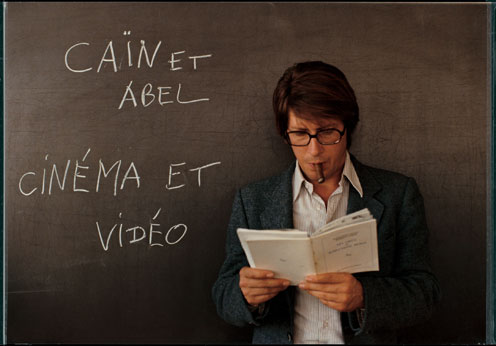

From The Soho News, September 24-30, 1980. Their title (not mine) was “Bringing Godard Back Home”. This is the first of two interviews that I’ve had with Godard to date; the other one, 16 years later, can be found here. — J.R.

Jean-Luc Godard seems to be into transportation metaphors a lot nowadays. It’s been rumored that when Paul Schrader sidled up to him recently at a film festival and said, “I think you should know that I took something of yours from The Married Woman and put it in American Gigolo,” the Master coolly replied, “What’s important isn’t what you take — it’s where you take it to.”

Every Man for Himself, Godard’s first movie to open in America and show at the New York Film Festival in eight years, is first of all a vehicle designed to bring him back to us. It has all the ingredients that mainstream critics have been clamoring for: stars (Isabelle Huppert, Jacques Dutronc), clearly defined characters and plot, lush music, beautiful 35mm photography, flaky eroticism, humor. “I’m really making my landing on the earth of story,” Godard tells me at one point. “Like a plane.”

Can it be sheer coincidence that he seems to take up prostitution as a theme only when he’s working in 35mm? After a prostitute in his new film (Huppert) turns a trick with a character named Paul Godard (Dutronc), she’s mauled by some thugs, told and forced to repeat that no one is independent. This makes me think of Godard’s own predicament as a filmmaker – including the fact that most of his 70s movies are still unreleased here (although the five-year-old Numéro deux will be surfacing in a few months). It’s the first thing I ask him about after we climb into the back of a limousine taking us through late-afternoon traffic, from a midtown screening room to LaGuardia Airport.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM: Does this parallel seem relevant to you?

JEAN-LUC GODARD: Yes, I think so. I didn’t think of that while working on the scene, but…independence is something you have to find inside yourself, too. Most filmmakers see themselves as independent, or art as independent. Finance people think they’re independent from art! (Laughs.) Art and economy are always related….Maybe I’m just approaching my real capacity to do a feature.

JR: I suppose that the previous film of yours that Every Man for Himself most reminds me of is 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her. But one thing that sharply distinguishes it from most of your earlier work is its rejection of Paris — the fact that it’s all set in your native Switzerland.

JLG: I was out of Paris 25 years ago, when I was writing for Cahiers du Cinéma. I remember a letter I wrote to my friends Truffaut and Rivette — around the time of the first Astruc film, when I was working on a dam. I remember complaining to them about their prejudice for the city movie. I’m not against cities — I’m against so big a city.

JR: Could you describe the programs that you’ve done for French TV?

JLG: About five years ago, there was a six-part series, About and Under Communication, 6 X 2. The first part of each program was an hour-long interview with someone in a steady [fixed] shot — a worker, mathematician, amateur filmmaker — and then another hour where we tried to do some research related to that. Than three years ago we did 12 half-hour programs, The Tour of France Told by Two Children, which were shown only last summer. In the middle of each was a 15-minute steady shot, speaking with a girl of eight and a boy of nine; the rest was introduction and commentary.

Right now I’m working on three projects together. I have a contract with the government of Mozambique to study television for them while they’re building it. They want comments about it — maybe a shot report, not with written words but with images. I’m doing A True Story of the Movies, which some Dutch people are financing, also a two-year project. Then I have a project in America with Zoetrope Studios, to make a script — but instead of writing it, shooting it. So when the executives ask, “Do you have a script?” I can say, “Yes,” and when they say, “May I read it?” I’ll say, “No — but you can see it.” We’ll have two masters, in video and 35mm. So if there’s no picture made after that, maybe we can show this on TV or sell it like a documentary. It’s called The Story. Why people need a story — it finally digs into that.

JR: Do you foresee making films with stories in order to make other films without stories?

JLG: I’m trying to mix the two together — to work for government, universities, or doctors. If it’s something done for the Mozambique government, maybe it can interest some UNESCO people or some other country – but obviously not Loews Theater. That was my problem: It took me almost 20 years to realize that films like Ici et ailleurs and Comment ça va shouldn’t be done for theaters but just for study, or for a certain category of people. And then it’s difficult, because sometimes these categories can’t afford the money. If you go the usual route, even the art-house route, you should have a proper way of doing it. If not, the resistance will be too strong. They’ll say, “This is not a movie.” Like the people in French TV who say, “This is not TV.” They don’t say it’s bad or worthless. The only censorship is aesthetic: “This is not the way a movie should be done.”

I live on the border. We’re Swiss people, we have a French company, and we want to keep it that way and live on the border. Our only enemies are the customs people, whether these are bankers or critics….People think of their bodies as territories. They think of their skin as the border, and that it’s no longer them once it’s outside the border. But a language is obviously made to cross borders. I’m someone whose real country is language, and whose territory is movies.

JR: There’s been a strong sense of your absence as a critic.

JLG: I want to go on with that, but with movies, not with pen and paper. Try to be a critic, not a regular reviewer. Sometimes I prefer teachers who do occasional pieces. It’s not possible to be a critic once a week.

JR: I find it impossible.

JLG: It is impossible. Even if you’re a genius, you can’t do it.

