From Film Comment (July-August 1976). In some respects, I think this may be the best of all my many Journals for Film Comment, but for my readers who feel that my work is sometimes (or often) marred or even ruined by my strident tone, it may also be legitimately regarded as my worst. Among other negative consequences, Truffaut read my comments about THE STORY OF ADELE H. and wrote me an angry letter about them (which can be accessed, along with my response to it, on this site), I suspect (without actually knowing) that my passing comment about Pauline Kael may have sabotaged any hopes I’d had about ever becoming friends with her, and my friend (at the time) Gilbert Adair, cited just before the end of this piece, was furious about the over-the-top way I expressed my displeasure with Charles Barr in Movie. For better and for worse, I think this shows my writing at its most intense. -– J.R.

March 25 (London): A KING IN NEW YORK.Even on a Steenbeck, Chaplin’s penultimate feature and last extended performance has such a naked power of embarrassment and assault that one can see right away why so many have recoiled from it. Chaplin himself avoids any mention of it in the text of his Autobiography; most reports refer to it as a shameful debacle; and even such an indefatigable enthusiast as Bazin virtually threw in the towel. So far as I can gather, only Rossellini — seconded by some of his wilder Cahiers disciples — had the perspicacity in 1957 to call it the film of a free man. Clearly the objections can’t be traced back to any failures of expression: how many films are more expressive than Chaplin’s? No, the discomfort seems to be with the things that are expressed, more autobiographical and candid in their revelations than anything we are ordinarily accustomed to; and without this “personal” reading, the film is almost meaningless.

In other words, Chaplin’s letter of spite and sorrow to America asserts personal indignation — perhaps the least palatable form to an audience, because it is the most honest, consequently the most apt. In place of generalized invective, we largely get Chaplin’s own experience, which includes his complex and ambivalent implication in the American dream: the King’s own silliness in the presence of Dawn Addams. But the horrible taste of the plastic surgery episodes, which immediately derive from this, is not only Chaplin’s transgression, but America’s too; and the charge that most of the film isn’t very funny should be met with the reply that, as at the end of THE GREAT DICTATOR and throughout much of MONSIEUR VERDOUX, there are times when laughter is beside the point. The implication of Chaplin being hounded out of America was that he didn’t deserve to stay; the implication of a KING IN NEW YORK (made four years later) is that America didn’t deserve Chaplin. And maybe it didn’t. How could McCarthy-crazed America have possibly appreciated the lucidity that the film has to offer, which, going beyond Tashlin, reveals the true moral and aesthetic tackiness of the U.S. in the mid-Fifties, without any digestible sweetening? That America in the mid-Fifties had more than this is obvious, and one can look elsewhere to find it. But one can’t go anywhere else to find the devastating accuracy or justice of his last testament.

March 27 (New York): THE STORY OF ADELE H., or GIDGET GOES HEGELIAN. Truffaut’s pretty, non-obsessive postcards about obsession are a gift to the eye in Nestor Almendros’ photography, but a dull bromide to the mind. Apart from offering a veritable film festival to the spectator who wants to wallow in self-pity and call it literary, the camera’s habit of cutting away to another quaintly posed set-up every time the heroine’s perversity starts to become interesting only underlines how steadily Truffaut has been veering away from any serious risks. A crowd-pleaser in the tradition of Chaplin, he has yet to make his VERDOUX or KING because he always looks for the easy way out.

Much as his collected movie pieces (Les Films de ma vie, published by Flammarion last year) exclude all his polemical writing, and his editing of Bazin has tended to follow suit — with comparable implications of historical whitewash — this takes the tang out of its heroine’s madness by giving us a healthy, talented ingenue in place of an actress. Of course, one can understand Pauline Kael believing this to be a great work of art, just as one can understand many American intellectuals believing that Kael is a great aesthetician. Given the right sort of climate and training, anything’s possible, even the Nixon Administration and snuff movies.

March 29: Which brings me to TAXI DRIVER, another Kael favorite. Great Bernard Herrmann score, great performances, the best Scorsese direction to date — turning New York into an expressionist moonscape and another Capital of Pain — all pressed into the service of…what? Check out Paul Schrader’s marathon interview in the March-April Film Comment, which tells you the exciting answer: a transcendental movie about his gun collection influenced by Bresson. But better than Bresson (whom Kael finds “perversely academic”), because it also gives you a simulated snuff movie (Scorsese’s endearing monologue) and an exceptionally arty My Lai massacre sequence — obligatory to all Serious American Films, because all Serious American Films are about America, right? Just as Bresson’s films, according to Schrader’s transcendental mystifications, are about what you don’ t see or hear in them, rather than anything so mundane as their own ingredients.

God forbid anyone should make a serious movie about something a little less all-encompassing and metaphysical than “God” or “Grace” or “America”– like, say, sound or image or Chaplin and America; that’s for cultists. Stick to the Gospel and you’ll be rewarded hugely, as long as you keep it watchable. And TAXI DRIVER is very watchable. But for hip insight into ideology, give me MANDINGO any day.

