Conversations conducted for Movie Mutations and Abbas Kiarostami (both 2003). — J.R.

Open Spaces in Iran and Africa:

Conversations with Abbas Kiarostami

by Jonathan Rosenbaum and Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa

1. Taste of Cherry: spring 1998 (Chicago)

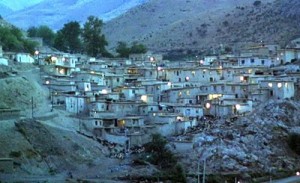

The hero of Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry is a 50ish man named Mr. Badii contemplating suicide for unstated reasons, driving around the hilly Tehran outskirts in search of someone who will bury him if he succeeds — he plans to swallow sleeping pills — and retrieve him from the hole in the ground he has selected if he fails. Over the course of one afternoon, he picks up three passengers and asks each of them to perform this task in exchange for money — a young Kurdish soldier stationed nearby, an Afghan seminarian who is somewhat older, and a Turkish taxidermist who is older than he is. The soldier runs away in fright, the seminarian tries to persuade him not to kill himself, and the taxidermist, who also tries to change his mind, reluctantly agrees, needing the money to help take care of his sick child. The terrain Badii’s Range Rover traverses repeatedly, in circular fashion, is mainly parched, dusty, and spotted with ugly construction sites and noisy bulldozers, though the site he’s selected for his burial is relatively quiet, pristine, and uninhabited. It’s arranged that the taxidermist will come to the designated hillside at dawn, call Badii’s name twice, toss a couple of stones into the hole to make sure Badii isn’t sleeping, and then, if there’s no response, shovel dirt over his body, and collect the money left for him in Badii’s parked car.

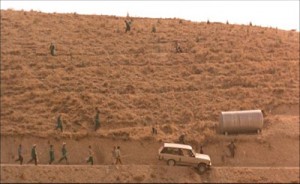

Later that night, Badii emerges from his apartment, proceeds in the dark to the appointed spot, and lies down in the hole, where we hear the sounds of thunder, rain, and the cries of stray dogs. The screen goes completely black. Then, in an epilogue, we see Kiarostami at the same location, in full daylight, with his camera and sound crew filming soldiers jogging and chanting in the valley below. Homayoun Ershadi, the actor who played Badii, lights and hands Kiarostami a cigarette just before Kiarostami announces that the take is over and they’re ready for a sound take. The shot lingers over wind in the trees, which are now in full bloom, and the soldiers and filmmakers lounging on the hill-side between takes, before the camera pans away to a car driving off into the distance. To the strains of Louis Armstrong playing an instrumental version of “St. James Infirmary,” the final credits come on.

***

Fax sent by Jonathan Rosenbaum to Abbas Kiarostami, November 18, 1997:

“Dear Abbas (if I may),

“I’ve been moved to write you this letter because of the distressing news I recently heard that you decided to delete the final sequence of The Taste of Cherry [sic] from the version of the film opening in Italy. I’ve also heard that there is a danger that you may cut the same sequence when the film opens in the United States. I must confess that when I heard this news, I experienced a painful feeling of loss — as if something I loved had suddenly been taken away from me. And I would like to try to persuade you not to touch a frame of your masterpiece.

“I’ve seen The Taste of Cherry three times — twice in Cannes [in May 1997] and once in New York [in October 1997] — and although I consider it to be one of your finest works, with or without the video ending, I believe that only with the ending as it now stands does it possibly qualify as your greatest film. I won’t attempt to explain all the reasons why I feel this way in a letter — although I will attempt to do so when the film comes to Chicago and I write about it in my newspaper. For now, I can only stress that I regard the ending as a very special gift to the audience — a gift that has complex and profound consequences in terms of how every viewer comes to terms with everything in the film preceding that ending. Without it in any way diminishing the remainder of the film, it allows it to reverberate in a wider, freer world, and allows the viewer to receive it in a fuller way. I should add that I don’t think this opinion is merely an `American’ or `western’ interpretation; [Iranian, Chicago-based teacher, writer, and filmmaker] Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, for example, fully agrees with me about the absolutely vital importance of the video ending. (I just spoke to her on the phone, and she asked me to tell you that she feels as passionately about this matter as I do.)

