Here, for a change, is a double header — reviews of two films I’m especially fond of, both by Bob Balaban, made and reviewed about six years apart, Parents and The Last Good Time.

From the Chicago Reader (April 7, 1989). — J.R.

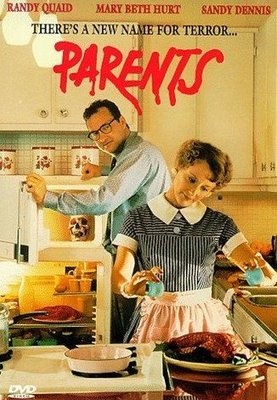

PARENTS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Bob Balaban

Written by Christopher Hawthorne

With Randy Quaid, Mary Beth Hurt, Bryan Madorsky, Sandy Dennis, Juno Mills-Cockell, Kathryn Grody, Deborah Rush, and Graham Jarvis.

Having already opened and speedily closed in both Los Angeles and New York, Parents arrives in Chicago under a bit of a cloud. Brilliant but uneven, this ambitious feature doesn’t have a script that’s worthy of its high-powered direction, doesn’t build as dramatically as it might have, and clearly bites off more than it can chew. But it is still the most interesting and exciting directorial debut that I have encountered in some time — a “failure” that makes most recent successes seem like cold mush. Choosing a movie to take with me to a desert island, I would opt without a second’s hesitation for Parents over such relatively predictable Oscar-mongering exercises as Rain Man, The Accidental Tourist, or Dangerous Liaisons, because it’s a movie that kept me fascinated, guessing, and curious — even when it irritated me.

Parents is the first feature directed by native Chicagoan Bob Balaban, whose previous directing credits include a short (SPFX), the pilot episode of the TV series Tales From the Darkside, an Amazing Stories segment, and a Showtime special built around comic magicians Penn and Teller. He’s also had wide exposure as an actor, even if few moviegoers seem to recall him by name. Onstage, he started out as Linus in You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown, and he most recently appeared in David Mamet’s Speed-the-Plow on Broadway. His movie roles include the kid who propositions Jon Voight in a Times Square movie house in Midnight Cowboy, the prosecuting attorney in Prince of the City, scientists in at least three films (Altered States, 2010, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, where his character was also the Francois Truffaut character’s interpreter), a government investigator in Absence of Malice, and a parole officer in the current Dead Bang. His diary of the shooting of Close Encounters, brought out in paperback in 1978, makes for a good and intelligent read.

One of the clear benefits of this background is his deft handling of actors — not only professionals like Randy Quaid, Mary Beth Hurt, and Sandy Dennis, but the inexperienced Bryan Madorsky, who plays the movie’s ten-year-old hero, Michael, and the only partially experienced Juno Mills-Cockell, who plays his best friend. The unexpected, lyrical freshness of Madorsky and Mills-Cockell is effectively set off by the mannerist caricatures of Quaid and Hurt, as the hero’s parents, and by Dennis, who plays a neurotic but sympathetic grammar-school psychologist. Dennis’s character exists halfway between the kids and the parents, sharing the shy awkwardness of the former and the age and size of the latter.

One thing that all these characters have in common is that Balaban presents them more as distilled essences than as fluid, changing personalities, much as a ten-year-old boy might perceive himself and others. In fact, much of what is most exciting about Parents stylistically is its expressionism, which focuses more on impressions, situations, and atmospheres than on unfolding events or plot twists; it is only when the film belatedly begins to follow conventional guidelines of genre and narrative that it finds itself in trouble.

Consider the movie’s extended opening, which deftly establishes Balaban’s unusual approach to atmosphere and narrative continuity. As the credits begin, set to the strains of that nauseating 50s pop instrumental, “Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White,” we see aerial shots of endless reaches of identical ranch-style houses, succeeded by a huge close-up of the front of a moving blue 50s-era Oldsmobile; the film’s title appears over the grille and then breaks apart, like taffy or chewing gum.

