The fifth chapter of my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (Chicago: A Cappella Books, 2000). As James Naremore aptly notes about my work in his collection An Invention Without a Future: Essays on Cinema (Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 2014), I have revised my attitudes towards watching films on home video formats considerably since I wrote this over a decade and a half ago. -– J.R.

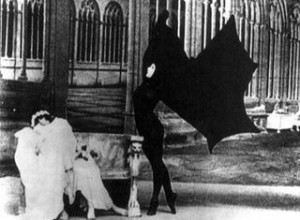

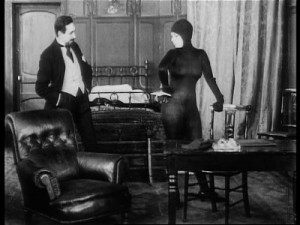

In 1998, Water Bearer Video issued in a boxed set of four cassettes the complete ten-episode silent French serial Les vampires. Directed by Louis Feuillade in 1915 and 1916 and starring the great actress Musidora as the mysterious Irma Vep, this monumental and exciting crime fantasy is one of the key works in the history of cinema — seminal in its influence on moviemaking as a whole, and to my mind considerably more watchable, pleasurable, and even modern from certain perspectives than the contemporaneous long features of D. W. Griffith, The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance. Yet astonishingly, this major work had been unavailable in the United States for over eighty years, ever since it ran commercially as a serial in American movie houses; apart from a few exceptional archive and festival showings from the sixties onward, not a single episode was distributed in any form. Maybe this was due to a problem regarding copyright and was not simply a matter of protracted neglect; in any case, as a consequence of this unavailability, American film history courses routinely elided Louis Feuillade’s work from their syllabi — an oeuvre comprising several hundred films, including several other serials, some of them of comparable interest: Fantomas (1913–14), Judex (1916), La nouvelle mission de Judex (1917), Tih Minh (my own personal favorite, 1918), Barrabas (1919), and seven lesser known serials of the early twenties. (Shortly before Les vampires became available on video in the United States, it achieved a certain amount of public currency through the release of Oliver Assayas’s wonderful 1996 feature Irma Vep — a comedy about a contemporary French remake of Les vampires starring Hong Kong actress Maggie Cheung that contained a few short video clips from the Feuillade serial.)

When I taught a semester of silent film history at the University of California, Santa Barbara in the early eighties, I was shocked to discover that not a single one of my predecessors had ever included Feuillade in the syllabus. In order to have done so, they would have had to rent, as I did, an hour-long episode from Fantômas that was available in 16-millimeter from the Museum of Modern Art — not an ideal solution, but the only possibility unless one had access to prints or videos from abroad. By the late eighties I had a VCR that allowed me to play European videos on an American monitor, and after I finally obtained a video of Les vampires from abroad, I showed a few early episodes in a film theory course I was teaching at the School of the Art Institute in 1995, and discovered to my delight that the film was every bit as fascinating and engrossing to my students as it was to me.

So the eventual release of Les vampires on video in the United States in 1998 was major news in the film world, and even more gratifying, major sectors of mainstream media treated it as such. In Time magazine, critic Richard Corliss devoted a special story to the video release, calling it the major film event of the year, and a subsequent article appeared in the Arts and Leisure section of the Sunday New York Times. By early 1999, and perhaps sooner than that, it was a routine matter to come across boxed sets of Les vampires in mainstream video stores; thanks to the efforts of Corliss and others, Feuillade’s masterpiece had triumphantly entered the mainstream of American culture and commerce — or, more precisely, re-entered that mainstream for the first time since the teens. And even though the likelihood remains remote of this leading to the availability of actual prints of Feuillade serials in the United States, it’s heartening to discover that such a major cultural gap can eventually be filled.

