From the March 22, 2002 Chicago Reader. I’ve seen a good many more Apichatpong Weerasethakul films since then, including many of his early shorts, and he continues to amaze me with his range, versatility, and poetics. — J.R.

Mysterious Object at Noon

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul

Written by Thai villagers

With Somsri Pinyopol, Duangjai Hiransri, To Hanudomlapr, Kannikar Narong, Kongkiert Komsiri, and Mee Madmoon.

In America the cultural objects we know consist mainly of things publicists know how to advertise, journalists know how to describe, and teachers know how to classify. This might not be so bad if publicists, journalists, teachers, and the organizations they work for didn’t have fairly rigid ideas about cultural objects — about where they come from and what we’re supposed to do with them. Movie entertainment, we’re told, is produced in this country and Hong Kong; movie art is more apt to be produced in Europe. So when Spanish director Alejandro Amenabar makes an arty thriller — such as the 1997 Open Your Eyes — it gets shown here in a few art houses; when his film is remade as an even artier, though not as good, Hollywood thriller — last year’s Vanilla Sky — it winds up in thousands of shopping malls. An earlier Amenabar thriller that’s much better than either Open Your Eyes or Vanilla Sky — a slasher movie set in a film school, Tesis — hardly gets shown here at all, presumably because the only kind of slasher movie our publicists, journalists, and teachers know how to process is the homegrown variety. It doesn’t matter how good a slasher movie is; if it isn’t American, the odds of us seeing it on a big screen are close to nil.

The odds are even worse if a movie — whether a slasher flick, an art movie, or an experimental film — is from a country such as Thailand. We never hear of Thai filmmakers, and the only roles we’ve been allowed to see Thai actors play are villains and hot babes in action-adventures set in Asia, James Bond pictures providing the prototype.

I don’t want to suggest that I know much about Thai cinema. But the two most memorable Thai filmmakers I’ve encountered — the radically different Pen-ek Ratanaruang and Apichatpong Weerasethakul — confound the stereotypes so thoroughly they make it clear that we Americans don’t know what Thai cinema is.

Ratanaruang was born in 1962, did an eight-year stint at New York’s Pratt Institute, and has worked as a freelance illustrator, designer, and art director. He’s a skilled commercial craftsman and witty satirist who’s been influenced by Alfred Hitchcock and Quentin Tarantino, among others, and his highly entertaining and inventive features Fun Bar Karaoke (1997) and 6ixtynin9 (1999) [see above] have reportedly cleaned up at home. (I haven’t heard how his 2001 TV series Transistor Love Story was received.) Weerasethakul was born in 1970 and is an architect, multimedia artist, and experimental filmmaker. His singular Mysterious Object at Noon (2000) — showing at the Film Center on Thursday, March 28; the filmmaker will be present — was financed largely by a Dutch state grant tied to the Rotterdam film festival, as well as by Toshiba and a James Nelson Award.

I attended the world premiere of this film at the Rotterdam festival two years ago, and I remember wondering how long it would take to reach Chicago — if it ever got here. The film made a strong impression on me, but I forgot many details, simply because I didn’t have an analytical context in which to place it. Perhaps if the film had been less original or striking, I and other publicists, journalists, and teachers could have started packaging it immediately.

It’s the only work of Weerasethakul’s I’ve seen — he’s credited with seven preceding shorts, all made during the 1990s — but it clearly offers more ideas than the entire oeuvres of other experimental filmmakers I could name. The difficulty we have processing experimental ideas in a Thai context fascinates me: how many of our ideas about experimental filmmaking are predicated on unthinking Western reflexes and traditions that exclude many small countries as a matter of course? The obstacles are ideological, conceptual, and even practical — for example, “Apichatpong Weerasethakul” isn’t an easy name for Westerners to pronounce or remember — and all sorts of anomalies are connected to the project that complicate our responses. For starters, the film is in black and white, which is now more expensive to use in the U.S. than color; this suggests that Thai filmmakers have more freedom than their American counterparts when deciding which to shoot in. It’s bemusing that this feature was shot on 16-millimeter and blown up to 35, yet the image we see is letterboxed, a format we Yanks are used to seeing only on video. The Dolby sound track is also unexpected.