We cut to the car’s interior, stuffed with a family and its possessions. Lily Laemle (Mary Beth Hurt), sitting in the front seat, is prattling on to her son, Michael, in the back about how glad she is that they have moved, while her husband, Nick (Randy Quaid), drives. A subjective shot of the passing neighborhood (under Madorsky’s credit) is followed by a frontal shot of tiny Michael, surrounded by luggage and looking out the windows on both sides with his liquid eyes, which establishes the film’s overall vision as being very closely allied with his own. Three more shots are devoted to the utter unctuousness of a crossing guard, who draws the car to a halt so that schoolchildren can pass, and of Michael’s parents, who wave back at him with petrified cheeriness.

Then the prologue continues with a long series of incidents — some consecutive, some spread out over an extended period of time. The overall effect is oddly eventless, because the unannounced temporal leaps and the similar lengths of the shots make each incident seem equivalent to every other, regardless of whether they are narrative events or more general behavioral descriptions of the characters. In quick succession, we see Michael’s new school as the Laemles drive past it, a static shot of their ugly new house, Lily and Nick (now fully settled in) essaying a mambo in their living room, Lily planting blotches of white icing on a hideous pink cake, Nick putting a golf ball across the living-room floor, Nick and Lily ritualistically attending to their outdoor barbecue, a close-up of the repulsive meat being delivered by Lily on a tray to husband and son at the dinner table, and finally — over Balaban’s directorial credit and the last phrase of the instrumental — an exterior shot of their house at night.

This is followed, in turn, by a shot of Michael’s profile in extreme foreground as he sits on the living-room floor, lost in thought, with his parents much farther back, in the dining room — striking low-angle, deep-focus, wide-angle composition. In fact, throughout the latter part of this long introductory sequence, Balaban’s use of low angles and distorting wide- angle lenses recalls some of the eerie spatial effects used by Stanley Kubrick and Raul Ruiz, as well as Kubrick’s and Ruiz’s main precursor, Orson Welles. (In particular, this profile shot is a dead ringer for many to be found in Ruiz’s child-oriented films, such as City of Pirates and Manoel on the Island of Wonders.) Critic Manny Farber once wrote that Welles’s “efforts with space” in Touch of Evil were “to make it prismatic and a quagmire at the same time,” and this precisely describes Balaban’s vision in Parents as it is structured around Michael’s alienated viewpoint. This vision leads to the depiction of Nick, the father, as an overbearing gargoyle, the spread-out, long-skirted, flowery effect of the mother, Lily, and the cavernous reaches of the Laemles’ house seen as both a performing arena and a confining trap.

The overblown tackiness of the film is more poetic and atmospheric than literal, and when the focus eventually shifts to Michael’s nightmares (which involve blood, meat, and a confused notion of what his parents do together late at night), we can accept them as a logical extension of the overall vision. It’s only when we are obliged to take his nightmares as the literal truth that the poetics start to come apart, and so does the film.

It’s not difficult to accept Michael’s parents as metaphorical cannibals whose appetites for food and sex are somehow intertwined. All the other adults in the community — apart from Millie Dew (Sandy Dennis), the school psychologist — including Michael’s teacher and Nick and Lily’s friends, are equally grotesque and sinister, as is the world that they inhabit and the culture they espouse. (Nick is a defoliant expert at a plant called Toxico.) But when Michael’s nightmares prove to be real, and we’re asked to accept Nick and Lily as literal cannibals (unlike their neighbors), the poetic metaphor no longer applies — the clanking machinery of formulaic horror movies takes over, complete with accompanying cliches. Even in a satirical context, the notions of secrecy and paranoia appear a bit displaced: in the late 50s, when the film is set, Nick’s work as a defoliant expert would have been more secret than the movie makes it out to be; instead the movie’s notion of secrecy is restricted to the home — to Nick and Lily’s sexuality and cannibalism, which are treated as being related satirically (if not literally) to Nick’s profession. The problem, in other words, is that the film’s uses of satire and poetic metaphors, its plot and its “program,” aren’t always compatible.

It’s hard to know whether to blame Christopher Hawthorne’s script for this or some more general flaw in Balaban’s conception. Perhaps the real problem isn’t the filmmakers’ deliberations at all but the cannibalistic demands of the commercial marketplace, which decree that any plot, no matter how silly or hackneyed, is preferable to no plot at all. It’s possible, in other words, that Balaban and Hawthorne may have been obliged to degrade their overall conception simply in order to be able to make this movie.