“I realize that The Taste of Cherry is a deeply personal work for you, and I wouldn’t presume to guess the reasons why the video ending troubles you. But I do believe that many of the greatest artists are capable of producing work that `understands’ more than the artists sometimes do as individuals; that, I assume, is why Gogol destroyed the second half of his Dead Souls after writing it — because his novel in some mysterious fashion knew more than he did. Not knowing you, it would be foolish for me to speculate why you’ve had second thoughts about the ending of The Taste of Cherry. But I do feel that I know something about your work, and the wisdom it imparts to me is something I continue to listen to. I humbly ask you to listen to the same wisdom, and to allow it to speak to others.

“Sincerely (and hopefully),

“Jonathan Rosenbaum”

Fax sent by Abbas Kiarostami to Jonathan Rosenbaum, November 20, 1997:

“Dear Jonathan (if I may)

“I just returned from a long trip and got your fax. I do appreciate your concern and also your feeling on cinema and I…

“As for the ending sequence, you are quite right and I have to say that I am not supposed to cut or change it at all, neither in my country or anywhere else. I just saw the dubbed version of my film in Italy and decided to play around the screening of the film with and without the video ending in several cities. Some theaters are showing the film with the video ending and some without. It’s just a sort of playing, done out of the film…a play that you can see the audience reactions after two different endings… frankly speaking, I like this play…it’s very interesting like cinema…

“Life does worth to experience anything once. If I could ever find a chance to meet you, I’ll tell you more in this respect.

“Then, assure you again, the ending will be the same.

“Thank you for your attention.

“Sincerely,

“Abbas Kiarostami

with regards to Mehrnaz.”

A few words about the preceding: my letter wasn’t prompted by any thoughts of publication, but simply by my alarm upon hearing, first, that many critics (Iranian as well as American) were trying to convince Kiarostami to delete his original ending from Taste of Cherry (which was still sometimes being called The Taste of Cherry at its festival showings), and second, that Kiarostami had done just that in Italy — which implied to me that he might do the same thing when the film opened in the U.S. It struck me as extraordinary that reviewers who see a film only once or twice could wind up as the final arbiters of works that filmmakers spent years working on, yet the recent and injurious recutting of other films prompted by reviews in trade magazines demonstrated that this practice was in fact on the rise.

It’s worth adding that Italian screenings of the film without the ending proved to be more popular than screenings with the ending, and after Kiarostami left Italy, despite his wishes to have the film shown in both versions, the distributor opted to show only the cut version. (To the best of my knowledge, this shorter version hasn’t been shown anywhere else in the world, but it’s difficult to be sure about this.)

Prior to our exchange of faxed letters, my acquaintance with Kiarostami was limited. Saeed-Vafa had introduced us and served as interpreter during a brief conversation at the 1992 Toronto Film Festival, and subsequently we had merely nodded at one another at two or three other festivals, then conversed again briefly — with Mehrnaz again serving as interpreter — at the 1997 New York Film Festival in October. (Mehrnaz and I had worked together, along with a few others, on the English subtitles of Forugh Farrokhzad’s only film, the 1962 short The House is Black, which showed with Taste of Cherry at the festival.)

On February 28, 1998, Kiarostami presented two prerelease screenings of Taste of Cherry at the Chicago Art Institute’s Film Center. In between those screenings, when I attended a dinner for Kiarostami, he asked me if my letter to him could be translated and printed in an Iranian film magazine, and I agreed, suggesting that perhaps his letter could be translated and printed as well. I later heard that my letter — though not his — appeared in Persian in Film International, and I’ve taken the liberty of reproducing Kiarostami’s letter here verbatim because I believe that what it manages to communicate is far more important than his grasp of English grammar (which is certainly far superior to my nearly nonexistent knowledge of Farsi). The fact that we were able to communicate at all in this fashion is fundamental to my sense of what this book is about — in particular the sense of mutual empowerment that can arise from such exchanges.