Why did it take eighty years for most people to realize that such a gap existed in the first place? One factor is the different discourses found in at least three separate sectors of American film culture -– the mainstream, the film industry, and academia — each of which tends to screen out one or two of the others. Although film industry jargon has increasingly entered the mainstream in recent years thanks to the infotainment of magazines like Premiere and Movieline and TV shows like Entertainment Tonight, trade publications such as Variety and Hollywood Reporter still typically speak a somewhat different language from the mainstream press, and the language of academic film studies exists far beyond the borders of either. Indeed, the divisions created by theoretical jargon are so substantial that they can’t be restricted by any means to American film culture. When I was living in Paris in the late sixties and early seventies, endless debates were being waged in the pages of the two major film magazines, Cahiers du cinéma and Positif, about the terminologies employed by film critics under the sway of Louis Althusser and Jacques Lacan, and comparable battles took place in such British magazines as Sight and Sound, Movie, and Screen when I was living in London in the mid‐seventies. Even today, some of the residue of such debates persists in various forms, though it is still possible for a French or English film theorist to speak on occasion within a relatively mainstream forum — a situation that remains virtually unthinkable in America.

The splintering effect of these three separate discourses in American film culture guarantees not only the absence of a single community with common interests but the present impossibility of conceiving of such a community. Instead of a public forum, what we all share is essentially the same multimillion‐dollar ad campaigns designed to move the same limited corpus of products. Some academics may have gotten the word about Les vampires becoming available on video — although I know a few sophisticated professors who found out a few months later than the readers of Time — but there’s no question that they’re every bit as inundated with material about Titanic, Saving Private Ryan, and The Phantom Empire as everyone else. And though all we share is a discourse of promotion — which none of us entirely believes in, though none of us can avoid it — the possibilities for using this discourse as a means of communication between individuals with common interests is extremely limited. Turn to most movie reviews and entertainment news and you see the implications of those limitations in all their force.

The fact that the film cultures of France and the U.K. (to cite only two examples) are vastly more interactive and interconnected than ours can be attributed to a good many factors, ranging from government- supported institutions (such as the Cinémathèque Française and the British Film Institute) to the smaller size of these countries, not to mention an overall centralization of resources. A film critic from Paris or London who wants to watch the shooting of a studio film has to travel to the suburbs, but a film critic from New York who wants to do the same thing generally has to fly to the West Coast. Moreover, a French or British film academic is likely to be in closer proximity to the resources of Paris or London than a film scholar in Iowa City, Iowa or Madison, Wisconsin is to either New York or Los Angeles.

In some respects, the film culture in England can be interactive to a fault: when I lived in London, I was shocked to discover that some film teachers were so dependent on the film extracts made available by the British Film Institute that they didn’t always bother to see the complete features they were extracted from. For instance, I used to chide a friend who taught the “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” number from Gentlemen Prefer Blondes — a respected contributor to Screen and Screen Education — for her ignorance about and relative indifference to the film as a whole. And the extreme factionalism found in the film communities of both England and France has had its crippling aspects as well — not only partisans of Cahiers du cinéma who refuse to read Positif (and vice versa), but enemies of Sight and Sound who have constructed elaborate histories of English-language film criticism that are shaped and inflected by the unstated determination to exclude references to everything that magazine ever published. (The original edition of Pam Cook’s The Cinema Book — I haven’t yet seen the updated version — is one such example.) And after the departure of Sight and Sound’s longtime editor Penelope Houston, this kind of neo-Stalinist suppression became reconfigured after anthologies of the new Sight and Sound started to appear; henceforth, it became acceptable for Sight and Sound to enter the history of English film criticism, but only the post-Houston version of that magazine. In other words, sustained turf wars in both England and France lead to highly skewed accounts of the history of film criticism, not to mention film history in general.

One also has to factor in the less marginalized status of cultural events and intellectuals in the public life of most European countries. In Italy, intellectuals like Umberto Eco write regularly for the daily newspapers (as did the late Italo Calvino), and most of the articles by Roland Barthes comprising Mythologies originally appeared in mainstream French magazines such as Le nouvel observateur. In 1992, I participated in a highly specialized conference on Orson Welles in Rome attended by about fifty people, the sort of event that probably wouldn’t have merited even a mention in the local press if it had occurred in New York, Los Angeles, or Chicago; in Italy it was treated as major news and reported extensively in national magazines and newspapers. Pretty much the same thing happened in 1999 when I participated in two Welles‐related events at the Munich Film Archive for a few hundred spectators.