***

What else has Godard been doing lately? Giving lectures in Montreal on the history of film that have been transcribed and recently published in France. Producing the 300th issue of Cahiers du Cinéma, which contains letters to friends and acquaintances (“No one answered, not even friends – I don’t know why”), fragments of an interview, diverse collages of words and images.

Moving places. Interviewing Chantal Akerman for the magazine Ça. Inviting Jacques Tati to play a small part in Every Man for Himself. (He refused.) Inviting Marguerite Duras to play a small part. (She accepted, but insisted on remaining out of camera range, letting only her voice be heard.)

In short, trying to work with other people. (“I’m trying to do something with other directors whom I respect. I’m trying to learn my job, which I find impossible. It’s my problem, but I’m trying to say it’s our problem.”) trying to communicate: “If there was a true film magazine, it would help people to communicate the way that scientists do. That’s why science is so strong, whether it’s in the Pentagon or wherever. The Tokyo scientist is working with the San Francisco scientist; they send letters back and forth.”

***

JR: But today people seem less interested in films and more interested in filmmakers — the groupie syndrome.

JLG: Yes. But in France, that was mainly because we, the New Wave, said directors are so important. It was in order to have our right to exist as directors, because we weren’t authorized then. Now everyone thinks that directors are like God. Even if you say to a fellow director, “You’re better as a scriptwriter,” he feels puzzled, as though being a screenwriter is inferior. But I don’t think that. I think I’m not a very good screenwriter who can be a good director.

JR: Have you had any exposure to the Rocky Horror Picture Show cult?

JLG: No.

JR: It’s a teenage cult that sees this one movie hundreds of times, participating directly in a kind of ritual. What intrigues me is the way the audience uses the film as a means of communication — not the film itself communicating, but an audience communicating through a film.

JLG: It’s like certain images of traveling. Maybe I say that because I’ve been traveling a lot over the years. People like to think of themselves as stations or terminals, not as trains or planes between airports. I like to think of myself as an airplane, not an airport.

JR: So that people should use you to get certain places and then get off?

JLG: Yes. I’ll work much more on that in my next film. Maybe, if it has to be in a research picture, it’ll be a study, and I’ll take the best of that and use it in a real feature. Because it shouldn’t be put into a picture as I’ve done it here — I quite agree with that. There aren’t more changes of rhythm in the picture, that’s why they’re bad. Even silent pictures had tremendous changes of speed, and were never shown at the same speed they were shot. Today in any current picture the actors speak at the same speed that they speak on TV, where there is no risk. Images come just because of the spoken words: He has to say that, she has to say that, they have to say that. So they don’t look at what they’re shooting anymore, and they don’t listen to the sound. They just listen to the words and see if they correspond to the written words.

There’s much more story in a piece of music by John Coltrane or Patti Smith than in most films now. They lack a picture sometimes, but they’re doing a kind of screenwriting without a screen, without writing. And there’s much more than in regular movies. The way they work with sophisticated equipment -– I mean, maybe the camera, lab, and editing table are sophisticated, but in the in-between is so conservative!

The way they make records is much more bold than the way they shoot movies. They record at night when they feel like it. They do it in pieces, they do it again, they make changes –- they discover from listening what’s to be done. But in movies, the written script is obeyed like a law. It’s becoming stronger and stronger, because the pictures have changed into school now.

JR: How did you work with Gabriel Yared, the composer of the score for Every Man for Himself?

JLG: Unfortunately only after shooting, instead of at the same time or before. Next time — since I know him now, and the experience was new to me -– it’ll be done better. And I’m trying to put pictures on a year’s schedule, working from time to time rather than continuously. I’m trying to work with some of the actors who know me now, maybe once again with Isabelle and with musicians — so we can set up a session and then meet again, say, a month later. The aim is to build the music together. I mean, Patti Smith and her piano player are working together more closely than I work with my cinematographer.

***

I’m thinking of the emphasis on music in Every Man for Himself, an American Zoetrope release “composed” by Godard (as the credits indicate). By now, we’ve pulled up at Air Canada, and Godard invites me into the terminal to see him off on his plane for Toronto.

I ask him how he likes Poto and Cabengo, made by his erstwhile collaborator Jean-Pierre Gorin. Very much, he says, adding that he and Gorin had both been very nervous about whether he would or not. He was particularly struck by a use of stop-frames paralleling his own, which he said neither of them discussed in advance.

He gets to see fewer films than he likes because of his small-town base, halfway between Lausanne and Geneva. He likes two recent Andrzej Wajda films a great deal: Man of Marble and one about divorce whose title escapes him — with a final scene like Kramer vs. Kramer, he says with a grin, but done the way that a real director would do it.

We speak briefly about Tati’s Playtime (“It’s a good movie”), as well as Tati’s illness and bankruptcy. I ask Godard about the scene he wanted Tati to appear in. While Paul Godard stands in front of a cinema showing City Lights, a man steps out, protesting, “There’s no more sound here!”

JR: Why did you include that detail?

JLG: I don’t know. I don’t like what I call empty shots, that are there just for screenwriting reasons. I think the sound is always awful in theaters, and the projectionist’s job is awful because they aren’t paid well. And I worked very carefully on the sound in this movie. If there isn’t something in the shot, you have to bring it. I can’t imagine how a lot of moviemakers are doing shots just to explain something in the story. No painter would ever paint an image, no musicians would ever record a sound, for such a reason. I’ll never show someone crossing a street so you’ll understand he’s going from one place to another. I’ll do it if I like the street, or because of the light, or because of something. If not, I won’t do it, I’ll cut it.

— The Soho News, September 24-30, 1980