On March 1, the morning after Kiarostami presented Taste of Cherry at the Film Center, I arranged to meet him and Mehrnaz for a conversation over breakfast recorded specifically for Movie Mutations; Muhammed Pakshir, another Iranian living in Chicago, graciously drove us to the restaurant and joined us in part of the talk. Although it was mainly my intention at the time to discuss general issues about nationality and audiences, Kiarostami wound up explaining a great deal about his working methods — more than I had encountered in other interviews with him that I’d read at the time — and I’ve decided to retain portions of that material here.

Two subsequent interviews that Mehrnaz and I conducted with Kiarostami about his next two features for a book about him that we were cowriting are excerpted below to update some of his thoughts about interactive cinema, sound, nationality, and related matters. (Some parts of this material, I should add, don’t appear in the aforementioned book.) Our hopes of interviewing him yet again about his latest feature, 10 (2002), which we managed to see just in time to add something to our book, were ultimately dashed by the increased difficulties imposed by U.S. customs on Iranians entering the U.S. after 11 September 2001 — which even went beyond those described in ‘Squaring The Circle’ elsewhere in Movie Mutations — understandably convinced Kiarostami to cancel a planned visit in the spring.

MEHRNAZ SAEED-VAFA: Jonathan is preparing a book, and part of it will be this conversation with you.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM: Its working title is Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinema. “Mutation” implies biological transformation, and the basic idea is that there are changes going on all over the world in communications, technology, and economics that are changing the ways we think and write about cinema. We want to have sections in the book about Iranian and Taiwanese cinema, and when Edward Yang was in town a few months ago we already began discussing some of the issues I want to bring up here. For me, part of what links Taiwanese cinema to Iranian cinema is a certain resistance to western values.

ABBAS KIAROSTAMI: Why Edward Yang and not Hou Hsiao-hsien, whose style is more distinctive?

JR: Because he was here. Of course I’d also like to include Hou in our discussion as well.

MS: Jonathan wants to emphasize how audiences are hungry for an alternative — for a different vision.

JR: And it’s an interesting paradox that you’re perceived in most of the world as an Iranian filmmaker, whereas in Iran you’re perceived largely as a western filmmaker. How do you feel about this? What are the differences between the perceptions of your films in Iran and how they’re perceived elsewhere? I was very much struck by something a Peruvian film critic said to me in Chicago about a year ago: he had recently seen Hou’s Goodbye South, Goodbye, and he felt it had more to say to him about what’s happening in Peru now than any other film made anywhere else.

AK: I feel the same way — that our language, Hou’s and mine, is a universal language. And if film doesn’t cross geographical borders, what else can? Everything else serves to preserve the borders and separations of cultures, customs, and nationalities. Film is the only way of looking down at cultures from a less earthbound perspective.

JR: Yes, but whenever one crosses a border, the idea of nationality appears. Perhaps economic matters are more important than national issues — which is why the Peruvian critic was affected by Hou’s film: because people tearing down buildings and other manifestations of capitalism mattered more to him than the national differences between Taiwan and Peru.

AK: I also believe that Taiwan and Iran have many things in common — extraordinary similarities. And the most important of these are economic. Naturally, Iran is related to other countries through its economic situation, which is related to the political situation, and the political situation reflects the social situation. So all the countries with economic similarities have similar problems, which drives them to arrive at a common language.

I had a friend in Iran who was supposed to make a film in the United States, and he was afraid that if he was given a big budget, he wouldn’t know how to spend the money and couldn’t make a film according to his own standards. On the other hand, in Iran we sometimes don’t have enough money to make films. This kind of difference is the major disagreement between the cinemas of Iran and the United States. For example, if they invited me to make a film here and assigned me a big budget and a large crew, I’d have a lot of trouble making my own kind of film in those conditions.