***

In the past, a university education was the best or at least the most typical way of acquiring some knowledge about what an art form had to offer. It wasn’t the way I pursued my own self‐education about film history, because when I started out as a film critic in the late sixties and early seventies, I had already reached the end of my own formal education in literature, and the opportunities for studying film academically in the states at that time were few and far between. I had to opt instead for a program of self‐education carried out through reading and attending films in New York, Paris, and London. This is where the special rewards of the Cinémathèque Française and the British Film Institute became apparent to me. In the seventies the former offered six to eight film programs a day at two auditoriums at opposite ends of Paris, comprising a more rich and diversified survey of film history than could — or still can — be found in any American institution; it was this same adventurous programming, spearheaded by the Cinémathèque’s remarkable cofounder, Henri Langlois, that had educated the directors of the French New Wave in the fifties. (Today the same institution has several screening sites in Paris and a good many seminars in addition to film programs.) And even though London’s National Film Theatre was more comparable to New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the British Film Institute also published two first-‐rate magazines, both of which I worked for, as well as perhaps the best reference library of film books and periodicals to be found anywhere. (Back then, this library was available to every paying member of the National Film Theatre, which operated like a film club. More recently, it became much harder for members to gain access to it; the two magazines merged and became taken over by individuals whose knowledge of film history was comparatively meager; and today, in many respects, the British Film Institute, though more responsive to the interests of film academics, survives as a pale shadow of what it was until the early eighties.)

These were the main unofficial “film schools” I attended, either as a customer or as an employee, during my many years of living abroad. But prior to that, and for better and for worse, a university education had a lot to do with my sense of what the greatest literature, painting, and classical music consisted of when I was in my mid-twenties.

Although I can’t speak with any authority about whether one can still learn this kind of information about painting and classical music from an American university, I’m quite confident that the chances of encountering canons devoted to literature and film in American universities nowadays are relatively low, because canons themselves are regarded with a great deal of suspicion. In English and literature departments, a mistrust of canons devoted mainly to the works of “dead white males” has clearly diminished the possibility of teaching literature from a literary standpoint; the social sciences have taken over the study of fiction and poetry to a crippling degree, and in a way this has only completed the damage often done in grammar school and high school by neglecting to enforce grammar for related ideological reasons. Some perceptive recent remarks by Michel Chaouli, assistant professor of German and of Comparative Literature at Harvard, in the Times Literary Supplement, are telling:

The wider the range of objects of study, the more specific and specifically policed the style of presentation becomes. This may be one reason why in our graduate curriculum the literary canon is being inexorably displaced by a rather narrow theoretical canon. If during the reign of the literary canon one lived in fear of having one’s work labeled “trivial”, indebted to the notion of the romantic genius, but rather to devote them-selves to studying the ordinary without abandoning the value of value. But given the workings of our field, a democracy of objects of study may easily be vitiated by an aristocracy of subjects. The trade-off is quite clear: the more ordinary the object of inquiry, the more extraordinary the critic; all the cultural capital that is given up in choice of object flows back in the breathtaking creativity with which meaning can be made to appear anywhere. The romantic genius returns, this time not as poet, but as critic. (1)

_________________________________________________________________________________________

1. “What Do Literary Studies Teach?: A Vast Unravelling,” by Michel Chaouli, Times Literary Supplement, February 26, 1999, p. 14.

As for film canons, the popularity of auteurism in seventies film studies took a nosedive once the ideological construction of authorship started getting interrogated by writers like Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault — writers who, as Chaouli implies, became canonized, along with Louis Althusser, Jacques Lacan, and others, at the same time that filmmakers and their works were rapidly becoming decanonized. Although the demurrals of these writers and others were certainly worth paying attention to, the increasing inclination of American film studies to favor approaches based on the social sciences and to mistrust aesthetics made the erection of film canons a much more precarious undertaking, with the lamentable result that most film academics essentially gave up on the activity. Unless the film in question figured as a centerpiece in an important theoretical text — which was the case, for instance, with Young Mr. Lincoln, canonized as a collective text by the editors of Cahiers du Cinéma that appeared first in Cahiers du Cinéma no. 223 (1970), then in English translation in Screen vol. 13, no. 3 (1972) and numerous subsequent academic anthologies — it often couldn’t find a privileged place in a classroom.

