From the Chicago Reader (November 24, 1995). — J.R.

Eyes Without a Face

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Georges Franju

Written by Jean Redon, Pierre Boileau, Thomas Narcejac, Claude Sautet, Pierre Gascar, and Franju

With Edith Scob, Pierre Brasseur, Alida Valli, Juliette Mayniel, Béatrice Altariba, François Guerin, Alexandre Rignault, and Claude Brasseur.

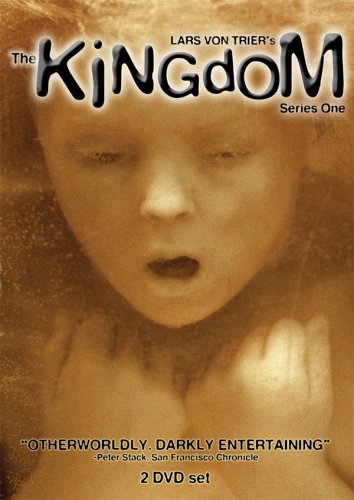

The Kingdom

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Lars von Trier and Morten Arnfred

Written by von Trier, Niels Vorsel, and Tomas Gislason

With Ernst Hugo Jaregard, Kirsten Rolffes, Ghita Norby, Soren Pilmark, Holger Juul Hansen, Annevig Schelde Ebbe, Jens Okking, Otto Brandenburg, Baard Owe, and Birgitte Raabjerg.

They’re both arty European fantasy meditations on the medical profession — that’s about all that Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (1959) and Lars von Trier’s The Kingdom (1993) have in common, apart from the fact that they’re both opening here the day after Thanksgiving. The differences between them are much more instructive. Franju’s Les yeux sans visage is a poetic, compact (88 minutes) black-and-white French horror picture about skin grafting that premiered inauspiciously in the United States 32 years ago in a dubbed and reportedly mangled version known as The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus; happily, Facets Multimedia is showing it in its original form and subtitled. The Kingdom is a four-part, 279-minute miniseries made for Scandinavian television on color video and transferred to film, and it might be described as a supernatural Danish soap opera with allegorical overtones and offbeat inflections — a sort of Danish Twin Peaks. The Music Box is offering viewers the option of seeing it all at once or on two separate dates for the same ticket price.

Though it didn’t exactly bore me, I must confess that The Kingdom was a disappointment after what I’d been hearing from friends in New York. For all the thematic ambitions of von Trier’s 1991 Zentropa, what impressed me about it was its fancy technique and visual style; after all, this feature was shot mainly in black and white by Henning Bendtsen, the same man who shot Carl Dreyer’s Ordet and Gertrud. These virtues pretty much go out the window in The Kingdom, where the primitive colors (most of which seem to be citrus-tinted) and the rough, pixel-laden textures sometimes make it look as if the movie were being projected on burlap. Early in the third episode, in a sequence involving a lit candle and a face in close-up, this texture improves substantially — making me wonder whether von Trier or his codirector, Morten Arnfred, might have shot a few bits on film or found a better lab for video-to-film transfers. But before long it goes back to the same old mottled video textures again.

No less annoying is the crude miniseries structuring — mechanical crosscutting between one set of characters and another, guaranteeing that we never stay with any single story line for long. This as well as the visual crudeness might have irritated me less if I were watching it on TV, where such simplicities are routinely tolerated in exchange for the comforts of being at home. We’re living through a transitional period when it comes to film and video. Reviewers are often expected to ignore the differences between the media while both filmmakers and video artists are obliged to present their work in a transferred state: video artists usually have to transfer their work to film if they want it to be shown at film festivals, and many independent film artists who can’t afford to set up preview screenings for reviewers find themselves settling for “preview tapes” instead.