JR: Raúl Ruiz hated making The Golden Boat in New York, because so many film students wanted to work with him as assistants and his crew became so large. But part of how that system operates in the U.S. is through unions. Are there unions of the same kind in Iran?

AK: Yes, in every part of the profession, but they don’t enforce their regulations so much, so you can still have a crew of less than ten people.

I think this changing taste in cinema all over the world partly stems from economic factors, but there are other important factors as well. One of the most important is a participating audience that is active, not passive. The filmmakers themselves aren’t the only spokespeople; spectators also have the role and the right to create part of the film. Just because they don’t have access to the negative and the film equipment doesn’t mean that they don’t deserve to be regarded as part of the film. I believe the present distance between the filmmaker and the audience is immense, and my kind of filmmaking is interested in reducing that distance. There are definitely people in the audience who are every bit as talented as I am or even more, and they should be given the opportunity to be creative and become part of the filmmaking.

It seems to me like there is only one audience everywhere I go, and I’ve learned a great deal from this significant similarity of audiences. I feel like I’m always in the same situation with the audience, and that there’s a similarity to their reactions, despite differences in nationality, religion, origin, culture, and language. For instance, when I was showing Through the Olive Trees in Taipei, I completely forgot that the audience there wasn’t Iranian. I had a similar experience in Rotterdam with Homework, an even more local film. I thought at first this was because there were some Iranians in the audience, but when the lights came on I discovered there weren’t any. I think all people are impressed by film in similar ways.

MUHAMMED PAKSHIR: I think what he’s trying to accomplish is the elimination of the separation between one filmmaker and thousands of spectators, and that’s a big achievement.

JR: Yes, and part of the way you’re achieving this in Taste of Cherry is by being multicultural. Someone pointed out at the Film Center last night that the three major characters apart from the hero are Afghan, Kurdish, and Turkish, and as you pointed out, that’s because Iran itself is multicultural. This is already a step in the direction you’re talking about, because what we’re calling “Iran” is in fact many cultures, not one — just as “America” is.

AK: And none of these cultural differences interferes with the film being understood. Spectators check their cultural baggage at the door, before they enter the theater; this is the way that audiences are similar.

***

JR: It seems that part of what makes your films so interactive is the fact that there are almost always missing parts of the narrative — absences that the audiences have to fill in some way.

AK: My ideal film is something like a crossword puzzle with empty squares that the audiences can fill in. Some people describe films as flawless, without cracks, but for me that means that an audience can’t get inside them.

MS: Did you inform the actors in Taste of Cherry when you were shooting and when you were just rehearsing?

AK: No. There was no film crew there. They would set up the camera for me in the car, because I was the only one around apart from the actor [i.e., serving as the stand-in for the character the actor was speaking or listening to].

JR: Did the actors have to memorize their lines?

AK: Nothing was written, it was all spontaneous. I would control certain parts and get them to say certain lines, but it was basically improvisation.

JR: So were all these actors speaking as themselves?

AK: Not exactly. The actor playing the soldier wasn’t a soldier; I prompted him beforehand about the location of the army camp, for example. It was a combination of real and unreal. For instance, I ordered some guns, so he thought he’d get a chance to shoot one of them later on, when we were filming, and he didn’t realize that this kind of instruction was the actual filming. He was even getting anxious and asking when the filming would start. I actually made him believe I was planning to kill myself.

It reminds me of a verse from the poet Rumi: You are like the ball I hit, so you are running, but I am also running after you.

JR: It seems to have something in common with jazz. Maybe that’s why I like your use of Louis Armstrong playing “St. James Infirmary” in the final sequence.

AK: Exactly. Because even though you’re following certain notes, you’re also following the feeling of the piece, so the performance you’re giving tonight will be different from the performance tomorrow.