This didn’t mean, however, that a certain amount of de facto canonization didn’t continue to creep into film studies by the back door. An increasing interest in the study of melodrama, for instance, led to the singling out of such films as Mildred Pierce, Now, Voyager, and Imitation of Life as key texts, and because the latter of these films was directed by a former auteurist favorite, Douglas Sirk, a modified form of auteurism might still be employed when a Sirk film got discussed in class. But the increasing distrust of supporting aesthetic canons, even after it eliminated or at least modified many of the claims of auteurism, generally led to the practice of viewing films as symptoms of social formations, economic conditions, or psychological predilections, rather than as aesthetic objects. And since the mainstream continued to go about its promotional business in elevating certain films as aesthetic objects, the relation of academic film study to this process became mainly passive and complicitous, in spite of its better impulses. The desire of some professors to get large enrollments, for instance, has encouraged them to validate such topics as the mythological underpinnings of the Star Wars cycle — which have already been extensively validated in George Lucas’s own press campaigns — rather than interrogate, say, the ideological functions of these myths in launching wars, which might cut back on those same enrollments.

In some respects, the “democracy of objects” and “aristocracy of subjects” alluded to by Chaouli — corresponding to a mistrust of aesthetic hierarchies and a dependence on (mainly European) theoretical models — yields not so much an absence of canons when it comes to film studies as a canon that exists by default, what Harold Bloom calls a survivor’s list:

We have not had an official high culture in this country since about 1800, a generation after the American Revolution. Cultural unity is a French phenomenon, and to some degree a German matter, but hardly an American reality in either the nineteenth century or the twentieth. In our context and from our perspective, the Western Canon is a kind of survivor’s list. (2)

_______________________________________________________________________________________

2. Harold Bloom, The Western Canon, New York/San Diego/London: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1994, p. 38.

Bloom is of course referring to a canon of literary works rather than films, but there’s enough carryover in attitudes to make portions of his argument applicable. There was never an “official high culture” relating to film in this country, but for a brief period in the sixties there was a faint evocation of the possibility of one, largely imported from France, that combined a reevaluation of Hollywood cinema with a kind of modernist reevaluation of contemporary cinema tied to the French New Wave. It was enough of an evocation, at any rate, to strike terror in a number of academic orthodoxies, and the fact that it was occurring around the same time that many film studies programs were being established produced a number of contradictory effects. A skeptical form of auteurism began to enter the academy, but the political and ideological qualifiers to this auteurism quickly began to overtake them, so that a canonizing of theoretical texts became paramount and a canonizing of filmmakers and films became secondary. Then, over time, thanks to a growing mistrust of aesthetic canons as well as aesthetic theories, the treatment of films as social, economic, and psychological symptoms began to dominate. Effectively this meant that the aesthetic positions of mainstream critics were allotted a clear and unchallenged playing field; each sphere of criticism was expected to stick to its own turf and mind its own field, and the most pronounced form of interchange between the two spheres was a growing disdain and mutual lack of respect. What might have figured in a more interactive film culture as some sort of dialectic and polemical struggle became instead a kind of reciprocal alienation.

Again and again, one witnesses in contemporary film courses a weary acceptance of the priorities of the media as an unalterable fact of nature, priorities that have to be adopted rather than questioned or undermined in order to solicit the interest of students; and the very same priorities, alas, hold with equal firmness in publications such as The New York Review of Books. The philosophy behind this attitude appears to be that we can alter our culture only by boring from within; and the fact that George Lucas operates according to the same principle isn’t very encouraging if one considers that the resources at his own disposal to “bore from within” are astronomically greater than that of all the film professors in the world combined.

***

Although I’ve been suggesting throughout this chapter that academic film study often operates in a state of denial, I haven’t yet broached the single area where that denial can be said to be most cripplingly in force: the profound difference between watching a film and watching a study of films on film a luxury that most of the film departments in this country can no longer afford. With a few notable exceptions — which usually turn out to be the most sophisticated as well as the best endowed film study programs and departments — films are now screened and studied principally on video, laser disc, and DVD formats. Most professors have little choice in the matter, so it would be pointless to blame them for pursuing this alternative. Where denial comes into the picture is in the commonly held pretense that watching a video, laser disc, or DVD is essentially the same thing as watching a film.

