From the Chicago Reader (July 12, 1996). — J.R.

Nightjohn

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Charles Burnett

Written by Bill Cain

With Carl Lumbly, Lorraine Toussaint, Beau Bridges, Allison Jones, Bill Cobbs, Kathleen York, Gabriel Casseus, Tom Nowicki, and Joel Thomas Traywick.

Words are freedom, old man. ‘Cause that’s all that slavery’s made of: words. Laws, deeds, passes: all they are is words. White folks got all the words, and they mean to keep them. You get some words for yourself and you be free. — the character Nightjohn

I think a strong case can be made that Charles Burnett is the most gifted and important black filmmaker this country has ever had. But there’s a fair chance you’ve never heard of him because he isn’t a hustler, he’s never had a mainstream success, and all his work to date has been difficult to pigeonhole. Born in Mississippi in 1943, though raised since infancy in Los Angeles, he was one of several key black filmmakers — including Larry Clark, Julie Dash, Haile Gerima, and Billy Woodbury — to attend UCLA’s graduate film program in the 60s and 70s. His first film to circulate widely, the remarkable 1977 Killer of Sheep, won prizes in 1981 at Berlin and Sundance (before it was known as Sundance) and was one of the first titles selected for the Library of Congress’s Historic Film Registry. But it’s never been commercially available on video, and his affecting My Brother’s Wedding (1984) is equally difficult to come by. (Both turned up most recently, along with Burnett himself, at Columbia College’s African and African-American film festival back in April.) In 1988 Burnett received a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship grant, but he hasn’t become any sort of household name since, even after moving out of the independent sector. Neither his 1990 masterpiece To Sleep With Anger, which starred Danny Glover and played the art-house circuits, nor his honorable but unexceptional 1991 TV documentary about U.S. immigration, America Becoming, has had much of an impact on the public.

Burnett himself blamed the meager promotional efforts of the Goldwyn Company, which produced To Sleep With Anger, for the lackluster reception it got in the black community. He probably had a point, though one could also argue that all of his first three features pose different versions of the same commercial dilemma: though they deal almost exclusively with the Los Angeles black community, they have few of the calling cards — apart from Glover’s presence in the third — most black viewers associate with an entertaining night at the movies. The problem is essentially stylistic: his first two features, both made independently, were inspired by the Italian neorealists and postneorealists (Ermanno Olmi’s The Tree of Wooden Clogs was a particular favorite), which probably made his work more accessible to Europeans than to Americans. To Sleep With Anger, however, is so rooted in the experience of black American rural culture that it might well have bemused European viewers. Black viewers, on the other hand, may have been put off by some of its art-movie characteristics, such as the film’s concentration on character over plot, its subtle dark humor, and its dense, literary structure. Great works, if they’re allowed time to sink in, have ways of finding and creating their own audiences, but To Sleep With Anger never had time to sink in. The consumption machine that devours and digests commercial releases weekly won’t slow down for works that take a little longer to be recognized and appreciated, and we all lost out in the process.

The Glass Shield (1994) — in which Burnett ventured for the first time into a fictional world where white as well as black characters play important roles — was a lesser movie but a more substantial commercial release, escaping art-house distribution almost entirely. This time Burnett encountered a fresh set of problems, however, almost as if he were starting from scratch. Confronting the uncomfortable issues posed when a black rookie policeman (Michael Boatman) tries to fit in at an otherwise all-white LA precinct, Burnett’s script almost seemed to anticipate some of his own difficulties in dealing with the Hollywood system. Among other problems, he had to contend with Miramax test-marketing the movie and subsequently requiring him to alter the ending before the film could be released.

Burnett’s emotionally overpowering, almost perfectly realized fifth feature, Nightjohn, is his first wholly accessible movie and unambiguous mainstream triumph — though ironically it seems to have come at the cost of increasing his anonymity. If you subscribe to the Disney Channel, you’ve already had seven opportunities to see this picture since June 1. But unless you’ve been unusually attentive, there’s a good chance you didn’t know that Burnett directed it — especially if, like me and most people I know, you depend on the listings in TV Guide and the Cable Guide, neither of which mentioned him. (I’m told that the Disney Channel program guide did better by him.) But this Saturday at the Film Center you’ll have a chance to see Nightjohn on the big screen, where it’s being shown as part of the second annual Black Harvest International Film and Video Festival, this time clearly identified as a work by Charles Burnett. (Filmed in 35-millimeter but processed in video, like many made-for-cable features, it can be seen only in the latter format, which is how the Film Center will be projecting it.)