JR: It’s also about playing together.

AK: Yes, but these actors can’t have a dialogue with each other because one part is always played by me.

JR: Right — you’re the composer and the bandleader.

AK: At one point, I wanted the soldier character to express amazement, but since I couldn’t ask him to do that, I started to speak to him in Czech. He said he couldn’t understand what I was talking about, and I used that in the film. At another point, I placed a gun in the glove compartment, and asked him to open it for a chocolate, when I wanted him to look afraid.

JR: One thing that Taste of Cherry conveys very powerfully is the experience of being alone, and your method of shooting intensifies that sense of isolation.

AK: There are signs in the film that sometimes made me think that the man didn’t really want to kill himself, that he was looking for a kind of communication with the other characters. Maybe that’s one of the ruses of his loneliness, to engage people with his own emotional issues. He doesn’t pick up a couple of workers at the beginning who would be willing to kill him with their spades; he chooses other people whom he probably thinks he can have a conversation with. So that gives us a signal that he’s probably not searching for someone who would help him to kill himself.

JR: It’s also interesting how your images metaphorically reproduce the situation of the spectator watching the film. In many of your films, the view through a car’s windshield represents that situation — of looking for something but also feeling separate from what you’re looking at.

AK: That comes from my experience of driving around Tehran in my car and sometimes driving outside the city — looking through the front, rear, and side windows, which become my frames.

2. The Wind Will Carry Us: spring 2000 (San Francisco)

JR: I’m curious about a particular moment in The Wind Will Carry Us, when the hero asks the little boy, “Do you think I’m a bad man?” and the little boy blushes and says, “No, I don’t think you’re a bad man.” When I saw that, I had the impression that it was you who asking the boy precisely that question. Is that correct?

AK: Yes, I was behind the camera and I asked him that question.

JR: It does seem very much like a personal response from the boy that isn’t an actor’s response, and for me it was a very important moment.

AK: I had to ask him that question because he didn’t like me very much — in contrast to the actor who was playing the main character. So that’s why he wasn’t very convincing when he called me a good man! (Laughter.)

JR: Yes, he was blushing and very fidgety. So were there only some scenes with the boy where you used this technique, or did you always use it?

AK: I always used it, except for when you see two people speaking in the same shot or when the person is on the telephone. When he’s on the phone, the method is always that I speak first and the character repeats what I say. And the time he has to wait for the answers to his questions allows him to listen to what I’m saying and just repeat it.

JR: Were you yourself carrying a mobile phone while you were shooting the film?

AK: It wouldn’t have even worked there — it was too remote. In order for a real mobile to have worked, you would have had to climb the equivalent of two mountains.

JR: There’s a parable by Plato about a cave that sees the shadows on the wall of a cave as a representation of reality. It can be read as a kind of metaphor about cinema, and the film’s only interior scene reminds me very much of that metaphor.

AK: My intention in this film and in my previous films is to show signs of reality that viewers won’t necessarily comprehend but will none the less feel. Basically anything seen through a camera limits the view of a spectator to what’s visible through the lens, which is always much less than we can see with our own eyes. No matter how wide we make the screen, it still doesn’t compare to what our eyes can see of life. And the only way out of this dilemma is sound. If you show the viewer it’s like peeking through a keyhole, that it’s just a limited view of a scene, then the viewer can imagine it, imagine what’s beyond the reach of his eyes. And viewers do have creative minds. If, for example, we don’t see anything but hear the sound of a car suddenly screeching to a halt and then hitting something, we automatically have a picture of the accident in our mind’s eye. The viewer always has this curiosity to imagine what’s outside the field of vision; it’s used all the time in everyday life. But when people come to a theater they’ve been trained to stop being curious and imaginative and simply take what’s given to them. That’s what I’m trying to change.

JR: I wonder if this is a key to what’s different in your sound conception for The Wind Will Carry Us. It seems like the field of what we hear is much larger than the field of what we see, and that the discrepancy between the two is much larger than in your previous films. Is that true? Is the canvas of what one hears much larger?