Parents suffers as well as triumphs because of its opposition to certain cherished ideas. One of these received notions, adopted most commonly by spectators born in the 60s or later, is that the 1950s in this country were a kind of golden age, which we can now look back upon as a lost paradise. (A few years ago, when I was teaching film at the University of California in Santa Barbara, my course in Hollywood films of the 50s was especially popular for just this reason. When I asked students what made the 50s seem so attractive to them, they usually cited prosperity and the importance of traditional family values — the former based on their false impression that the U.S. economy was in better shape in the 50s than in the 60s.) Anyone who continues to believe that today is likely to experience Parents as a solid kick in the teeth, which is all to its credit.

The other received idea, even more widespread and ingrown, is that movies should be made exclusively in popular genres and with familiar stories. This movie, however, remains original and exciting only as long as it manages to elude conventional story telling and goes straight down the tubes as soon as it capitulates to it.

The connection between these two ideas might be pointed up by a look at two of the films of David Lynch, whose style and vision provide a telling cross-reference to that of Balaban in Parents, and whom critics everywhere have been evoking in discussions of Parents. The brilliance of Lynch’s first feature, Eraserhead, largely depends on its nonnarrative aspects, while the much greater popularity of his Blue Velvet depends on both its adoption of a more conventional story line and its ironic evocations of the 50s as a period of blissful and wholesome innocence — a notion the film somehow manages both to subscribe to and to undermine without ever forcing the audience to deal directly with this contradiction.

Broadly speaking, in Eraserhead as well as in Blue Velvet, Lynch remains an “apolitical” filmmaker, which in the context of the 70s and 80s means a politically conservative one: resolutely nonanalytical, virtually Manichaean in his treatment of women (all of whom are either “good” girls or “bad” — i.e., sexy), a biological determinist in his view of sex and procreation, a voyeuristic puritan in relation to both sex and violence (which, in Blue Velvet, go together like ham and eggs), and a reactionary in his purely nostalgic relation to the past. The fact that he nonetheless appeals more to liberals than to conservatives can perhaps be explained by the kinkiness of his worldview, a kinkiness that is almost impossible to find in leftist artists.

Before it takes its nosedive into incoherence, Parents can’t be accused of having any of these retrogressive traits — which makes it so incongruous that critics have been linking this movie so insistently to Lynch. (The film’s poor commercial showing in both New York and Los Angeles also suggests that critics who have been linking it to Lynch aren’t necessarily doing it any favors, either.) Far from being nostalgic about the 50s (i.e., the present) like Blue Velvet, Parents is corrosively analytical about the subject, and there’s no real innocence to be found or celebrated here; even Michael has too much of a morbid streak to qualify as “pure” (like the Laura Dern character in Blue Velvet).

Ironically, Balaban’s sense of the awfulness of the physical and spiritual decor of the 50s is much closer in some ways to that of John Waters, even if Balaban considers negative the same cultural detritus that Waters’s camp sensibility would define as a plus. Ultimately, the least fashionable aspect of Parents may finally be what’s most important and interesting about it — that its aesthetic biases are not only related to its moral, social, and political biases, but interchangeable with them. This gives Parents a certain conceptual integrity even when it flounders, as satire or as a horror movie, and suggests that if Balaban manages to get ahold of better material in the future, we might be in for some genuine revelations.

Sex and the Single Codger (THE LAST GOOD TIME)

This appeared in the May 5, 1995 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

