American art houses –- such as Devil in the Flesh and Forbidden Games — gradually went into decline. In 1929 — when eighty-five percent of the films shown throughout the world were made in the United States — according to film historian Léon Moussinac, French production dropped to only fifty features a year. In response to this dire situation, and perhaps out of a need to develop a national cinematic identity, certain French directors, scriptwriters, actors, and technicians forged lasting alliances which produced an exciting renaissance in French cinema. The movement combined poetic realism with the political sentiments of the Popular Front, injected populist sentiments and fresh subjects from daily life into the meat-and-potatoes staples of Saturday night cinema, and utilized the attraction of established actors for low-budget star vehicles.

Directors Jean Renoir and Marcel Carné,scriptwriters Jacques Prévert and Charles Spaak, actors Jean Gabin and Arletty, and art directors Lazare Meerson and Léon Barsacq were all representative figures in this upheaval. It’s important to note the difference between this collective process and the systematization of Hollywood production of the same time. What marked French cinema during this period was the truly collaborative nature of the projects, as opposed to a strict division of labor.

Running parallel to this industry trend were the impulses that led, in 1936, to La vie est à nous — an anti-Fascist propaganda film supervised by Renoir for the French Communist party, and made in collaboration with Jacques Becker, Jean-Paul Le Chanois, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Jacques B. Brunius, Gaston Modot, and many others, intended to be shown outside of commercial circuits, at public meetings. By that year, authoritarian governments were ruling Austria, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Portugal, and Yugoslavia. The film was made collectively in the hope of influencing the May elections in France, and it was financed by the contributions of individual party members.

Renoir’s previous commercial feature, Le Crime de M. Lange, had already celebrated the growth of a worker’s cooperative. The more didactic nature of La vie est à nous makes it in some respects a film even further ahead of its time –utilizing bold displacements and transitions between documentary and fictional material, with techniques anticipating Citizen Kane, New Wave films, and Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Our Hitler: A Film From Germany.

***

On the basis of the dozen or so films in the upcoming French film program that we’ve been able to preview, it’s clear that one major source of interest in these movies is what they reveal about the temper and mood of France, socially and politically, at the time they were made. Most of them, to be sure, do this much less directly than La vie est à nous.

One intriguing “B” film called Les Disparus de Saint-Agil (1938) is a melodrama set in a boys’ school which co-stars two of the greatest heavy muggers of all time, Michel Simon and Erich von Stroheim, as rival teachers. Introducing itself in an opening title as an escapist tale about childhood adventures, the movie begins appropriately with the nocturnal meeting of a boys’ secret society, “Chiche-Capon.”

Before long, two of Chiche-Capon’s members mysteriously vanish from the school. The story eventually includes a subplot about counterfeiting, as well as frequent references in the dialogue to the imminent outbreak of war, which was indeed threatening France at the time. A paranoid fear of foreigners held by one of the teachers (Simon) leads to the persecution of another (Stroheim), contributing an expressionist overlay to the tensions of an otherwise routine thriller plot, routinely directed by Christian-Jaque.

Abel Gance’s Paradis perdu (1939), an even stranger kettle of fish, reflects war jitters more directly, by making the outbreak of World War I the key traumatic event in its ultraromantic plot. Pierre Leblanc (Fernand Gravey), an artist, meets Janine Mercier (Micheline Presle), a dressmaker, during a fireworks celebration on Bastille Day. After he enjoys a dreamlike, meteoric rise to fame as a dress designer, they marry, but war is declared during their honeymoon in the country (“Fishing’s over,” exclaims a peasant, “shooting’s started!”), and he goes off to the front. Janine dies in childbirth while he’s away, and in the remainder of the film we watch Pierre overcome his bitterness about his lost paradise, as his daughter, Jeanette (also played by Presle), finds her own romantic happiness.

Max Ophüls’ neglected De Mayerling à Sarajevo (1940) makes the link between the two world wars even more explicit. Its plot is a quasi-fictional prelude to the specific incident that precipitated the outbreak of World War I, the assassination of Austrian archduke Francis Ferdinand by a Serbian nationalist in l9l4. The film actually concludes with newsreel footage and a narrator stating (over a rousing version of *La Marseillaise”), “The sons of the men of l9l4 are now finishing the job of defending freedom and liberty that was started by their fathers.”