On the other hand, the handheld-camera movements and deliberately ragged and unconventional cutting of The Kingdom give the work a documentary feel that meshes interestingly with the outlandish material: the story involves ghosts, stolen body parts, mental telepathy, a secret society of doctors (known as “Sons of the Kingdom”), conspiracies, voodoo research (which takes one leading character to Haiti), and old medical reports buried in archives. For this is a miniseries about what might be described as a palace intrigue, medieval in flavor even though it’s set in a contemporary hospital. Indeed, the best of The Kingdom may remind us more of the literary fantasy of Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy than of Paddy Chayefsky’s The Hospital. The downside of this resemblance is that Peake’s vision would call for a big-screen movie, not a video transfer like The Kingdom. (And Chayefsky’s pinched and bloated vision is TV to the core, whether or not it’s on a big screen.)

I’m not sure how much The Kingdom has to say about Scandinavia in general and Denmark in particular, but there seems little doubt that von Trier wants it to say a lot. Unfortunately, the hospital-as-nation metaphor seems almost as unwieldy and pretentious here as it was in Lindsay Anderson’s top-heavy satire Britannia Hospital (1982), and periodic aerial shots over an enormous building that’s supposed to be “the Kingdom” (i.e., the hospital) are more rhetorical than convincing. Arguably The Kingdom works better as a weirdo cult item than as the grandstanding state-of-the-union address it sometimes pretends to be. For instance, the anti-Danish gibes of Stig Helmer (Ernst Hugo Jaregard), a petulant Swedish doctor, made more sense to me as an eccentric character trait à la Twin Peaks than as a telling illustration of Scandinavian rivalries. (The film is coproduced, incidentally, by Danish, Swedish, and “Nordic” television.)

A couple of years ago, during my only trip to Scandinavia, I was giving a lecture about American cult films at the annual convention of the Norwegian federation of film societies when someone suggested I put on a video of a suppressed Norwegian TV kids show of the 70s as an example of a much-discussed local cult item. This black-and-white slapstick piece about a couple of house painters didn’t have much coherent dialogue (which made it pretty easy for me to follow), but it did have a fair amount of nastiness and malevolence. It had been taken off the air for fear of upsetting children, and many of the film-society directors present, who were kids at the time, grew to cherish it over the years precisely because it was unavailable. A similar cult infatuation with Twin Peaks has developed since the TV show and subsequent feature flopped with the mass audience, manifesting itself in such efforts as a hardy ‘zine called Wrapped in Plastic.

One wonders if The Kingdom may be undergoing such a transformation in Scandinavia. According to an article about von Trier in the November-December issue of Film Comment, the series is “still in progress,” though the film’s press book doesn’t allude to any more episodes in production or preproduction. (Von Trier’s Dimension, on the other hand, has a projected production schedule that runs from 1991 to 2024, and his Breaking the Waves is said to be in preproduction.) Though the first four episodes of The Kingdom build to an elaborately crosscut and partially satisfying string of climaxes, one can’t be sure whether the story has truly ended or not; perhaps von Trier doesn’t know himself.

***

Although he was the cofounder (with Henri Langlois) of the French Cinémathèque, Georges Franju (1912-1987) is not nearly as well known nowadays as Lars von Trier — which shows how little reputations today have to do with actual achievement and how much they have to do with recent commerce. Admittedly Franju’s nine features — apart from Eyes Without a Face and his 1963 Judex, a tribute to the great silent director Louis Feuillade — have seldom been shown in this country. And it could be argued that he never surpassed his early documentary shorts, like the 1949 Blood of the Beasts (an honest, profound, lyrical, and deeply shocking look at everyday work in a Paris slaughterhouse), the 1951 Hôtel des Invalides (a macabre vision of a war museum and the mutilated World War I veterans who piously visit it), and the 1952 Le grand Méliès (a biopic about the great magician and film pioneer).

Yet this anticlerical, morally committed film artist must be a central reference point whenever we talk about the transgressive poetry of shock. Franju had strong ties to the French surrealists, to Jean Cocteau (who said in praise of Eyes Without a Face, “The more you touch on mystery, the more important it is to be realistic”), and to German fantasy directors like Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau. “Hammer Films meets Georges Bataille” was English critic and filmmaker Christopher Petit’s elegant formula for Eyes Without a Face. And if there’s any black-and-white movie in town this week that demonstrates the awesome difference between 35-millimeter film and video, it’s this one — filmed by German-born cinematographer Eugene Shuftan, who won an Oscar for The Hustler only two years later. For chilling noirish textures, check out the remarkable opening sequence (“as haunting as the first dream of a dead man,” wrote novelist Iain Sinclair), which shows Alida Valli driving a black Citroen DS at night down a tree-lined road to a river to dispose of a female corpse wrapped in a raincoat.

