From Film Comment (May-June 1975). -– J.R.

February 28: Heathrow Airport, London. As soon as I step on the plane, TWA’s Muzak system has seen to it that I’m already back in America. Listening on the plastic earphones to blatant hypes for GOLD on two separate channels, the soundtrack of THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT on another (where “fuck” is consistently bleeped out, but “fucker” and the sound of Jeff Bridges getting kicked in the face are dutifully preserved), it becomes evident once more that America starts and stops where its money reaches, and that “going there” means following the money trail. It’s over two years since my last visit – my longest sojourn abroad, during which I’ve had to miss the splendors of Watergate and depend on such things as Michael Arlen’s excellent TV column in The New Yorker for accounts of shifts in the national psyche — but TWA tells me in its own quiet way that nothing essential has changed.

February 28: Heathrow Airport, London. As soon as I step on the plane, TWA’s Muzak system has seen to it that I’m already back in America. Listening on the plastic earphones to blatant hypes for GOLD on two separate channels, the soundtrack of THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT on another (where “fuck” is consistently bleeped out, but “fucker” and the sound of Jeff Bridges getting kicked in the face are dutifully preserved), it becomes evident once more that America starts and stops where its money reaches, and that “going there” means following the money trail. It’s over two years since my last visit – my longest sojourn abroad, during which I’ve had to miss the splendors of Watergate and depend on such things as Michael Arlen’s excellent TV column in The New Yorker for accounts of shifts in the national psyche — but TWA tells me in its own quiet way that nothing essential has changed.

On the plane I read Pauline Kael’s pre-release rave about Altman’s NASHVILLE, and and it certainly does its job: I can’t wait to see the movie. But why does she have to embarrass everyone by comparing Altman to Joyce? It’s just about as unhelpful (and unsubstantiated) as her earlier comparisons of, say, LES ENFANTS DU PARADIS with Ulysees and THIEVES LIKE US with Faulkner, which confuse more than they clarify. Kael and Andrew Sarris have both been distressing me lately with their increasingly would-be populist positions. Kael seems to reach for literary heavyweights in order to convey the complexity of her subjects by transposing it to safer models rather than confronting it directly. While I yield to no one in my enthusiasm for recent Altman, it appears that despite her dependable arsenal of superlatives (all suitable for immediate quoting), she’s afraid to dive into a concrete, more-than-impressionistic textual analysis for fear of losing her audience, who tends to love rhetoric more than movies. Sarris, on the other hand, seems to be limiting his cinephilia nowadays to a recollection of old, familiar pleasures rather than a consideration of new and different ones. Reading last month in the Village Voice that “1974 was probably the worst year for film since 1914” and “I think it’s time we stopped kidding ourselves. Movies aren’t going anywhere in particular aesthetically,” I felt sorrow in recognizing that he and I are apparently residing on different planets. Yet I feel sympathy for his and Kael’s plight. They both have to write for masses of indifferent people about indifferent movies (e.g., MURDER ON THE ORIENT EXPRESS) as though there were some basic correlation between what is seen and what is cared about — when it’s usually a matter of where the money trail chooses to travel next. It’s a trail that you either follow or diverge from at your peril. My problem is writing mainly about movies that few people will ever see; theirs is mainly writing about movies that people talk and think about — if at all — only because they’re around and visible.

Later in the weekend, in Long Island, I try to tell the friends I’m visiting about Rivette’s OUT 1: SPECTRE, which they’ll probably never be able to see — doing what I can to describe the overall structure, the scenes between Léaud and Ogier, the content and experience of the last two shots. No critic alive has yet begun to do justice to that film — not even John Ashberv in Soho News last October, when he started off by remarking that “it seems to mark a turning point in the evolution of the art of film,” and then never got around to explaining why; certainly not myself, when I was foolish enough to call it a “dead-end experiment” in Sight and Sound last fall. But how can it ever become the turning point of anything when no more than a handful of people will ever have a chance to encounter it, much less return to it, live with it? Which is why I must keep speaking about it. . . .In the room the women come and go, speaking of AIRPORT 1975.

***

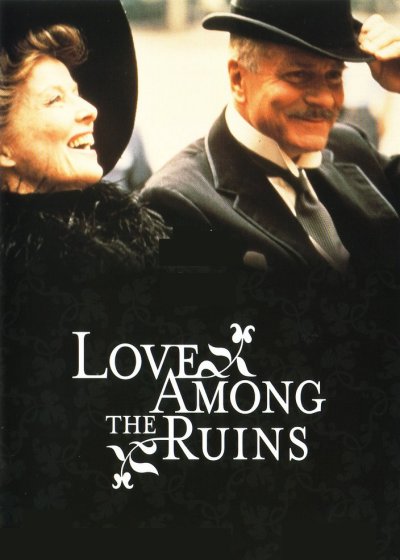

March 6: New York seems slower and friendlier this trip, as though the oncoming Depression has simplified and domesticated a lot of frantic lives. More empty cabs and prostitutes on the street, more exciting movie revivals all over Manhattan, and lots of $1 theaters, all of which I stoutly bypass as I look up lost acquaintances. But tonight I gladly capitulate to the needs of this column by catching an uncommon double-feature: my friend Harvey Marks’ intriguing, still uncompleted and untitled super-8 opus, and the premiere of George Cukor’s gently stupefying LOVE IN THE RUINS on a black and white TV set. One viewing is scarcely enough for either: l can’t attempt to read a film until after I can see it, and it takes me a while in each case to peel away misguided expectations and immediate comparisons, pursuing a respectable number of blind alleys, before I can sink comfortably into these films on their own terms. At first glance, Harvey’s film — a scrapbook collage, including bits of an unfinished fiction film, dancing and reciprocal relationships between various people and the camera, and lovely still-lifes selected from travels all over the globe – mainly demonstrates, through its variety of textures and film stocks, how supple and subtle an instrument the super-8 camera is becoming. LOVE AMONG THE RUINS offers enough of the beauty and terror of old age — OIivier’s, Hepburn’s, Cukor’s, Hollywood’s — to fill another scrapbook.