Nightjohn is about two rebellious plantation slaves forcibly separated from their families. Nightjohn (Carl Lumbly) teaches a 12-year-old girl named Sarny (Allison Jones) how to read and write, in defiance of the law; the only other slave on the plantation who learned the alphabet, now an old man (Bill Cobbs), had a thumb and forefinger chopped off as punishment. The movie has plenty of the qualities one would expect from a Disney production, so there’s every reason to approach it circumspectly, as I did. On one level, it’s hokey, didactic, melodramatic, and contrived; compared with earlier Burnett features, the storytelling is slick, the acting punchy and declamatory. And for the first time Burnett hasn’t written his own script for a feature; the “teleplay,” loosely based on a short novel for young adults by Gary Paulsen, is by coproducer Bill Cain. Yet for all my initial doubts, the film not only grew on me but eventually won me over completely; and when I saw it a second time, a day later, it knocked me out.

The bad news is that Burnett’s fans in this country can’t count on the mass media to recognize and respond to their interest in him. Surely there’s something seriously wrong with a communications system that can’t get out the news that a new work by Burnett is available, and has been for the past six weeks — something I was made aware of only indirectly, through the Black Harvest festival. (Like many fellow Burnett enthusiasts, I’ve known that a Burnett feature for Disney was forthcoming but knew of no way to find out when.) As Nightjohn himself might put it, the folks who put out TV Guide and Cable Guide got all the words, and they mean to keep them; current and potential Burnett fans had better apply elsewhere.

The good news is that Disney, in an astonishing and apparently unprecedented move, is making Nightjohn available to everyone who wants to see it — including those who don’t subscribe to the Disney Channel and can’t make it to the Film Center on Saturday. As I learned from Burnett himself when I phoned him last week, all you have to do is call 818-569-7899 and you’ll be sent Nightjohn on video for free. (When I called the number to order a copy, it arrived by express mail the next day.) [2011 postscript: Regrettably if understandably, this generous offer only lasted for a short time.]

All you got is what you remember.

–Nightjohn

Working with a theme akin to that of Ray Bradbury’s novel (and Francois Truffaut’s film) Fahrenheit 451— though it’s given a substantially different edge by being set in the historical past rather than the projected future — Nightjohn views illiteracy as a central adjunct of slavery. Yet it isn’t merely a history lesson about people who lived some 165 years ago but a story with immediate relevance. As Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, a local filmmaker and teacher, pointed out to me, the movie often calls to mind a fairy tale — perhaps not surprisingly, given the Disney sponsorship. When I mentioned this notion to Burnett he was inclined to agree, noting that the story is told from the viewpoint of a 12-year-old girl — though he added that he didn’t want anyone to come away from Nightjohn with the impression that slavery is the stuff of fairy tales. It’s an understandable caveat: part of what’s so wonderful about the film is its use of a fairy-tale feeling to focus on real-life issues, not to evade or obfuscate them as a typical Disney product like The Hunchback of Notre Dame does. To put it somewhat differently, Nightjohn‘s fairy-tale ambience is placed at the service of myth — myth that embodies a lucid understanding of both slavery and literacy. The two lead characters, Sarny and Nightjohn, may come across at times as superhuman individuals, but the world they inhabit and seek to change is in no sense fanciful, and the emotions that dictate their actions are no less real.

