From the Chicago Reader (April 14, 1995). I’m not sure why, but this is one of the most popular posts on this site. — J.R.

Priest

**

Directed by Antonia Bird

Written by Jimmy McGovern

With Linus Roache, Tom Wilkinson, Cathy Tyson, Robert Carlyle, James Ellis, Lesley Sharp, Robert Pugh, and Christine Tremarco.

A friend of mine who hasn’t even seen Priest calls it “post-Oprah,” and it’s easy to see what he means — in terms of pacing as well as subject matter. Its first incarnation was as a 200-page script by Jimmy McGovern for a four-part BBC miniseries, but he shaved it to 65 pages when the BBC decided to make it a feature. When it went out to festivals last year (where it won numerous awards), director Antonia Bird’s cut was 109 minutes; since then it’s been trimmed by 8 minutes, apparently to make it eligible for an R rating: its distributor, Miramax, now under the control of the Disney studio, isn’t allowed to release any NC-17 pictures. I haven’t seen the longer version, but it’s likely that these successive abridgments have both produced the taut narrative that’s central to the movie’s powerful impact as entertainment and limited it as art and as a piece of sustained thought.

Another friend who has seen Priest refers to it as “the first feel-good gay-priest movie, though probably not the last.” The priest in question is young Greg (Linus Roache), who turns up at an inner-city Liverpool parish to replace an elderly rebel. I’m not quite clear on the reasons for this priest’s dismissal, but in the film’s opening sequence, shortly after being fired from his post, he uses a five-foot crucifix as a battering ram, shattering one of the ornate windows of the bishop’s office. It’s characteristic of this movie’s quick pace and forward thrust that I either missed or forgot the transgression that got him kicked out. Perhaps the fault is mine, but given the movie’s assault on the rules and regulations of the Catholic church, it’s easy enough to fill in the blanks: most likely it was the priest’s drinking that got him into trouble.

At the presbytery Father Greg meets Father Matthew (Tom Wilkinson), another older priest, and almost immediately the political and temperamental differences between the two are spelled out, when Greg delivers his first sermon. Defining “society” as the contemporary scapegoat for people trying to shirk their moral responsibilities, Greg quickly establishes himself as a by-the-book neoconservative. Matthew — who sleeps with the presbytery’s nonwhite housekeeper, does karaoke singing at the local pub, and later gives an aggressive sermon Greg compares to “a political broadcast for the Labour Party” — has a more progressive agenda.

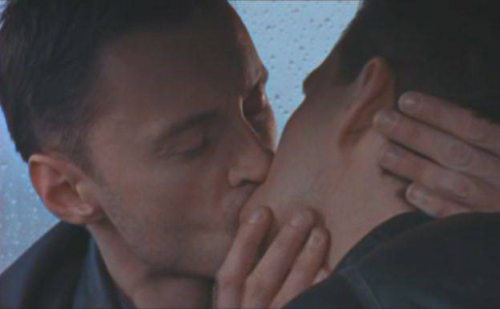

Yet for all Greg’s traditional values, he harbors a guilty secret. One night he puts on a leather jacket, rides his bike to a local gay bar, and picks up a man named Graham (Robert Carlyle); they wind up having sex in Graham’s flat. Whether Greg has done much cruising before is one of the many questions this movie doesn’t address, and it’s typical of the film that we’re not encouraged to ask. All we know is that he feels uneasy about what he’s done, and subsequently refuses to say hello to Graham on the street.

Before we’ve had any chance to ponder this further, we’re thrown another curveball. A 14-year-old girl named Lisa (Christine Tremarco) tells Greg in the confessional that her father’s been forcing her to have sex with him. “Tell him you’ve seen me, and I’ve said it’s got to stop,” Father Greg tells her; but shortly afterward, during a school performance, her father taps him on the shoulder and says, “Keep your nose out of my business.” A little later the father turns up in the confessional himself to boast to Greg: “Incest is human — it’s the most natural thing in the world.”

Unable to persuade Lisa to tell her mother what’s going on — and unable to tell the mother himself without violating the sanctity of the confessional — Greg now has two massive inner torments. These are exacerbated when Lisa has a seizure at school, and Graham turns up for mass and Greg refuses to offer him the communion wafer. To make matters worse, Lisa’s father not only winks lewdly at Greg during the school performance but appears in the confessional and then vanishes like some combination of Hannibal Lecter and an expressionist thunderclap, and when Graham marches up for his wafer, he sticks his tongue out pretty lewdly as well.