Prior to this uncharacteristic ending, the director shows his usual flair for examining the relationships within a social complex, in a style of long takes, which Ophüls shares with Renoir and Jacques Tati, that preserves the integrity of space. The opening scene depicts the frantic preparations for the birthday party of Emperor Franz Joseph in a series of fluid, choreographed camera movements. And throughout the film, royal symbols (such as the empire’s official seal, the Hapsburg crown, and an imposing military statue) provide much of the opulent visual subtext, contributing to the exquisite sense of detail characteristic of the man who directed Letter From an Unknown Woman and Lola Montès.

The plot concerns Francis Ferdinand (John Lodge), the emperor’s democratic-minded great nephew, who falls in love with Sophie Chotek (Edwige Feuillère), a Czech countess beneath his station, who shares his political views. Both his mother and great uncle try in different ways to subvert the romance, the former suggesting an amorous “arrangement,” the latter employing espionage and military strategies. But the crown-versus-heart theme is ultimately replaced by a more explicitly political concern. Forced to give up certain royal privileges in order to marry Sophie, Francis Ferdinand continues to work for a united Austria until he dies from an assassin’s bullet.

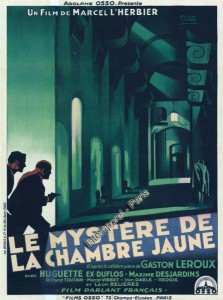

Marcel L’Herbier — whose spectacular (and spectacularly expensive) silent masterpiece L’Argent (1927), an updating of Zola’s Money, has only recently been rediscovered by critics — is a director still in the process of being reevaluated, and his four films in the series will undoubtedly speed up that process. All have rather fragrant titles, the first two of which are adaptations of works by pop writer Gaston Leroux: Le Mystère de la chambre iaune (1930), Le Parfum de la dame en noir (1931), Le Bonheur (1935, featuring Charles Boyer and Michel Simon), and La Nuit fantastique (1942).

La Nuit is a charming fantasy made during the Occupation that has the same two leads as Gance’s Paradis perdu, Fernand Gravey and Micheline Presle. It conveys some of the cozy chiaroscuro and film noir ambience one might associate with certain Hollywood films released the same year (Casablanca, I Married a Witch, The Magnificent Ambersons, Cat People), as well as with Truffaut’s recent movie about a theater group during the Occupation, The Last Metro.

***

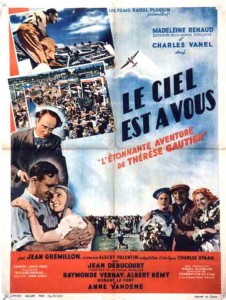

With the four films in the French show by Jean Grémillon — Gueule d’amour (1937), Lumière d’été(1943), Le ciel est à vous (1944), and Pattes blanches (1948) — one is faced with a seminal director whose work is virtually unknown in this country. According to critic and historian Bernard Eisenschitz, Grémillon directed a variety of films “not much resembling each other, thanks to production problems as well as to a desire to repeat nothing and to refuse nothing, whether routine melodrama or an entry in the Encyclopédie filmée.” From an auteurist’s point of view, the diversity of Grémillon’s output might be seen as a professional liability, and it prevents us from neatly identifying him as a single creative force. On the other hand, Grémillon’s inventiveness and stylistic range mark him as one of the most exciting directors of the period.

Just on the strength of Lumière d’été, one of the incontestable masterpieces of French cinema during the Occupation, Grémillon must be regarded as an essential figure. The movie is remarkable on many counts. A complex portrayal of Vichy decadence, as represented by the wealthy country baron Patrice Le Verdier (Paul Bernard), a libertine whom Georges Sadoul linked to the heroes of the Marquis de Sade, it delineates a rather bold political subtext, particularly when a large group of mine workers spontaneously overcomes this rake on the edge of a cliff.

As an intricately composed mise en scène of social interactions enhanced by some striking sound innovations (including an impressionistic aural flashback in which an entire sequence of events is cunningly constructed out of evocative sounds and musical fragments), Lumière d’été suggests the work of Jacques Becker and Jean Renoir. (In fact, Becker’s last and best film, Le Trou [1960], a painstaking prison-escape account whose full, 126-minute version has never before been seen in this country, will conclude the series; Becker’s earlier Goupi mains-rouges [1943] and Les rendezvous de juillet [1949] will also be seen.)

