Commissioned by New Lines magazine the day that Godard died (September 13, 2022), and published by them without this title two days later. — J.R.

“He wasn’t sick. He was simply exhausted,” someone close to Jean-Luc Godard told the French newspaper Libération. But not so exhausted that he couldn’t confound his public, including his fans, one last time, by deciding to end his life by assisted suicide — that is to say, to end it nobly, willfully and seriously, even existentially, rather than fatefully and inadvertently.

Godard was hated as much as Orson Welles by the commodifiers who could find no way of commodifying his art, of predicting and thereby marketing his next moves as they could with a Woody Allen or an Ingmar Bergman or a Federico Fellini. And in the end he fooled us one last time by following his own path rather than ours. Was his way of dying a selfish act? Yes and no. It yielded an honest and considered end rather than an involuntary one; it tells us who he was (and still is).

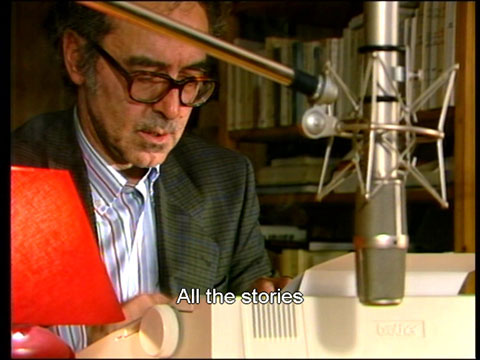

I first encountered Godard’s work when I was 17 and saw À Bout de Souffle (Breathless, 1960) in New York. But I didn’t meet him in person until 1972, when I tried to interview him and Jean-Pierre Gorin in Paris about their co-directed Tout va bien (Just Great). When I met them both at the Cinémathèque at Palais de Chaillot, Godard politely canceled the interview because he was still on the mend from his auto accident (which I later learned sexually wounded him, but also led to him meeting his final partner and eventual next-door neighbor in his native Switzerland, Anne-Marie Melville). Eight more years would pass before I finally interviewed him for Soho News about Sauve Qui Peut (la Vie) (Every Man for Himself, 1980), during a limo ride that took us from midtown Manhattan to LaGuardia airport, where he was flying to the Toronto International Film Festival, and which enabled us to have our first conversation. Our second, third, and fourth conversations — more precisely, all the remaining ones we would ever have — had to wait until we met at that same festival 16 years later.

I first learned that he liked my writing through a colleague, Serge Daney, in 1982 (after Godard had read my reflections on Welles in Trafic, the new French quarterly that Serge had just launched) and then from Tom Luddy in 1988 (who phoned me at Godard’s request to thank me for my review of his King Lear, which Luddy had produced). Then, in 1995, Godard had invited me to be on a panel at the Locarno International Film Festival about his still-in-progress video series Histoire(s) du Cinéma. I was serving at the time on the New York Film Festival’s selection committee and was permitted to shirk my duties there for a weekend — long enough to be on the panel (which Godard didn’t attend), but not long enough to travel to Rolle, Switzerland beforehand to preview with Godard chapters 3a and 3b, devoted to Italian Neorealism and the French New Wave.

Slightly over a year later, Godard brought those chapters and a more recent one — 4a, on Alfred Hitchcock — to Toronto to show them to me in his hotel suite, which led to me interviewing him a second time. At the same festival in Toronto in 1996, where Godard was publicly showing For Ever Mozart (for me the absolute worst of his late features, which I had successfully argued against the New York Film Festival showing — although we thankfully didn’t discuss this film in our interview), he praised me extravagantly during his press conference, comparing me to both James Agee and André Bazin. We met immediately afterward, for our last interview session, and when I remarked, “That was really nice what you just said about me,” he replied, “I hope it helps you more than it hurts you, considering whom it’s coming from.”

I managed to spend several hours with him in Toronto that year on a more casual basis, and one thing I discovered about him was how often he liked to keep people at a certain distance, during which time he often seemed to be lost in his own thoughts but was actually quite observant of what was happening around him. I suspect that this had something to do with a certain resistance towards being an all-purpose guru at every moment, even though he played that role to the hilt at other times. At one juncture, during a meeting he had with ECM Records CEO Manfred Eicher, I recall him idly pouring ketchup into a glass of water, stirring it with a spoon, and then drinking the results, as if to emphasize his total independence from whatever was happening around him. It was similar to the comic persona that he liked to play, or play with, in some of his features, notably Prenom: Carmen (First Name: Carmen, 1983), Soigne Ta Droite (Keep Your Right Up, 1987), and King Lear (1988).

Our mutual friend Rob Tregenza (whose third feature he was producing at the time) was present at many of those casual moments, and when I spoke to Rob at one point about how the films of Robert Bresson didn’t function well on video because video foregrounds sound over image while film does the reverse, Rob argued that a good sound system might change this. Godard seemed to be away on the moon during this discussion, but a day later, when Godard and I were chatting alone, he suddenly and unexpectedly brought up this previous discussion, siding with me rather than with Rob.