(A marginal fact about the latter may be of some interest: while seeing it in London in early May -– appropriately double-featured with ROSEMARY’S BABY — an American acquaintance pointed out to me that Susan George’s mulatto baby, visible in the version we saw, wasn’t in the prints she saw in L.A. Could this be because Americans prefer to keep their nightmares in the realm of pure metaphysics? For the record, the baby looks like any other.)

***

April 9: FAMILY PLOT. Hitchcock, on the other hand, has made a movie about his own sexy forms of duplicity and deception, which include sound and image, sumptuous musical scores and cuddly Hollywood types . . . what better subject for him? But to judge from a lot of local remarks, this gem is apparently one of the Master’s lightweights because it doesn’t contain any guilt (unless one discounts the wealthy dowager’s regrets about the past which set the double-plot in motion) or murders or contemporary gloss. Apparently death, sex, and money aren’t as significant as New York City or Watergate unless they’re seen through a stained glass, darkly.

Three separate friends have complained that the sequence with Barbara Harris and Bruce Dern in the brakeless car is “embarrassing”: I’m not sure whether this means corny or old-fashioned or something else, although this clearly wasn’t the experience of the three audiences I saw it with during the first eight days of its run. If by “embarrassing” they mean that it makes its own strategies evident and obvious, I can only concur. In a rare burst of candor, Hitchcock finally places the transcendental where it belongs — in a crystal ball — and devotes his energy to showing us how a thriller works. That the film’s visual structure is witty enough to rhyme its crystal ball with a religious amulet and symbol of wealth (the giant diamond), and to suggest elsewhere that both are like TV screens — so that Hitchcock’s own appearance consists of his video silhouette, behind glass-only helps to show that FAMILY PLOT’s true lucidity (like Lang’s in SPIES or THE 1000 EYES OF DR. MABUSE) is its manner of equating its own narrative devices with its characters’ actions, creating a mirror- surface which lets an audience watch its own responses rather than get lost in them. AII mirrors, to be sure, are potentially “embarrassing.”

And if the devices in question are old-hat or corny, a thin coating of contemporary gloss is all that conceals the same qualities in TAXI DRIVER or ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN behind their “significant” subject matter. From this standpoint, it’s the latter films which are really escapist, not FAMILY PLOT, because the experiences they offer contain practically no self-reflecting mechanisms — merely “food for thought” in the grand old Sunday supplement tradition of Stanley Kramer.

***

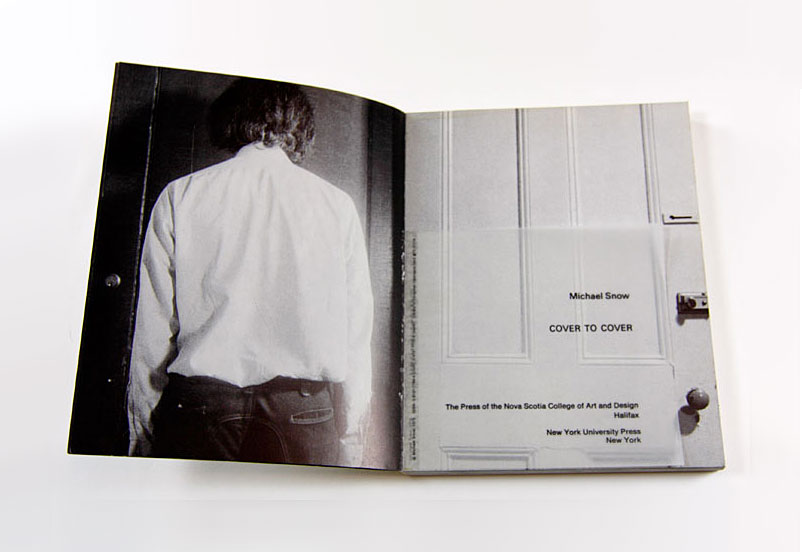

April 12: I purchase a copy of Michael Snow’s Cover to Cover, which, along with the Hitchcock, is the most interesting filmic experience America has afforded me so far this trip. It costs a hefty $12.50 in soft cover, $20.00 in cloth (co-published by the presses of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and New York University), but unlike filmic experiences which cost a fraction as much, you can take it home with you. As with FAMILY PLOT, it is essentially concerned with its own manipulations, but on the other hand it isn’t a movie but a book.

Or is it? A lot of the fascination inherent in this singular object of 320 pages is its curious hybrid nature, halfway between book and film in the experience it offers. Rumor has it that Snow himself regards it exclusively as a “bookish” book, but part of its value as an open work is that it imposes no precise itinerary in how one “reads” it. One can flip through the photographs/pages on either the right or left, forward or backward, or take them more slowly and consecutively — in which case it becomes apparent that the reverse side of each page is a reverse-angle, with the frequent visibility of each camera only foregrounding the processes that much further.