The opening sequence perfectly illustrates the magical balance Burnett is able to sustain between fantasy and lucidity. Sarny, who acts as narrator, begins by saying that this is a story about Nightjohn, but it’s also a story about her. Nightjohn, she adds, told her that “‘all you got is what you remember,’ and me — I remember everything. I even remember being born.” Whether or not she remembers being born, her birth in a slave cabin is what we see next, and the dialogue in that scene offers an acute analysis of what values, economic and otherwise, come into play when a new slave is born, both to the slaves and to their master — especially in relation to color, gender, and working in the fields versus working in the house. The master, Clel Waller (Beau Bridges), enters the cabin just after the baby is delivered, smoking his pipe. “Thought you said it would be a boy,” he says to Delie (Lorraine Toussaint), the principal house slave who’s acting as midwife. Picking up Sarny, he remarks, “It dark — but she pretty,” an idiomatic expression of the fact that skin color warrants an inhuman pronoun, gender a human one. “You just cost me money, gal,” he continues — though whether he’s addressing Delie or Sarny is unclear, and perhaps irrelevant. “Boy, he grow up to be worth a thousand; can’t even give away a little gal.”

“Well, that’s good now, ain’t it?” Delie says. “‘Cause nobody givin’ this girl away. A promise been made.”

“You watch what you say, Delie,” Waller cautions her. “You’ll find yourselves in the fields and your easy days’ll be over forever.”

“Oh: you gonna make your wife run the house?” Delie responds sarcastically.

“The child stays,” Waller concludes. “But you watch yourself, Delie.” The story jumps forward a few years, to Waller selling Sarny’s mother and Delie taking over as Sarny’s de facto stepmother; Sarny says offscreen, “Delie says that my mother was beautiful” — suggesting that she doesn’t remember her birth after all — and adds that she never knew her father.

Waller is the closest thing this movie has to a villain, but as Burnett demonstrated in The Glass Shield, he’s too much a humanist to give us an unambiguous villain devoid of humanity and vulnerability, even when the villain is white and part of a corrupt system. Waller, we soon discover, is a rich man only in the sense that he owns slaves who pick his cotton. Unlike his older brother James — the favorite son who was the beneficiary of their father’s estate — he isn’t economically secure; in fact he’s deeply in debt to the local bank. We’re gradually made to feel that the power he wields over his slaves is just about the only power he has; when he’s a tyrant to his own family, it’s almost invariably over issues involving the slaves. His wife Callie — beautifully portrayed by Kathleen York as an embodiment of ineffectual yet sensitive southern white gentility — is carrying on a flirtatious epistolary affair with a Harvard graduate (Tom Nowicki) who lives a few miles away; his older son Jeffrey (Joel Thomas Traywick) is a relatively benevolent heir apparent reluctant to wield his father’s brutality; and his youngest son, Homer (John Herina), is a demonic brat whose toilet training Sarny takes over. (The pivotal role in the plot played by this training — which at one point earns Sarny a cake to take back to the other slaves — is only one indication of how far Nightjohn stretches the usual boundaries of a made-for-TV Disney feature.)

Sarny’s other main house job is spitting tobacco juice on Callie’s roses to keep off the bugs — a rather vivid example of the kind of slave work necessary to maintain southern gentility, and one of the few anecdotal details in Cain’s extraordinary script carried over intact from Gary Paulsen’s lurid short novel. Paulsen, a prolific author of children’s books, states in a note to his 1993 novel that “except for variations in time and character identification and placement, the events written in this story are true and actually happened.” Though he clearly deserves credit for providing the filmmakers with the kernel of their masterpiece, Paulsen heaps on violence and torture in a way that seems more appropriate to a Mickey Spillane novel than to Cain and Burnett’s nuanced human landscape and intricate plotting. By contrast the filmmakers use just the amount of violence needed for their story — which proves to be more than usual for a Disney picture — and not an ounce more.

As it turns out, Sarny’s stash of chewing tobacco helps pay for her first lesson from Nightjohn. Indeed, economic exchanges and their practical and ethical consequences are at the heart of this story. Nightjohn is offered to Waller for $500, but after Waller examines the slave’s back for lash scars and discovers from their abundance that he’s a troublemaker, he agrees to pay only $50, which is enough for Nightjohn but not for his clothes. I suppose this scene could be read metaphorically as a reflection of Burnett himself working for the Disney Channel, a job that a filmmaker friend has described as “paying the rent” — though Burnett gives Disney much more than an ordinary wage slave would have.