Lumière d’été, a Racinean drama about a tragic relay of frustrated affections (wherein A loves B, who loves C, who loves D), was written by the poet Jacques Prévert, whose film credits also include Le Crime de M. Lange and Les enfants du paradis (Children of Paradise, 1945). All of the above elements (sociopolitical allegory, visual and aural patterning, trenchant dialogue) converge with the talented cast — Bernard, Madeleine Renaud, Pierre Brasseur, Madeleine Robinson, and character actor Marcel Levesque — at a climactic masked ball, a complex visual orchestration in which Grémillon’s dazzling mise en scène and Prévert’s literary allusions (to Manon Lescaut, Hamlet, and William Tell, as well as de Sade) are allowed to have a field day. Based on a 1937 incident, Grémillon’s Le Ciel est à vous, with dialogue by Charles Spaak, is a stirring populist drama about a working-class husband and wife (Madeleine Renaud and Charles Vanel) whose mutual aspirations drive them to sacrifice their daughter’s musical talent and risk the wife’s life to win a women’s aviation competition. Once again, music and sound play an unusually forceful dramatic role. At one point, a crowd’s feverish offscreen chanting of the hero’s name seems like an ominous threat rather than a warm invitation, recalling the vengeful miners in Lumière d’été.

***

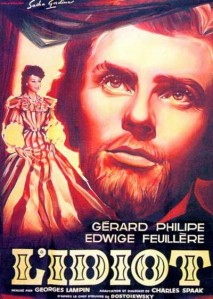

The MoMA series features several adaptations of classic eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European novels: Raymond Bernard’s Les miserables (1934), Robert Bresson’s Les dames du bois de Boulogne (1945, derived from an episode in Diderot’s Jacques the Fatalist), Georges Lampin’s The ldiot (1946), Christian-Jaque’s lengthy The Charterhouse of Parma (1948) — the latter two were vehicles for actor Gérard Philipe -– and Alexandre Astruc’s Une vie (1958), the only color film in the entire series.

In the case of the Bresson masterpiece, one finds a rare instance of relatively pure directorial authorship contradicting the collective and collaborative tendencies of the period. One should note, however, that Diderot’s dialogue in this film was adapted to a contemporary setting by Jean Cocteau, whose filming of his own plays Les parents terribles and L’aigle à deux têtes — both 1948 — provide further exceptions. The second and last of Bresson’s films to use professional actors, (notably Maria Casarès and Paul Bernard), Les dames du bois de Boulogne is also perhaps the first that clarifies his distance from psychological motivation and naturalistic detail.

While the interest of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot revolves mainly around Charles Spaak’s crisp dialogue, Léon Barsacq’s sumptuous sets (including a lovely miniature of St. Petersburg at night, which the camera twice traverses in a leisurely pan), and Gérard Philipe’s charming and nuanced performance as the twenty-seven-year-old Prince Myshkin (opposite Edwige Feuillère’s Nastasia), The Charterhouse of Parma tends to reduce Stendhal to little more than his intrigues. The latter film is particularly interesting, however, as a somewhat calcified Classics Illustrated form of literary piety — an attempt at a European Gone With the Wind which solidly embodies that “tradition of quality” which Truffaut and his New Wave colleagues wished to destroy.

There’s a scene in The Charterhouse of Parma during which the character Gina (Maria Casarès) sits at a mirror, applying face cream, while telling Count Mosca about the ravages of age on a woman’s beauty. It offers an interesting cross-reference to the sequence in Truffaut’s Jules and Jim (1962) in which Catherine (Jeanne Moreau) is also seen seated by a mirror, applying face cream. In the Christian-Jaque/”tradition of quality” version, Casarès’ makeup is unrealistically still intact by the end of the scene, the cream carefully applied in accordance with the photographic requirements of the star portrait. In the Truffaut/New Wave scene, on the contrary, Moreau’s face is left totally denuded at the end, giving it a deglamorized appearance — an effect which exemplifies the much-celebrated irreverent spontaneity of the New Wave.

The Charterhouse of Parma certainly confirms many of the New Wave’s accusations against the “tradition of quality,” but any true reevaluation of the missing links in French film history will undoubtedly have to plow back still further — through the limitations of this or any single selection. It will have to look into the broader question of what keeps certain films and filmmakers visible or invisible in our history books, which are always tentative and provisional places, regardless of what they may say.

Although a part of “Rediscovering French Film” seems to represent the very strain of that gilt-edged “quality” cinema of a literary bent that Truffaut opposed — including movies directed by Yves Allégret, René Clément, and Jean Delannoy — still another portion of the selection can be said to flesh out that cinéma d’auteur of Becker, Bresson, Cocteau, Gance, and Ophüls that he championed. Perhaps even more important, the range of work on display is sufficiently wide to pass beyond both of Truffaut’s neat categories of 1954 and to raise the suspicion that in order to arrive at a truly comprehensive picture of French film history, we may have to invent some new critical categories and reconnaissance strategies of our own.