On some matters he was inflexible. My efforts to convince him to see François Truffaut’s La Chambre Verte (The Green Room, 1978) and Michelangelo Antonioni’s Al di là Delle Nuvole (Beyond the Clouds, 1995) were as fruitless as my argument that the plot of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man doesn’t include a real-life miracle but one that Hitchcock and his screenwriters invented; in all three matters his critical positions regarding Truffaut, Antonioni, and Hitchcock were firmly settled, not subject to any second thoughts or corrections. This stubbornness I associated with the Germanic, Goethe-like side of his personality — which also comes to the fore in his video JLG/JLG — Autoportrait de Décembre (JLG/JLG — Self-Portrait in December, 1995) — and the funereal pronouncements it gave rise to, not the more slippery French side that seemed subject to constant and playful revisions.

My last physical encounter with Godard was at the press conference at Cannes in 1997 for his recently completed Histoire(s) du Cinéma. I was seated in the audience, near the front, after presenting Godard with a copy of my new collection Movies as Politics, and having received a bilingual pamphlet pairing my “Trailer for ‘Histoire(s) du Cinéma’ ” with Hollis Frampton’s “For a Metahistory of Film” (which had also appeared in Trafic). Godard deferred to me once or twice during the press conference (e.g., asking me to furnish the title A Place in the Sun when his memory failed him), and this was truly the last of our exchanges — apart from my friend Nicole Brenez, his recently acquired picture consultant, bringing one of my more recent books to him in 2019.

But in 2015, in Zagreb, at Tanja Vrvilo’s ninth annual “Movie Mutations” event (named after an anthology I co-edited with Australian film critic Adrian Martin), I was able to hang out with Fabrice Aragno, Godard’s cinematographer and all-around technical assistant since 2004. One of the first things he said to me was that he didn’t consider himself a “Godard fan” — his own aesthetic preferences were closer to Antonioni and Kiarostami — but that he loved “working with Jean-Luc.” I also learned from him that after Godard booked two passages on the cruise ship Costa Concordia for both himself and Aragno for Film Socialisme, he decided not to go himself on the second passage, and instructed Aragno to go alone and either shoot his own material or shoot nothing, depending on his own preferences — but refused to give him any instructions about what he might shoot. And Aragno wound up shooting a good deal of material that Godard used in the film. For Adieu au Langage (2014), he devised the 3-D system that was used with Godard’s input and shot a test reel of 3-D visuals and sound separations (a fascinating document that he screened in Zagreb), and the little boy and girl viewed periodically in the film are his own children.

Even though mainstream media has branded Godard as a grouch and an obscurantist as often as it chided Welles for his weight (which even alleged friends such as Gore Vidal tended to harp on), the real mainstream crime of these artists, apart from being unapologetic intellectuals, was their unpredictability, which, as I’ve suggested above, made them relatively unmarketable, at least when they were alive. For all the love lavished by Quentin Tarantino and others on Bande à Part (Band of Outsiders, 1964), it’s important to recall that this movie failed abysmally at the box office, both in France and the U.S., when it was first released — for the same reason, I would maintain, that Truffaut’s Tirez Sur le Pianiste (Shoot the Piano Player, 1960) flopped: for its switching back and forth relentlessly between tragedy and farce, confusing genre and marketplace identities and signals as well as our emotions — and his own — in the process. Arguably Breathless also did this mixing of moods and modes, but in a less affectively challenging fashion, by remaining always a thriller — or at least seeming to follow this consistency. (As Godard once argued, when great films succeed commercially, it is often because of a misunderstanding. This might have been the case with Breathless.)

After Godard became politically radicalized in 1968, he took drastic steps to alienate his cinephile fans while forging less pleasurable forms of ranting and theorizing. This was embraced by some academics who found the results “teachable” in an armchair leftist fashion, but for Godard it was chiefly a way of shedding his skin and restarting his career. In contrast to the more humanist aims of his strongest political films — Ici et Ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere, 1976) and Numéro Deux (Number Two, 1975), and two series also made with Anne-Marie Miéville for French TV in Grenoble (both broadcast in ways that undermined many of their objectives) — were the non-humanist Vent d’Est ( Wind From the East, 1975) and Vladimir et Rosa (1976),which the academics tended to prefer, perhaps because they were easier to diagram on a blackboard. Yet it seems significant that Godard avoids referencing these films in his Histoire(s). By the time he returned to making masterpieces, albeit difficult ones, such as Passion (1982) and Nouvelle Vague (1990), he had lost his mainstream champions (“The party’s over,” concluded the New York Times’ Vincent Canby of the latter film), many of whom tended to link his commercial failures with supposed character flaws.