Rather than attempt to spell out the book’s narrative and continuity (which Regina Cornwell has already helpfully done, despite a faulty page count, in the March-April Studio International), l’d rather draw attention here to its playful dialectic between “reading” and “watching,” which includes such “bookish” traits as the upside-down flip-overs on pages 163 and 171, and such pure “movie” tricks as the disappearance of the stray male onlooker between pages 189 and 191. (The pages are unnumbered, alas, so one must count from the cover to reach these examples, as I did.) The ambiguities of such transitions bring to mind another unique hybrid: André Hodeir’s extraordinary jazz composition based on a James Joyce text, Anna Livia Plurabelle (available on the French Epic label, EPC 64695), which explores the differences and relationships between musical and literary logic through an intricate series of jazz pastiches and verbal puns, developed simultaneously. Cover to Cover embarks on an analogous adventure, with pages serving as the equivalent of film frames, in an exhilarating exploration into the nature of narrative continuity in both mediums.

***

April 15: My first opportunity to re-see PLAYTIME in over three years comes courtesy of Lucy Fischer’s undergraduate film course at NYU. In Europe, the film remains tied up in litigation due to Tati’s bankruptcy and ensuing misfortunes — such as his having to auction off the original negative-and even the last time I saw it was at a private screening. I realize that most people couldn’t care less about such information (or the fact that, according to a Paris friend, the original negative of Bresson’s DIARY OF A COUNTRY PRIEST can no longer be traced), but it does seem worth noting that PLAYTIME is still available in 16mm in the States. So it’s with an unnatural amount of expectation that I return to a film which I consider to be the most remarkable accomplishment in mise en scène in the history of narrative cinema.

I’m not trying to traffic in hyperbole here, so I’ll stick to specifics. The film’s first hour is markedly inferior to its second — however useful much of it may be as preparation — and the sequence at the gadget exhibition mainly looks ugly and loosely structured now, particularly in relation to the rest. I also find myself preferring, in retrospect, the separate version of the sound track Tati prepared for France (which also contains a lot of English), if only because I recall the former seemed even more abstract in its vocal sonorities and stresses, at least to me. But in terms of the systematic control of all its elements, the long restaurant sequence and its aftermath does more than surpass everything else I know in narrative cinema for its complex organization; it leaves the rest far behind. One can speak of Mizoguchi for [what Rivette calls] “modulation,” IVAN THE TERRIBLE for compositional rigor, GERTRUD for rhythmic control, or RULES OF THE GAME for social density, and early Welles for narrative fluency; but for the sheer number of elements that are organized in single shots and their accompanying sounds, this hour of film has no competitors at all.

And with the possible exception of Snow’s non-narrative LA RÉGION CENTRALE, which I’ve experienced only once, I know of nothing in cinema which physically exhausts me as much. Fifteen minutes after it’s over, I find myself inadvertently crashing into a wall like one of Tativille’s inhabitants, still overwhelmed by the notion that any slab of sound and image — reality included — can be so richly orchestrated. The crucial catalyst, I’ve come to feel, is the music played in the restaurant by two successive orchestras, then sung by a chanteuse who is later joined by all the people present — an element which ultimately helps one to deal creatively with Tati’s overload of invention by supplying one with a rhythmic base to work from. Thanks to this music, each set of visual options offers a different choice of rhythmic trajectories in relation to the underlying pulse, a number of evolving figurations through which spectators can join Tati in charting out their own choreographies, improvising their own organizations of emphasis in relation to the director’s massive “head arrangement.”

What other film converts work into play so pleasurably by turning the very acts of seeing and hearing into a form of dancing? And what is the glorious triumph of PLAYTIME’s ending but the implications stemming directly from this, the capacity to make “fantasy” and “documentary” wholly compatible — a carousel of traffic, and a tilting window-pane reflection causing bus riders to rise from their seats, both dovetailed effortlessly into “real” shots of traffic and Orly airport at night?

Yet facts remain facts. Somehow I must reconcile this indecent experience with acquaintances who remark, “I don’t think Tati’s all that funny” or “PLAYTIME’s okay, but it’s not as good as TRAFFIC,” or make meaningless comparisons with Chaplin or Keaton, which is rather like comparing a Brueghel landscape with a portrait by Rembrandt or Van Dyck. I have to inhabit a universe where, in a temple of aesthetic enlightenment like Movie, Charles Barr can write (in the seventeenth issue) about the “formal and thematic” unity Blake Edwards can bring in THE PARTY “to what might — very superficially — appear just a series of incidents and gags strung out to feature length. Like PLAYTIME, for instance,” and where countless critics who claim to be interested in radical innovation won’t give this film the time of day.

But the film remains, and the proper investigatory work on it has scarcely begun. In the meantime, I can only look forward with comparable eagerness to Rivette’s DUELLE, the first feature in his four-part SCÈNES DE LA VIE PARALLÈLE(formerly known as LES FILLES DU FEU), which has already had the honor of being rejected by the Main Selection at Cannes, and which may or may not be visible in Paris by the end of May. My two collaborators on the Rivette interview in the September-October 1974 Film Comment — Gilbert Adair and Lauren Sedofsky — have seen it at a private screening, and both describe it as his greatest achievement to date; whether or not I’ll agree with them will have to wait until my next Journal.