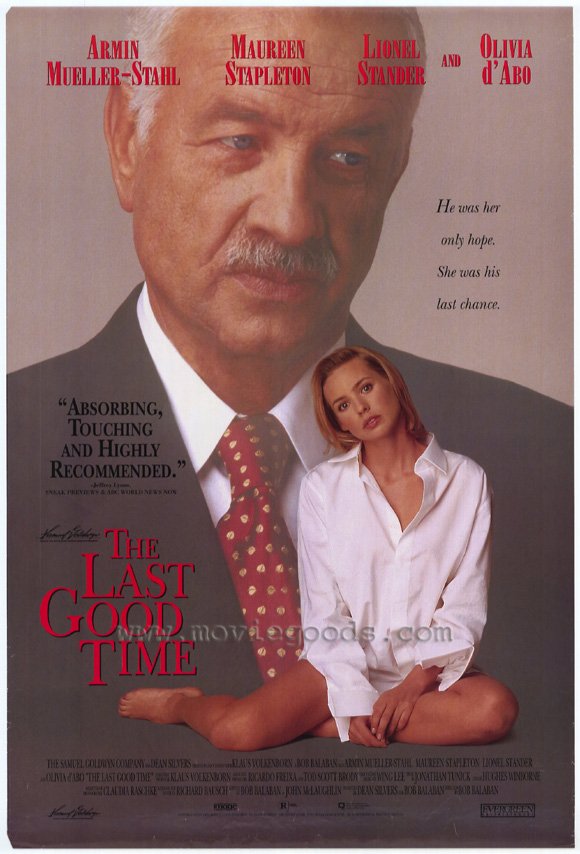

The Last Good Time

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Bob Balaban

Written by Balaban and John McLaughlin

With Armin Mueller-Stahl,Olivia d’Abo, Lionel Stander,Maureen Stapleton, Kevin Corrigan, Adrian Pasdar, and Zohra Lampert.

Bob Balaban, a native Chicagoan who’s best known as a prolific movie and stage actor, has directed only three features to date. I haven’t seen his second feature, My Boyfriend’s Back (1993), which some people tell me I’m better off having missed, but Parents, his first, was one of the most auspicious debuts of 1989.

Despite the radical differences between Parents and The Last Good Time in terms of genre, subject, style, and tone, they’re clearly the work of the same filmmaker. Part of this has to do with a precise feeling for place and a profound grasp of what sitting alone in a room feels like, even when other people are present. The solitary character in Parents is a ten-year-old boy who’s living with his parents in tacky 50s American suburbia. The monstrous (if typical) ranch-style house where they live is seen basically just as the boy experiences it — an expressionist, wide-angle nightmare etched in “cherry pink and apple blossom white” (to quote the song heard over the opening credits) that matches his parents’ taste and hypocrisy.

In The Last Good Time the solitary character is a retired immigrant violinist and childless widower named Joseph Kopple (Armin Mueller-Stahl), who’s living in a decrepit and anonymous (if typical) one-room apartment in Brooklyn. This space isn’t expressionistic or stylized in any obvious way, yet it’s amazing how expressive Balaban and his production designer, Wing Lee, make it; indeed, it’s made to say quite different things about Kopple at various times over the course of the film. Suggesting an expressionism that’s internalized and minimalist, this simply and starkly appointed space is something we experience as the inside of Kopple’s head, and the complex camera maneuvers performed within this apparently constricted arena manage to keep it both fresh and familiar, like thoughts that are both recurring and evolving. Thanks to Balaban’s compositions, which had a comparable pristine power in Parents, these thoughts are arranged before us like items in a Joseph Cornell box.

Based on a novel by Richard Bausch, The Last Good Time is as much about what it means to grow old in the 90s as Parents was about what it meant to grow up in the 50s, only this time the story is much more shaped and controlled. The plot centers on the changes in Kopple’s life when he takes in Charlotte (Olivia d’Abo), a 22-year-old neighbor from upstairs who’s physically abused by her shady boyfriend and then accidentally locked out of their apartment. Kopple allows her to sleep on his floor, and their physical proximity as well as their radical differences create an evolving dance of interactions. The film is preternaturally attuned to this dance, and Balaban’s charting of the erotics of this developing relationship couldn’t be more alert and judicious. This is a very sexy movie and a very funny one, but its definitions of what’s sexy and what’s funny aren’t standard. Furthermore it’s a movie that knows exactly where it’s going every step of the way, and every scene and shot has a specific point to make — a kind of precision filmmaking we rarely encounter these days.

An approach that is this acutely aware of itself is clearly limited when it comes to spontaneity. But it’s part of Balaban’s achievement that he never overshoots his mark by trying to go beyond what his material has to offer. Emotionally and thematically, this is a perfectly measured movie; it always knows when to cut and when to keep the camera running, it never allows a scene to become unduly rhetorical or sentimental, and it always remains entirely believable. In many respects these qualities perfectly match the control-freak personality of Kopple himself, who makes out a list not only of what to do every day but of what to wear. They also reflect the parsimonious lifestyle assumed by — and often forced on — the elderly: having to estimate how much energy one needs to get up or down a flight of stairs, for instance, is a problem that rules much of the life of Ida (Maureen Stapleton), another upstairs neighbor of Kopple’s whose solitary life contrasts with and parallels his own. (It’s a poignant moment when Ida angrily denounces Kopple in his flat for his mean-spiritedness, then has to knock at his door again to solicit his help in climbing back up the stairs.)