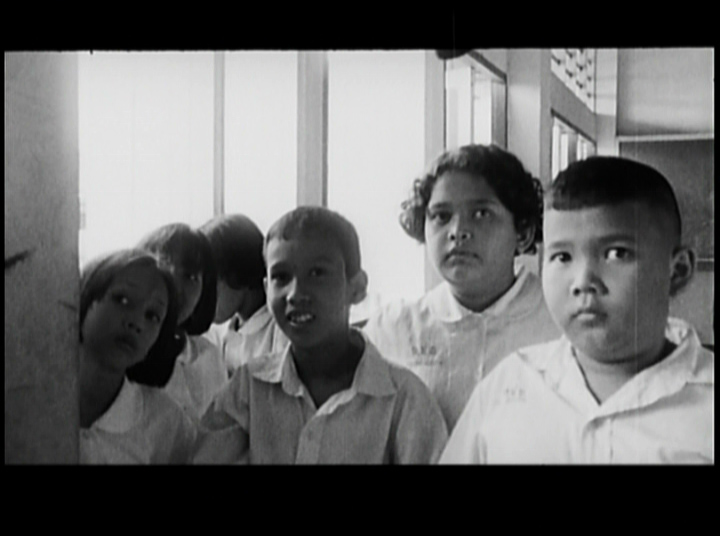

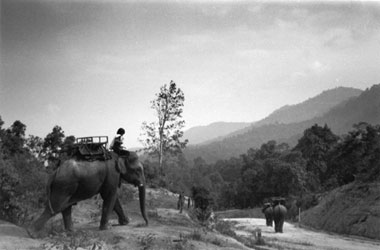

The film’s methodology and structure are even more startling. The film crew traveled through Thailand from north to south, inviting ordinary people to invent and then continue a story. New participants were free to alter the story they inherited, changing details and proposing alternative developments. Sometimes several participants at once pick up the story, as when a large group chants about various plot turns with musical accompaniment in front of a live audience and when competing narrative details are offered by schoolchildren near the end. Then the crew returned to Bangkok to shoot the fictional dramas and variations with nonprofessional actors and to film interviews with the actors as well as documentary segments chronicling the activities of both the actors and film crew. The final editing doesn’t homogenize these activities; rather it bears witness to all of them, cutting between stories being told and reenacted, overlapping the sound of one activity and the image of another, juxtaposing an intertitle and a filmed testimony, and including documentary segments about the stages of this adventure. The whole process took about three years.

Before we get to the invented story, we ride through the streets of a city, presumably Bangkok, while we hear both a man telling one story and an Asian pop song on the radio. After what sounds like a commercial for incense, we see a woman who helps run a fish stall tearfully recount her father’s efforts to sell her when she was a child to her uncle and aunt, which prompted her move to Bangkok. Weerasethakul asks if she wants to tell another story, real or fictional, and after cutting away to a few more narrative interludes, he gives us a simultaneous telling and enactment of the invented story, which involves a boy in a wheelchair who’s tutored at home in a Bangkok suburb.

At one point his teacher excuses herself from a lesson to go to the bathroom and doesn’t come back. The boy goes looking for her, finds her unconscious on the floor, tries to revive her, and sees a mysterious object roll out from under her skirt. In three of countless subsequent versions, the mysterious object becomes a flying ball that produces a miniature boy, the teacher becomes two teachers, and the teacher returns to the boy in the wheelchair as if nothing has happened, saying she just went off to buy him an eraser.

In a famous game of the Surrealists, “The Exquisite Corpse,” participants made up successive parts of a story, sentence by sentence, on a piece of paper with many folds, each participant reading only the previous sentence before adding another. The game of Mysterious Object at Noon — whose title obviously refers to the film as well as the object that rolls out from under the teacher’s skirt — is played somewhat differently, but it has the similar effect of revealing the collective unconscious of a group of unconnected storytellers. These people include, as the Rotterdam festival’s catalog puts it, “quarreling food sellers, a TV-addict-cum-boxer, a devout female cop and a loveless rubber-tree peeler”; we also encounter, among others, a herd of elephants and “a deaf neighbor who is introduced as a silent witness” — actually two deaf neighbors, teenage girls who use sign language to correct and amplify each other’s testimony. At the end, schoolchildren take over the entire show; the “noon” of the title apparently refers to a time when they play outdoors.

After a while the characters, fantasies, significations, and representations become so plentiful we may feel that Weerasethakul has bitten off more than he can possibly chew, even given a running time of 83 minutes. Apparently he wants to explore the collective unconscious of the participants for reasons that are both realist and surrealist — to reveal something real about Thai villagers through their fantasies and to reveal something about their fantasies through their reality. That’s only a beginning of course, but it’s a central part of the business of experimental films everywhere to provide us with beginnings of this kind and to invite us to run with them. The creative contributions of this film’s viewers are not unlike the responses of the Thai villagers. What is that mysterious object? Good question, and the answer’s partly up to us. Quick answers are encouraged — though not hasty packages of the results. Experimental films are frequently criticized for being boring because they say and do too little, but the best of them put us in exhilarating overdrive because they offer too much.