From The Independent: Film and Video Monthly, November 1985 — J.R.

Having attended festivals of many shapes and sizes around the world, I can think of none that is more conducive to the serious viewing of original, offbeat work than the Rotterdam Film Festival. While Rotterdam lacks the global media coverage and accompanying hoopla of a Cannes, Toronto, Venice, Filmex, or Berlin, the festival offers filmmakers a congenial and sympathetic setting. Significantly, American independents as diverse as Jim Jarmusch and Mark Rappaport — as well as European figures like Manoel de Oliveira and Raul Ruiz — made their mark there long before they were treated to New York Film Festival premieres.

A cash prize is awarded each year to a film selected by the Dutch critics. Most recently, it went to Ruiz’s Manoel à l’ïle des merveilles (see two stills above), a French-Portuguese television co-production shot in 16mm, comprising three 50-minute episodes. However, the overall spirit of the festival is anything but competitive, and as a rule the critics prize will go to a film that the critics feel is deserving of special attention rather than an audience favorite. In 1984, the prize went to U.S. avant-garde filmmaker Peter Hutton for a series of short nonnarrative films that had not been widely attended. Ruiz’s Manoel, shown only in Portuguese with simultaneous voiceover translation, was not seen by the majority of the festival-goers either.

Evening galas are presented nightly at the Luxor, a large and rather plush commercial theater located across the street from the Rotterdam Hilton. All other films in the festival proper are shown about a quarter of a mile away at the Lantaren, a four-story containing the festival offices, a good-sized restaurant and cafe, a room for viewing videotapes, and no less than half a dozen screening rooms — most of which are in continuous operation from 9 a.m. until well after midnight. Most films are repeated several times, although there are often last-minute changes in the schedule and program on a day-to-day basis. Some of these are reflected in the festival newspaper, which appears daily in both Dutch and English, and usually functions as an indispensable guide to what has just happened or is about to happen.

While everyone on the affable festival staff speaks English, the spur-of-the-moment reschedulings can create confusion. Last year. for instance, I was incorrectly billed as the director of Leslie Thornton’s Adynata (see above) at the screenings I arranged for her film at the last minute. Although these occasional glitches do appear, they are nearly always quickly remedied, thanks to the festival’s good will and intimacy.

In 1984, the festival inaugurated an international Film and TV market at the Hilton. Apart from being the hotel where a good many of the festival guests stay, the Hilton also houses other festival activities, most notably the nightly interviews with directors, stars, and other figures accompanying the Luxor premieres in a relaxed nightclub setting.

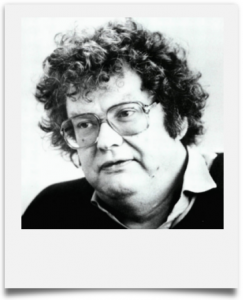

Both the eclecticism and the energy of the Rotterdam Festival are in large part the personal expression of Hubert Bals, the festival’s director. Bals’ unpredictable yet distinctive taste rules all the selections (aside from those available on the Market), and his relaxed intensity leads to an atmosphere that resembles, in the words of filmmaker Jackie Raynal, “the Telluride of Europe”. As a result, Rotterdam attracts a rare mix of filmmakers. Charles Burnett, Alex Cox, Robert Downey, Philippe Garrel, Henry Jaglom, Joseph Mankiewicz, Eric Rohmer, John Sayles, and Andrei Tarkovsky are among those who have attended in recent years.

Rotterdam is also flexible about screening films and tapes of a variety of running times. They range from extended television series to hour-long featurettes, oddball shorts, and documentaries of varying lengths. This year’s nonfeature lineup included the German TV series Heimat; Chantal Akerman’s L’Homme à la valise [see above still]; Elizabeth Lennard’s Tokyo Melody, a portrait of Japanese composer and pop star Ryuichi Sakamoto; Mark Peploe’s 35m half-hour adaptation of a D.H. Lawrence story, Samson and Delilah; three films about labor unions by Chicago’s Kartemquin Collective; and Amnon Buchbinder’s Criminal Language and Oroboros, both theoretical, narrative avant-garde films. All these films, which might easily have been overlooked or ignored at larger festivals, found audiences in Rotterdam. Working on the principle of target audiences, Rotterdam proves that less can be more under the right conditions.