AK: The sound is supposed to assume the role of what isn’t visible. Throughout this movie it was a challenge to see if we could show without showing, to show what’s invisible, and to show it in the minds of the viewers rather than on the screen. And there was a desire also to go against what everyday entertainment movies do — the trend of showing an audience everything to the point of being pornographic. I don’t mean sexually pornographic, but pornographic in the sense of showing open-heart surgery in all its gory details. I feel that whenever the viewer has the impulse to turn his head or avert his eyes, these are the unnecessary scenes that have been presented. My way of framing the action actually makes the viewers sit up straighter and try to stretch their necks so they can try to see whatever I’m not showing! There are similar scenes in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s movies when he shows a character disappearing from the frame but is still talking, and you know that the character is still there, even if he’s only sensed, felt, or heard. Just like someone can be next door in the bathroom; you don’t see them, but you know they’re there. It’s that feeling that the viewer would sense the presence of a character rather than see him that I wanted to create.

JR: It’s like the idea of Bresson that whenever you can, you replace an image with a sound.

AK: In fact, I’ve studied all his films for precisely that reason.

It’s true that the world is shrinking and things are becoming more and more similar because so much is being exchanged. Everything’s being globalized: for example, when I was recently in Africa, I was looking to buy a few souvenirs to take back with me, and I saw mostly the same things I saw in Paris and other places. Things seem to be losing those specific characteristics they used to have that separate one area or nation from another. The only exception to that rule, luckily, is human nature. Certain rules govern the growth of trees; they need light, water, dirt, and air. By the same token, there are things that all people need. It’s our good fortune that all the superficial things have become so superficial that only human nature provides us with a refuge that has any depth to it.

***

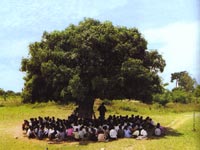

3. ABC Africa: spring 2001 (faxes between Chicago and Tehran)

JR: Do you see ABC Africa as part of your overall project to use the audience’s imagination and collaboration? It’s striking how important scenes in darkness are in your last two films. Do you think they function at all similarly?

AK: Yes, but this wasn’t a pre-planned goal. After a few days in Africa, I realized that my concept of the country, which I got from TV, was very different from what I saw. I knew an Africa that in the depths of ugliness, sickness, and filth was in the process of dying, and from that vantage point AIDS looked like a blessing that could end this tragedy as quickly as possible. But my concept of Africa was altered during the first few days. I even found the people beautiful, and the place as well — primitive but also civilized. An incredible contrast: very poor from the outside, but rich from the inside, and very much interested in life, an image that I believe is apparent in the film.

The function of darkness in the two films is identical, but in each case has its own rationale. For me, light and image can only be meaningful in relation to this darkness. We’re accustomed to images, images that are constantly in front of our eyes. Even our language tends to work with images, and naturally in the course of this visual bombardment the meaning of images is completely forgotten. I think the image recovers its meaning when it faces darkness, just as light does. In the darkness we arrive at an image through sound — an image which is based on our own experience and which therefore differs with each viewer. Every viewer creates his own image with his imagination, and this is exactly what I want, my ideal situation; the audience participates in the film’s creative mise en scene. The ideal of darkness in ABC Africa takes its form from the reality of living in darkness in Africa, without electricity, and the rainy morning after the painful seven minutes in the dark is a gift to those who have patiently tolerated the dark night until the morning.

MS: Did the Ugandans that you met know you or your films before you made your trip there? How did they react to you? How do you feel that your presence in Uganda should be read in a non-Iranian context?

AK: I don’t think that either I or anyone else who was in that strange atmosphere could remember that he was a filmmaker. They didn’t know me and I didn’t know myself. We were witnessing scenes that made a deep impression on us. It was something like the Day of Judgment. On that Judgment Day, who can remember what he does for a living?