What’s confusing about all this is that Lisa’s father is supposed to be a bad guy and Graham is supposed to be a good guy. (In most post-Oprah movies there are tolerant sweetie pies and evil bigots, rarely anything in between.) So why is Graham’s extended tongue made to seem every bit as lewd as the father’s wink? I suppose it could be argued that this is Greg’s subjective impression. But these three Catholic dilemmas — violating the vow of celibacy, the homosexual taboo, and the privilege of the confessional — are supposed to have some objective reality. And the movie’s effective but souped-up presentation of this triple whammy of problems, especially when they’re being offered as parallel and virtually equivalent issues, is just rhetoric employed for short-term effects.

The sad fact is that an honest grappling with such problems isn’t necessarily compatible with a dramatic means of articulating them, and Priest invariably opts for drama. Some real-life fathers sexually molest their teenage daughters, but it seems highly unlikely that many of them would defend this practice and even brag about it to a priest. Similarly, Graham extending his tongue in such a carnal manner has nothing to do with his character and everything to do with pumping up Greg’s spiritual crisis. The advantages of such telegraphic punches, essential to television, are palpable and immediate; the long-term loss is that the characters and issues involved eventually disintegrate–sometimes before the picture’s over, sometimes shortly afterward. (Viewers who don’t want to know any more of the plot should bail out here.)

Sometimes actual events as well as characters and issues get shortchanged in these efforts to achieve drama. (Andy Roberts’s melodramatic score literally drowns out the sound track at least a couple of times, implicitly privileging Greg’s tortured consciousness over the world he inhabits.) When Greg prays aloud, hysterically, to an icon of Jesus on the cross about the continuing sexual abuse of Lisa (“Do something!”), his words continue to be heard over a scene in which Lisa’s mother catches her husband in the act; the implication is that Greg’s frantic prayer has been answered. But before we can properly take in the possibility of divine intervention, we see the mother turn up in church to tell Greg that she hopes he rots in hell because he knew what was going on and failed to tell her. Before we’ve had a chance to think much about that, Greg runs off to see Graham again and winds up getting busted with him in a car on the beach. The reason is apparently public exposure — we hear a fly being unzipped just before the cop appears — but everything happens so quickly we’re not sure: we can’t even determine why the policeman approached the car in the first place.

The movie hurtles from one outsize crisis to another, from an apparent miracle to a denunciation that seems to rule out divine intervention to an arrest that seems predicated on mental telepathy: it’s as if we were being administered a series of rude slaps. By the time Greg attempts suicide, the issue of whether the movie is challenging yet another church doctrine — suicide as a mortal sin — isn’t even addressed. Given the movie’s crowded agenda, the narrative is delivered in shorthand; in effect Priest is a feature-length trailer for the miniseries that never got made.

Shortly after I saw Priest for the second time, when I was still trying to resolve some of my feelings about it, I took another look at Alfred Hitchcock’s I Confess, a thriller made 41 years earlier. Linus Roache bears a striking resemblance to Montgomery Clift, who plays the priest in I Confess, but more important both characters undergo a sustained martyrdom because they refuse to reveal information about a crime told to them in the confessional. In I Confess the crime is murder, and when the priest becomes the prime suspect, he’s unable to clear himself by reporting the confession. (The priest also clams up about a blackmail plot hatched by the murder victim, related to the priest’s romantic escapade with a married woman before he was ordained; the Hitchcock film too has more than its share of coincidence and contrivance.)

I Confess is far from a successful picture, but it’s certainly a personal one; Hitchcock’s biographer Donald Spoto reports that the director identified closely with the murderer — in fact he wrote some of the character’s key lines and even named the murderer’s wife Alma, after his own wife. Priest also recalls The Wrong Man, a Hitchcock picture in which a prayer seems to immediately bring about the long-delayed capture of a criminal, who’s caught in the act. In fact I Confess and The Wrong Man are Hitchcock’s artiest, most pretentious pictures, dealing directly with his Catholicism; and it says something about the limitations of Hitchcock’s work as a whole that I Confess is theologically coherent but morally rather confused. Part of the problem is the masochism of the priest and the married woman and the absence of any moral center that might “place” them; Alma is the only saintly figure, but she’s too incidental to have much bearing on the leads.

Priest, on the other hand, has a certain moral coherence, preaching tolerance and inveighing against some of the less flexible Catholic prohibitions. But theologically as well as psychologically it’s something of a mess, and given all its exploitive leapfrogging from issue to issue, it’s hard to see how it could be otherwise. Despite the movie’s didacticism — most of it invective spouted by Father Matthew — it doesn’t commit to any specific reformist program, and though it eventually offers Greg some absolution when Lisa forgives him, it offers no resolutions to the conflicts in his character. The movie’s heart seems to be in the right place, yet its method is basically to beat spectators into submission, even those who are already in agreement. In interviews Jimmy McGovern has said that a major impulse behind the script was working off his resentment against the priests he encountered in Catholic schools, especially the “reactionary bastards” who administered savage beatings. Maybe that authoritarian training left more traces than he realizes.