What almost seems to represent (on Cukor’s part) a remake of TRAVELS WITH MY AUNT, with Olivier assuming the Aunt Augusta role, clarifies how the relatively flat spectacle of Maggie Smith“giving her all” in TRAVELS robbed that film of the depths that leak out of this stagier production from every pore, revealing the chasms between — and occasionally the fusions of — what Olivier and Hepburn do, what they can do, whom they play, and who they are. For all the mechanical courtroom crosscutting and theatrical grandstanding, this is a movie that brings back some vestige of every Cukor-Hepburn collaboration to date and then expands upon it, with concentrated tracking shots down real or imagined 1911 London streets serving as nearly Straub-like punctuations between the lengthy interior dialogue scenes. In today’s New York Times, John J. O’Connor thoughtfully warned everyone that “even modest expectations will be disappointed”; yet it seems plausible that on a large screen before a reasonably discerning audience, even major expectations wouldn’t be. Goddam all critics who split up measured and cohesive works and then evaluate the separate pieces — the witty or unwitty lines of James Costigan, the “good” or “bad” performances — to practice Criticism Among the Ruins! Whatever its shortcomings, this movie is a whole and deserves to be seen that way. . . .When will we see it again? Only the money trail knows.

***

March 8: With a brother and sister-in-law in Washington, D.C., I finally catch up with THE HARDER THEY COME, Perry Henzell’s fabulous Jamaican political musical, in a battered pock-marked print. What immediately grabs me about this rough jewel, apart from jimmy Cliff’s powerhouse songs, is the elusive and elliptical editing of the narrative away from and into stray details, the grainy color that gives a downhome rat’s-eye view of what slickness looks like to powerless people, and the raw, melodious beauty of the non-actorly voices, which evokes some of the warm vocal sounds in Renoir’s TONI. THE HARDER THEY COME is getting shown often in Washington, and has already attracted a visible following; it’s evident that many spectators at the Outer Circle midnight show are seeing it for the second or third time.

For all its marked differences, I think that John Carpenter and Dan O’Bannon’s wonderful sci-fi comedy, DARK STAR — which I saw in London last month, and has yet to surface in the states — deserves an equivalent “cult” status, because it also gives an unforced expression of a distant ethnic sensibility: in this case, that of a particular kind of California freak. The National Film Theatre audience I saw it with loved every minute of it, and if there’s any logic or justice in the money trail, so — eventually — will you.

***

March 9: Flying south. Somewhere down there, in whatever state of coherence or incoherence, completion or incompletion, fulfillment or unfulfillment, fidelity or infidelity to Altman’s movie (which is somewhere else now, in cans), is Nashville.

March 10: Florence, Alabama. Lots of urban renewal has been going on in my home town over the past few years, and now that I’ve spent exactly half of my life — sixteen years — away from it, some of the streets are only semi-recognizable. The town’s first large movie theater, which my grandfather helped to build in 1919, was leveled long before my last visit to expand the parking lot behind the First Presbyterian Church, and the pawnshop a block away has become the House of Guns; but the plastic flowers and Muzak on the main street and Spry Funeral Home are still intact. The Shoals Theatre — which my grandfather also built, and later sold — has been remodeled, and I go to see Vincent McEveety’s THE STRONGEST MAN IN THE WORLD there mainly in order to take a look. (Just my luck: Jim McBride’s HOT TIMES has apparently come and gone in this area, and ALICE DOESN’T LIVE HERE ANYMORE is the next attraction.) The cashier’s booth, which used to have two windows to conform to the Jim Crow laws — the one on her left accommodating the black customers, who went up to the balcony for ten or fifteen cents less — now only has one. For a certain period after the Civil Rights Bill went into effect, both windows and price ranges remained to allow the old habits to linger, although theoretically any black person could pay a little more and sit downstairs, and conversely, any white person could pay less and sit in the balcony. Now the balcony’s closed, everyone sits downstairs in fewer and wider seats, and a large appreciative audience gets all that can be gotten (and then some) out of a few formula live-action Disney antics.

Despite the heroic and successful efforts of Eve Arden to remain herself in spite of everything, I leave after an hour and walk home, wondering how crazy it is to write about movies most people can’t see when I can’t last profitably through the movies that most people see. Is there a connection? As OUT 1: SPECTRE suggests about a lot of things, I suppose there is a connection and there isn’t. And whatever people are seeing — now that America seems to be inching its way ever so slowly toward the experience of most of the rest of the world — I guess it means something that people are going to movies again, proceeding wherever the money trail takes them. My family’s theater business racked up during the last Depression, and maybe — with a lot of luck and forbearance — a few good filmmakers won’t starve to death during this one.