In other words, expediency has unconsciously created and subsequently intensified an ongoing imposture. It’s a demonstrable fact that video and film are not even remotely interchangeable in relation to such basic factors as light, projection, definition, shape and texture of image, and interaction of sound and image — to start with only a short list, and overlooking the problem of cropping and scanning on video that eliminates roughly a third of the image of most anamorphic widescreen films and usually alters the editing of those films as well. Indeed, the fact that film critic Fred Camper — who reviews films with some regularity for the Chicago Reader and publishes film criticism in many other outlets — categorically refuses to preview any film on video stems directly from this important distinction. For the same reason, Camper refuses to show films on video whenever he teaches film courses.

But Camper is the exception, not the rule, in film reviewing and film teaching alike. Given the logistical difficulty of proceeding otherwise, most other film teachers wind up showing films on video to their students and then discussing them as films. Even if they want to discuss what they show as videos and not as films, the corpus of available written material about this distinction is too minuscule to make such an approach practical for most film academics. As I note in Chapter Eight, the late French film critic Serge Daney — who wrote interestingly and at length about the ramifications of watching films on television, and who might provide an interesting starting point for a pedagogical way of dealing with some of the problems involved — has not yet been translated into English. And without a theoretical or practical guide for coping with the differences between film and video, film teachers typically wind up circumventing and ignoring most of those differences in order to concentrate on other matters: alienation in a nutshell. In the not-too-distant future, when film may disappear entirely from what we now refer to as movie houses and may survive only in museums and other specialized institutions, the theoretical work done on the phenomenology and aesthetics of film throughout the twentieth century may be ground underfoot in favor of less differentiated standards. Indeed, if video aesthetics eventually replace film aesthetics, this may only become fully understood and theorized after the present transitional period is over, when the confusing impasse of treating the two media as interchangeable is no longer seen as a necessary evil.

It’s a truism that the technological and material limitations of the equipment used in teaching tend to define the limitations of what’s being taught, so it doesn’t seem accidental that the relative disfavor in recent years of aesthetics in academic film study and the increasing popularity of the social sciences coincides precisely with some of the conditions of watching films on video. By the same token, one could argue that the interest in stars over directors that is already emphasized in the mass media has often been reflected in academic film study for the same reason — because stars are more immediately visible and recognizable on TV screens than directorial styles. And in the case of certain films where the material relations of sound and image are crucial — such as the features of Robert Bresson and many experimental works — it can easily be argued that the value of such works is effectively eliminated on video. In Chapter Six, I discuss the overwhelming success of a recent touring retrospective of Bresson’s films in 35-millimeter prints. Most of these films lose their aesthetic impact on video, which obviously had some connection with this success: attempting to “teach” Bresson on video is a losing proposition from the start, making the impact of his films on film a good deal stronger than it might have been otherwise.

In other words, although academic film study should ideally focus on the most salient attributes of films that are ignored in the culture at large, the logistics of teaching film courses usually obliges most teachers to replicate the same omissions and curtailments and perpetuate the same problems. However useful videos, laser discs, and DVDs are as tools in analyzing sequences, their omnipresence in film departments as textual substitutions for film are as crippling in some ways as using Cliff’s Notes instead of texts in literature courses. The fact that many students nowadays can’t even identify what they’re watching as a projected film or a projected video or laser disc — something I’ve heard about repeatedly from teacher friends as well as observed firsthand — is symptomatic of the kind of alienation that the surrounding culture has already imposed on education.

***

Like it or not, one of the major activities of any film culture is a labeling of certain films as good and others as bad, and no academic approach can eliminate this activity entirely. At best it can hope to offer some critical training in understanding that activity; at worst it becomes victimized by it. By adopting the stance that the formation of aesthetic canons is beneath its more “scientific” interests, academic film study effectively clears the way for mainstream huckmeisters to carry out this work without interference or fear of contradiction. It thus becomes all the easier for an organization like the American Film Institute to join forces with the studios in carrying out work that universities should have attended to decades earlier — the subject of my next chapter.