From the Chicago Reader (April 12, 2002). — J.R.

Human Nature

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Michel Gondry

Written by Charlie Kaufman

With Patricia Arquette, Tim Robbins, Rhys Ifans, Miranda Otto, Robert Forster, Mary Kay Place, Rosie Perez, and Miguel Sandoval.

The energizing comic wackiness of Being John Malkovich made me wonder what to expect next from screenwriter Charlie Kaufman and director Spike Jonze. But their latest collaboration, Human Nature — which Kaufman wrote, Michel Gondry (a music video director, like Jonze) directed, and Jonze produced, along with three other people, including Kaufman — is disappointing. It’s almost as wacky in spots as Being John Malkovich, and at first I found it funny and provocative. But by the end of the ride I felt I’d been taken for one. Then I remembered that Being John Malkovich had also left me with a somewhat sour feeling; ultimately Kaufman had overplayed his hand.

The diminishing returns may have something to do with the filmmakers’ postmodernist approach — the flip attitude that puts somewhat mocking quotation marks around everything, so that a more apt title of this movie might be “Human” “Nature.” This makes me wonder if the TV backgrounds of Kaufman, Gondry, and Jonze have something to do with their built-in skepticism.

The film has three central characters who take turns narrating portions of their collective story in flashbacks: After being arrested for murder, Lila (Patricia Arquette) begins by saying, “I’m not sorry.” Puff (Rhys Ifans) testifies before a congressional committee, saying, “I’m sorry.” And Nathan (Tim Robbins), the murder victim, sits in an all-white antechamber of some sort with a bullet in his head, declaring, “I don’t even know what ‘sorry’ means anymore.” Then, like characters in a Kurt Vonnegut novel, they proceed to explain what they mean.

As a girl, Lila discovers she’s growing inordinate amounts of body hair, which turns her into a miserable recluse, then a performer in a circus freak show — until she discovers a love of nature, goes to live like an ape in the forest, and becomes a successful nature writer. As a boy, Puff is abducted by his lunatic father and raised like an ape in the forest. As a child, Nathan is so browbeaten by his parents (Robert Forster and Mary Kay Place) into learning correct table manners that he becomes a scientist who devotes his life to teaching table etiquette to lab mice.

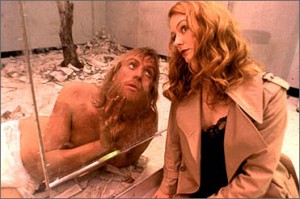

So far, so good — or is it? At 30, Lila is so sexually frustrated she returns to civilization and submits to electrolysis done by her friend Louise (Rosie Perez), who matches her up with Nathan, now a 35-year-old virgin; Louise knows about him because her psychiatrist husband (Miguel Sandoval) has him as a client (lack of discretion on the part of a therapist appears to be taken for granted). Lila and Nathan — who knows nothing of her past and condition — immediately hit it off, and when they discover Puff in the woods, they take him back to Nathan’s lab and place him in a glass cage. Using an electric collar as discipline, they then teach him “civilization” — which to them means curbing his sexual appetites, using the proper fork, and cultivating an appreciation for opera and poetry. Unfortunately, in the meantime Nathan has developed a crush on his French lab assistant Gabrielle (Miranda Otto) and winds up leaving Lila for her when he discovers Lila is still growing body hair (which she’s been shaving in secret).

By the end of the story, Lila and Puff are a couple and have returned to the woods, and all three main characters have become so confused and divided about their “civilized” and “animal” natures that they can behave only incoherently. Lila continues to give Puff electric shocks when he’s too brazen about his sexual desires, and Nathan makes apelike noises when he shows up in an effort to win Lila back. The sexual frustrations of all these characters turn out to be what most defines them — calling to mind the comic refrain of the main characters in Being John Malkovich.

At first these reflections on our animal natures and what we regard as civilized behavior might seem profound in some way. That was my impression as I laughed at some of Kaufman’s loonier spins on his material; I thought I might be watching some oddball fusion of A Clockwork Orange and Tarzan’s New York Adventure.

But then the postmodernist quotation marks started becoming too glaring to overlook. I realized that what seemed like sophisticated skepticism on the part of the filmmakers about some philosophical positions necessitated abject adherence to others. Females with excess body hair are deemed “uncivilized” by American middle-class culture, but not by certain Latin working-class cultures. Attending the opera might seem “civilized” to the American middle class, but an Italian taxi driver might not see it as all that different from attending a sports event. Similarly, many Americans associate things such as Brie, cappuccino, and croissants with civilized behavior, though Europeans don’t. In the last two cases, the Americans are confusing what in this country are tokens of upscale living with universal emblems of civilization.

What we see of “nature” in Human Nature consists exclusively of parodies of Hollywood stereotypes, such as Tarzan swinging on vines and Lila singing to the forest animals like a Disney heroine. What we perceive as Gabrielle’s Frenchness is no less cartoonlike. By calling itself Human Nature, this movie is implicitly asking us to take these stereotypes as universal archetypes — a kind of TV shorthand for what we should immediately recognize as “French,” “civilization,” “science,” “nature,” and even “human.” This is one reason Lila, Puff, Nathan, and Gabrielle don’t register as characters with any substance, human or otherwise, and it’s why we can’t really care about them or find much meaning in what happens to them.

The way these characters are initially used to tweak us about some of our own conditioning as TV watchers — which teaches us to accept instantly recognizable icons as substitutes for complex realities — isn’t sustained. How hairy Lila is when she returns to the forest with Puff is deliberately obscured because of the camera’s placement. And the promisingly daft idea that Nathan’s parents would adopt another boy after Nathan grows up and then prefer the new kid goes nowhere.

I don’t mean to suggest that Europeans are any more “civilized” than Americans — only that some sense of relativity is necessary to understand the ideas this movie pretends to be dealing with. It seems to assume, for instance, that having an education guarantees civilized behavior. But when the Supreme Court recently voted unanimously that public-housing tenants could be legally evicted if any household member or guest took illegal drugs — even outside the premises and without the tenant’s knowledge — I’m sure that some educated people, possibly including the justices themselves, considered this an act on behalf of “civilized” folk such as themselves rather than a gift to the sleaziest and cruelest slumlords. I consider it barbaric, just as I consider a recent boast by Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci less than civilized; after trying to eject Somali immigrants from a tent next to the Florence cathedral, she said, “I don’t go putting up tents in Mecca. I don’t go singing Ave Marias or paternosters before the tomb of Muhammad. I don’t piss or shit at the feet of their minarets.” Of course one could debate which is less civilized behavior — performing certain bodily functions in public or lumping a billion Muslims together to characterize the behavior of a few Somali immigrants. Once again notions about civilized behavior are being predicated on unacknowledged class issues.

If bodily functions are important in defining civilized behavior, one might wonder why toilet training is nowhere in evidence in Puff’s cultural conditioning — no toilet of any kind is apparent inside his glass cage. But perhaps the filmmakers assumed that excluding such details was in the interests of their notion of “good taste” — some definition of civilization that they weren’t ridiculing.

My point is that provincial preferences shouldn’t be mistaken for general definitions of civilization. Unfortunately, Human Nature derives nearly all of its laughs, even the best ones, from glib middle-class American platitudes about “nature” and “civilization” that the film wants us to believe are universal truths. So if we laugh are we being civilized or uncivilized?