Early on we learn that not only does Nightjohn know how to read, he escaped to freedom in the north some time ago but willingly returned to the south and slavery to teach other slaves to read. This, I suppose, is the trait most likely to make the character seem superhuman — matched by Sarny’s remarkable ability to grasp the economic essentials of slavery, an understanding she displays in an exciting climactic scene with a sophistication unlikely in most adults. But it’s a tribute to Lumbly’s performance (he also played the very different part of the elder brother in To Sleep With Anger) that we accept his passionate commitment as real. Surely his involvement isn’t radically different from the commitment of northern blacks who went south to work in the civil rights movement 130 years later. And to the degree that we can accept Nightjohn and Sarny as real — and see their story as some version of our own, whatever our form of enslavement — Nightjohn functions as a revolutionary film.

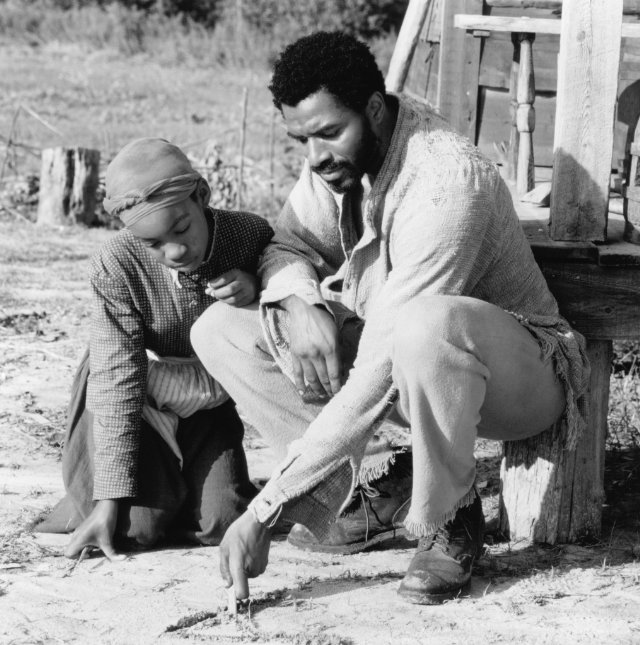

My lesson’s got no bottom at all [drawing an A in the dirt]. It stands on its own two feet. — Nightjohn

Why is literacy deemed so essential to liberation in Nightjohn? Arguably it played less of a role in the civil rights movement of the 60s than it should have, and it would be hard to argue that it plays much of a part in what passes for American leftist rhetoric today, particularly in the postliterate and subliterate world this movie is addressing. Paradoxically, literacy is called into play in this movie — with its references to Dickens, Tom Jones, and epistolary romances — much more often than it is in the source novel.

Nightjohn’s statement that words are freedom isn’t simply a slogan intended to make slavery taste sweeter; the significance of reading and writing in this movie is never abstract — repeatedly these are the means for finding where you are and what you can do to change the world and yourself. As the movie makes clear, there are separate but connected kinds of knowledge to be gained from letters and words and numbers; the many economic lessons the movie offers — only a few of which I’ve mentioned here — are part of this knowledge. Reading a newspaper story allows Sarny and the other slaves to learn about Nat Turner, the black revolutionary who led an army of 60 fellow slaves to kill almost as many white people (the only historical event alluded to in the film, making it possible to place most of the action around 1831). The movie gives a lot of attention to the relationship between reading and religion: when Sarny declares in church that she’s been “saved,” she’s obviously talking about her recently acquired ability to read. And the film points to some of the complex ironies surrounding her education — and black Christianity in general — by showing Sarny stealing the white minister’s Bible around the same time that she’s baptized.

The ability to write means that two passes can be forged, allowing a slave couple to escape to freedom. And for Nightjohn (whose father learned how to write his own name without achieving literacy), literacy becomes the seal of his own identity: if A represents what he is and what he does — standing on his own two feet and opening up a universe “with no bottom at all” — B reminds him of his lost wife, whom he’s still hoping to find. For Sarny, reading the master’s ledger and the mistress’s love letters means learning not only who your master and mistress are but what you can do with this knowledge — even what you can get away with. Considering what Cain and Burnett have gotten away with in the very belly of the Disney beast, it’s a lesson well worth attending to.