From the Chicago Reader (May 11, 1990). — J.R.

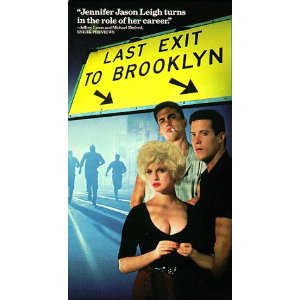

LAST EXIT TO BROOKLYN

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Uli Edel

Written by Desmond Nakano

With Stephen Lang, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Burt Young, Peter Dobson, Jerry Orbach, and Alexis Arquette.

After making the rounds of Europe late last year, this West German feature, an adaptation in English of Hubert Selby Jr.’s famous short-story collection of 1964, has finally reached our shores, and it proves to be at least as much of a mixed blessing as the book itself was a quarter of a century ago. Although shot on location in Brooklyn’s Red Hook district, adapted by an American (Desmond Nakano, who scripted Boulevard Nights about a decade ago), and featuring an all-American cast, this is very much a European picture in style and ambience, with more emphasis on mood and atmosphere than on plot and action.

Uli Edel, the director, whose best-known previous effort in the U.S. is Christiane F. (1980), and who has been interested in adapting this book since the early 70s, employs a somewhat distanced theatrical style in lighting, production design, and staging that registers a bit like Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s did, though without the political irony that gave Fassbinder’s style its edge. The relative distance from which Edel views the action is welcome, in any case, because given the horrific nature of Selby’s universe, the film would be unbearable without it.

Back in the 60s, I read only one of the six stories in Selby’s book– “Tralala,” which is about a teenaged hooker and which occasioned a celebrated obscenity trial when the Provincetown Review published it in 1961 — and I was dissuaded from reading farther. As powerful as this story was, its sledgehammer aesthetics were more brutalizing than sensitizing, and while it had all the authenticity of a personally conducted tour of hell, it left me feeling bruised but not wiser. In comparison to, say, James T. Farrell’s heartbreaking short story “The Scarecrow,” which deals with a related subject, “Tralala” has the effect of a bludgeon.

Written in a vernacular, beat-influenced, run-on style — closer to Allen Ginsberg than to Jack Kerouac or William S. Burroughs, but personal enough to have a pace and rhythm of its own — “Tralala” relates the brutal career of a hooker named Tralala in a single unbroken paragraph. The story is a catalog of cruelties — cruelties that are initially inflicted by the heroine (who rolls drunk soldiers and seamen or sets them up to be rolled) and at the end are inflicted upon her. We know nothing about her family or her psychology (apart from her nihilistic avarice and her pride in her “big tits”), and, to Selby’s credit, there is no pseudomoralistic implication that her own eventual suffering represents comeuppance: the tone of moral ugliness and meaningless suffering remains pretty much the same throughout.

In one episode, for instance, Tralala knocks a soldier with a wounded leg unconscious. Angry and impatient that he has wanted to spend a whole hour talking to her, she pockets his cash and throws away his wallet. When he turns up later at the bar where he initially picked her up, begging for his ID card, she and a couple of hoods stuff his bloody handkerchief into his mouth and beat him to a pulp. “Before they left Tralala stomped on his face until both eyes were bleeding and his nose was split and broken and kicked him a few times in the balls”; when they later hear that he might go blind in one eye, they all enjoy a good laugh. About 15 pages later, in a single sentence that extends for about four pages, Tralala is gang-raped, tortured, mutilated, and possibly killed in a vacant lot; four of her acquaintances look at her broken body and roar with laughter.

I’m fully aware that Selby’s prose is by design and in principle a cry of rage and horror against such nastiness, but in practice it seems to come much closer to a masochistic celebration of it, which is not all that far off from what is branded simple fascism in the work of someone like Mickey Spillane. As critic Tony Tanner puts it, “The comparative absence of stylistic resistance to such hellish conditions makes Selby’s book rather demoralizing.”

Consequently, I have to confess that I’m more grateful than indignant that the filmmakers have decided to tone down the “Tralala” section considerably, even leavening it with some improbable sentimentality at the end, although it remains disturbing. (Whether its toned-down form makes any more sense is a separate question.)

Combining half a dozen stories with only a few overlaps in characters can’t have been a simple task, and while Nakano’s script isn’t completely coherent, it generally does a good job of unifying the material. What emerges are several distinct but parallel plot lines that merge occasionally. Though the time frame of the original stories stretches from World War II to the early or middle 50s, the film is set in 1952, and all the events take place within a relatively short period of time.

Apart from Tralala (Jennifer Jason Leigh), the other major characters include her pimp, Vinnie (Peter Dobson); a male drug addict named Georgette (Alexis Arquette) who is attracted to Vinnie; Harry Black (Stephen Lang), a shop steward with a wife and baby who becomes interested in a gold-digging homosexual during a steel strike; Boyce (Jerry Orbach), the union leader; Big Joe (Burt Young), one of the strikers; Big Joe’s pregnant daughter Donna (Ricki Lake) and his coworker Tommy (John Costelloe), who may have caused Donna’s pregnancy and who is persuaded to marry her; and to round out the circle, Big Joe’s son Spook (Cameron Johann), who has a schoolboy crush on Tralala.

The steel strike is the subject of the longest story in the book, “Strike,” and although Nakano has done a good job of connecting it with the other plot strands, he hasn’t managed to make the strike very meaningful in its own right. (We never get much sense of what issues are at stake or how they get resolved, so this portion of the film doesn’t have much focus.) Tralala has been made into a figure resembling Marilyn Monroe, and although Jennifer Jason Leigh does a decent enough job of playing her, the script doesn’t give her much to work with. (Her role as a Florida hooker in Miami Blues is a lot more substantial.) Similarly, Stephen Lang does a creditable job as Harry Black, and if the screenplay eventually pushes him into the pretentious role of a crucified Christ figure — after he sexually molests a 10-year-old boy, some of the neighborhood punks stomp him to smithereens, hang him on the crossbars behind a billboard, and beat him some more — this is a meaning that can be traced directly back to Selby’s original. (We’re spared, however, Harry’s overripe last words to himself in the story, which are not, “O God, why hast Thou forsaken me?” but “GOD . . . GOD . . . YOU SUCK COCK.”)

Some of what remains is grimy slum humor: Big Joe, unable to get into the bathroom to relieve himself, pisses out the window, and winds up splattering a baby; Donna’s water breaks while she’s being fitted with her wedding dress. But most of the rest is pure unalleviated horror, such as the moment when Georgette, stumbling out of a heroin stupor, is struck and killed by a speeding car. The only irony in this is a grim little detail in the casting, which seems to make a relevant observation about Last Exit to Brooklyn as a whole: the driver of the speeding car, who is horrified by what he has done, is played by Selby himself.