Economies of diverse kinds rule Kopple’s life, including economies of money, energy, memory, emotion, and philosophy (which is mainly what he reads). He tends to save what Charlotte and her obnoxious boyfriend squander, but this doesn’t necessarily mean he’s any more realistic or flexible than they are. Near the beginning of the film he’s told by a woman working for the IRS that his pension is taxable and he therefore owes the government $6,000, his entire savings; for the remainder of the movie he tries to cope with this dilemma, and part of his response is simply denial. His memory of the past is concentrated on an image of his late wife (whose picture is the only thing hanging on his wall) dancing naked before a fireplace, and his life in the present seems comparably organized around a few reliable staples. A pro like Mueller-Stahl knows this character like the back of his hand, but, like Kopple himself, he isn’t in any hurry to tell you everything he knows right away.

There are very few Hollywood movies that deal in any depth with the everyday life of old people, because, needless to say, it isn’t a subject that attracts audiences. Leo McCarey’s sublime Make Way for Tomorrow (1937) may be his greatest picture, but it was his screwball comedy of the same year, The Awful Truth, that drew the crowds and won him his first Oscar. Part of the beauty of The Last Good Time in approaching this subject is that it doesn’t try to say too much about it; it merely asks us to sit with it for a while, look at it this way and that, and arrive at a few modest conclusions. Some of these conclusions have to do with the way old people are treated in this country, but the film never mounts a soapbox; it merely allows us to see this with more clarity than usual.

The movie features the last screen performance of the late Lionel Stander, one of the greatest of all character actors — a gravel-voiced wonder with gnomelike features, sensitive eyes, and a simian brow. He flourished in 30s and 40s movies by Ben Hecht, Frank Capra, Howard Hawks, Fritz Lang, Leo McCarey, and Preston Sturges, among others, but the Hollywood blacklist drove him overseas for most of the 50s and 60s, when he wasn’t working as a Wall Street broker. (Some of his most notable later performances were inThe Loved One, Cul-de-sac, Once Upon a Time in the West, and New York, New York.) Balaban’s creating the opportunity for Stander to deliver such a perfect swan song is justification enough for this movie, but it’s a blessing that’s interconnected with the film’s other virtues; it’s another factor in the overall economy.

The character Stander plays here, Howard Singer, is Kopple’s former upstairs neighbor and only friend. He’s dying in a rest home, and the fact that Stander, born in 1908, was close to death himself clearly adds something to the size of his performance — not a trace of morbidity, which one might assume, but rather wisdom, humor, honesty, and eloquence as both the character and the actor stare death in the eye. (Something comparable comes across in Richard Bennett’s performance in The Magnificent Ambersons, though on a smaller scale; Stander takes over the film every time he appears, and he never squanders the opportunity.) Howard Singer’s memory is constantly slipping away, and he’s usually aware of this. He’s largely preoccupied with sex, which probably isn’t uncommon for someone his age, though it flies in the face of what most people expect from him. There’s a matter-of-factness about this character and this performance that’s as beautiful and as functional in the film as the simplicity and perfection of Kopple’s apartment.

In his own life Stander was something of a good-time Charlie, and Howard Singer shares this capacity. (In a 1971 interview Stander said, “There were blacklisted actors who committed suicide….But me, I have always lived on the champagne level. I figured that I needed $1,250 a week to break even, so I went to work on Wall Street, where there is no blacklist. I became a customer’s man, and I managed to live in the style to which Hollywood had accustomed me.”) When Kopple gets laid he brings a bottle of booze and cigars to the rest home to celebrate his triumph with Singer. His friend offers a toast: “Here’s to your liver and your dick.” It’s one of the nicest aspects of The Last Good Time that the precise meaning of the title remains pointedly ambiguous, though there’s clearly a suggestion that good times occasionally last longer — and come later — than they’re supposed to.