The plot is as absurd, naive, and obsessive as a fairy tale. Professor Genessier (Pierre Brasseur) is a celebrated plastic surgeon whose reckless driving caused the facial disfigurement of his beautiful daughter Christiane (Edith Scob). Encouraging the police to believe she’s dead, the doctor compels her to wear a molded mask and to live in seclusion until he’s able to furnish her with a substitute face. Genessier’s devoted assistant Louise (Valli), the beneficiary of an earlier skin graft, hunts out beautiful young women with faces like Christiane’s around the Sorbonne and lures them back to the professor’s chateau, where each in turn is drugged and her facial skin cut away. But each time the operation is a failure.

This basic plot is embellished with such baroque elements as the professor’s dog kennels (heard more often than seen in the film’s creepily creative sound track) and the doves he keeps locked up; both dogs and doves figure centrally in the final sequence. Other memorable details include Maurice Jarre’s icy, mocking, jaunty score, the elegant Givenchy gowns worn by the women, and Christiane’s eerie molded mask, which makes her look like a department-store dummy.

Many critics have described the film as an attack on modern science, but the sense of moral outrage can perhaps be attached more specifically to the practice of plastic surgery, which back in the 50s seemed as obscene to some people — check out Charlie Chaplin’s treatment of it two years earlier in A King in New York — as organ transplants would about a decade later. One of the central sequences in Eyes Without a Face shows a face-lift operation (actually expertly faked) in clinical detail. And though this sequence may be slightly less shocking today than it was in the 60s, when the film played briefly in the U.S., it still “takes us implacably to the end of what our nerves can bear,” as Cocteau noted. The same could be said for the animal slaughter in Blood of the Beasts, where the ethical confrontation with taboo material combined with what critic Noël Burch has called “an almost musical interaction between moments of tension and moments of respite” also creates a potent mixture.

Indeed, thanks to the relative puritanism of U.S. culture, the formal treatment of cruelty — as evidenced in such writers as Sade, Lautréamont, and Bataille — seems to us specifically French and surrealist, even though Anglo-American thrillers and horror movies often play with much cruder versions of these writers’ transgressions. Ironically, it’s Franju’s delicacy that distinguishes his work so radically from later splatter-and-slash movies. Psycho and Peeping Tom, we should recall, were released a year after Eyes Without a Face opened in France, though they were shown two or three years before Franju’s film opened here. I can still remember arguing circa 1963 with a friend in Alabama about The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus, which he regarded as trash and I maintained was art. (Most English and American viewers did dismiss the film as trash back then, but they were certainly shaken by seeing it; in his interview with Francois Truffaut in Cahiers du Cinema, Franju reported that when Les yeux sans visage was presented at the Edinburgh film festival seven people fainted, and the public and press were both offended.)

Up to this point I’ve linked Franju’s poetry to certain French art traditions, yet it seems to me that there’s a historical fact implicitly standing behind this movie: the German occupation of France, and all the baggage that goes with it — among other things, the Nazi medical experiments on Jews and others; the attack dogs they kept, like Genessier’s kennel dogs; and even certain film traditions associated with Germany. To quote Cocteau yet again on Eyes Without a Face: “The ancestors of this film live in the Germany of the great cinematographic epoch of Nosferatu.”

Robert Bresson’s acute sense of form — including his special feeling for offscreen sounds, which Franju appears to have learned from — could be tied directly to his experience of the occupation and the resistance, as could his feeling for hidden identities and buried emotions. Franju’s frozen poetry may be connected with the same dark era. Von Trier — who was born in 1958 — is distant from that period, however, so when he depicts it in Zentropa the work has a certain hollowness, which The Kingdom occasionally echoes. By contrast Eyes Without a Face, for all its intermittent camp and occasional absurdity, conveys the conviction of an artist who’s tasted the horror of the 20th century and has something to tell us about its flavor.