What made Godard’s international influence from the 1960s onwards as huge as Welles’ from the 1940s onwards was a function of both his framing and his editing — added to which was his activity as a film critic, especially when this overlapped or coincided with his activity as a filmmaker. Godard and his critical colleagues comprised the first generation of cinephiles who treated film history as part of cultural history — an obvious approach today, yet one of the things that made Susan Sontag so controversial in the 1960s was the fact that she was the only visible New York intellectual to take this approach. And indeed, this critical position, even when it was misunderstood and/or vulgarized, may have changed the face of modern cinema as much as the use of jump cuts in “Breathless” or Godard’s capacity throughout most of the 1960s to make his films resemble global newspapers.

To function as a film critic through one’s filmmaking was a talent shared by Jacques Rivette and, to a lesser extent, Luc Moullet, but not by other critics at the French magazine Cahiers du Cinéma such as Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, André Téchiné and Olivier Assayas. Nor was it practiced by the Hollywood “brats” influenced in diverse ways by Godard’s example: Woody Allen, Peter Bogdanovich, Francis Ford Coppola, Brian De Palma, Paul Schrader and Martin Scorsese, all of whom substituted homages for critiques — rubber stamps of imitation and approval that did nothing to inform our appreciations of what they were duplicating. (Curiously, Alain Resnais had the same sort of critical intelligence as a filmmaker as Godard, even though he never wrote any criticism; his particular slants on 1940s melodramas and 1950s MGM musicals in his own films are always personal commentaries on them, not mere copycat references.)

Back in Toronto, Godard admitted to me that much of his on-screen criticism was done unconsciously and that apart from a few obvious references that resembled the homages of the movie brats, his overall critiques of German Expressionist cinema in Alphaville, which I’d written about in my first article for Sight and Sound, only became apparent to him afterward — something he also acknowledges in chapter 3b of Histoire(s), when he superimposes shots from Fritz Lang’s Destiny (1921) over shots from Alphaville. (Or is it vice versa?)

Given Godard’s many incidences of thievery during his youth and his frequent practice in his subsequent work of using unattributed quotations, I think his unusual talent for plundering various art forms in his films, conscious or unconscious, had a lot to do with what made his creativity special. That is to say, his “thefts” were never impersonal but always critical and personal forms of appreciation, such as his appropriations of German Expressionism and its derivatives (e.g., Akim Tamiroff from the films of Welles, Orphée from Jean Cocteau) in Alphaville. It’s worth adding that some of Godard’s more selfless gifts — such as his anonymous financial assistance to Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet (on Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach) and Jean Eustache (on Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes), and his producing (again without credit) Rob Tregenza’s Inside/Out — were as important as his thefts; they might even be described as tantamount to picking his own pockets.

In striking contrast to the sweet and sour reflections that we read or hear from American journalists about Godard’s death, grumbling almost as much as they say Godard did, Libération brought out a celebratory 28-page special issue in color devoted exclusively to Godard only a day later, including contributions from such Americans as Jim Jarmusch and Daniel Mendelsohn. The fact that the box office “performance” of Godard’s late features was reportedly even worse in France than it was in the U.S. only proves that marketplace value has little or nothing to do with the love of art, and that there’s no way of gauging the latter via the former, especially insofar as the intensity of the love and the qualities of the audience experiencing and expressing it aren’t even remotely quantifiable.

I suspect that the future final look at Godard that many of us will have and remember is Mitra Farahani’s startling À Vendredi, Robinson (See You Friday, Robinson), which just opened in Paris (and which I was lucky enough to see last summer at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna). A staged internet encounter between two nonagenarian New Wave pioneers — Jean-Luc Godard of the French New Wave and Ebrahim Golestan of the First Iranian New Wave — who meet one another only digitally, thanks to the filmmaker (an Iranian woman based in Europe), this abrasive, Godardian feature, whatever its intentions, has a lot to say about the class that Farahani, Godard and Golestan all belong to: the high bourgeoisie. The dialectically contrasting self-portraits that emerge from the weekly exchanges (which all take place on Fridays — thus the title, derived from one of Godard’s sign-off statements) are brutally different in both décor and styles of self-presentation: Golestan, director of Brick and Mirror (1964) and The Iranian Crown Jewels (1965) — both masterpieces that brilliantly skewer the greed and pretensions of the ruling class — presents himself like a sultan in palatial surroundings, clearly enunciating all his arguments; Godard presents himself simply and modestly, as if he were a peasant, even though what he has to say about his distrust of language sometimes borders on the incomprehensible.

I suspect that the wisest thing Godard ever said to me came in our first interview, in 1980. “People like to think of themselves as stations or terminals,” he said, “not as trains or planes between airports. I like to think of myself as an airplane, not an airport.”

I asked him, “So that people should use you to get certain places and then get off?”

“Yes. I’ll work much more on that in my next film.”

As with many of Godard’s pronouncements, I’m not entirely sure I know what he meant by this. But what I can use is perfectly clear. It’s the fact that texts and movies are vehicles that take us places, and the destinations of those who make them don’t have to be the same as the destinations of those who climb into those vehicles. I’m a maker of some of those vehicles, which others use to take them where they (not I) want to go, and I’m someone who takes the vehicles of others (Godard’s, for instance), which take me where I want to go. I think that’s more or less what poetry does.