Written for Trafic no. 26, Summer 1998, and published there in French translation; it has also appeared in English in the collection I coedited with Adrian Martin, Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia. – J.R.

This year [1998] the Rotterdam Film Festival ran for twelve days in late January and early February. But I could only attend the first half — five days apart from opening night. And thanks to a vidéothèque at the festival with copies of most of the films being shown -– including many that were scheduled for the festival’s second half -– l found myself alternating most days between screenings at the Pathé and the Lantaren, the festival’s two multiplexes, where I was always watching something with an audience (between twenty and several hundred people), and solitary sessions with earphones at the vidéothèque (located on the ground floor of the Hotel Central, which served as Gestapo headquarters during the war).

A few other facts: I managed to see about forty films and videos, but only ten of these were full features; I also, for one reason or another, walked out of or only sampled five other features at the multiplexes and wound up fast-forwarding my way through one other feature at the Central – Gunnar Bergdahl’s documentary The Voice of Bergman (1997), where I went looking for Bergman’s dismissal of Dreyer as a filmmaker who made only two films of value, The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) and Day of Wrath (1943). (As it turns out, Bergman doesn’t even bother to support this judgment with any argument, except to insist on the vast superiority of Jan Troell.)

I’m bringing up this sort of information in order to clarify a few important considerations:

1. All over the world today, critics, teachers and students frequently watch films alone on video and then write or talk about these films as if they saw them collectively in a cinema. It’s a casualty of living through a transitional period, and it often involves a kind of imprecision and a certain imposture regarding our own relation to these films. That is, when we say what a film is attempt to describe it we generally regard it as an object abstracted from its performance and reception, yet the circumstances of that performance and reception often mold our perceptions of the film as an object.

2. It might be argued, in short, that my mode of reception (and perception) has some things in common with, sampling in popular music –the way a disc jockey passes between fragments from separate records, using transitions that by cinematic analogy range from abrupt cuts to lap dissolves.

3. A broader consideration: every trip that l take to Europe from the U.S. nowadays affords me the pleasure of experiencing relief from the self-fulfilling and self-serving prophecies of American commerce, especially those relating to cinema and what might be termed ‘narrative correctness’. A few of these glib formulas: Hollywood simply gives the public what it wants. (First lie: that Hollywood — or the public, for that matter — knows what the public wants. Second lie: that what the public wants can necessarily be gauged by how it spends money.) The public only wants to see Hollywood genre movies. (See above.) Ergo, everything that can’t be described as a Hollywood genre film is of marginal interest and importance.

The worst consequence of ‘narrative correctness’ as it has entered critical discourse is an identification with producers and distributors rather than filmmakers, so that critics are now prone to recommend the same sort of artistically damaging recutting that producers sometimes carry out. I actually know two highly respected critics in the U.S. – one American, one Iranian –who have tried to persuade Kiarostami to remove the final sequence from his sublime Taste of Cherry (1997); and in the case of Robert Duvall’s The Apostle (1997), reviews of its screenings at festivals that suggested it would be “improved” by cuts eventually resulted in the removal of seventeen minutes by Walter Murch before the film opened commercially anywhere. And even though Murch’s recutting was sensitive and thoughtful, the style of the film was altered somewhat; what initially resembled at times a Jean Rouch documentary has been thoroughly narrativized — narrative correctness with a vengeance, all ultimately derived from the mythology of “giving the public what it wants”.

So for me a particular pleasure of attending the Rotterdam Film Festival year after year — and this is the thirteenth festival I’ve attended since 1984 — is the pleasure of seeing the received wisdom of American commerce repeatedly confounded. To all appearances, there’s a hunger for experimental work that producers, distributors and most mainstream reviewers are completely unaware of, and which gives me a renewed faith in the capacities of spectators.

The late Huub Bals, who founded the festival and defined its spirit until his death in 1988, was certainly open to most kinds of transgressive cinema, but the tradition of non-narrative cinema represented by such figures as Ernie Gehr, Ken Jacobs and Rose Lowder eluded him. A passionate visionary who was not quite an intellectual, Bals resembled Henri Langlois in his reliance on intuition and in his adherence to a French notion of the avant-garde that was, at that time, warmer to Philippe Garrel and Raul Ruiz than to Michael Snow and Hollis Frampton.

Marco Müller, Bals’ first successor (1990-1) — a genuine intellectual and scholar with a winder range of reference points, and the only Rotterdam festival director to date with a pronounced interest in publishing books and monographs to accompany his programs (a project he now sustains at Locarno) altered this emphasis by inviting to Rotterdam such American experimental filmmakers as Leslie Thornton and Laurie Dunphy, but in contrast Emile Fallaux (1992-6), a documentary filmmaker with more interest in subject matter than in formal or historical issues, tended to avoid or marginalize difficult works. (Significantly, unlike his predecessors and successor, he systematically excluded Straub and Huillet’s films from his festivals.)

Simon Field, who, like Fallaux, has presided over the festival’s expansion, combines some of the interests of all his predecessors. But as a specialist in experimental cinema who founded and coedited the irreplaceable Afterimage in London — perhaps the most consistently interesting experimental film magazine England has ever had during its approximately twelve years and fifteen years of publication (1970-85) — Field this year succeeded in popularizing experimental cinema at Rotterdam in an unprecedented fashion. Part of this came about through the opening in 1997 of the Pathé — the largest multiplex in Holland and probably the best designed that I know of anywhere, which quickly became the center of the festival last year — and Field’s decision this year to program many of the more accessible experimental films there. (By contrast, the Gehr films were shown only at the Lantaren — an older kind of multiplex that used to show nearly all of the festival’s films through the mid 80s, until commercial cinemas began to be used more prominently.)

In some respects, the Pathé suggests an airport or a train station where crowds are periodically appearing and disappearing between scheduled departures; in other respects, it recalls superstores like Virgin or FNAC – or, in the U.S., bookstores like Borders and Barnes and Noble — that have become the capitalist replacements for state-run arts centers or public libraries. The disturbing aspect of these stores as replacements of this kind is the further breakdown of any distinction between culture and advertising which already characterizes urban society in general. But a positive aspect may also exist in terms of community and collective emotion.

Paris flashback #1: Thanks to saving my appointment books, I can pinpoint that the “nuit blanche” devoted to New America Cinema at the Olympia Cinema started at midnight on December 4, 1971, and that I somehow managed to see only three films there: Michael Snow’s Back and Forth (1969), George Kuchar’s Hold Me While I’m Naked (1966), and Bruce Baillie’s Mass for the Dakota Sioux (1963-64). I didn’t succeed in seeing the films shown there by Ron Rice, Jonas Mekas, Peter Kubelka, Ken Jacobs, Hollis Frampton, Stan Brakhage and Kenneth Anger because the overall experience, as I recall it today, was rather like attending a riot — perhaps the closest thing I’ve ever witnessed to the legendary premiere of L’age d’or (t930), except that the outraged spectators weren’t members of the high bourgeoisie but French hippies, so incensed by the non-narrative rigors of Snow’s film that they hooted and whistled all the way through; someone even waved a brassiere in front of the projector, an act greeted by wild applause. Consequently, I had to see most other American experimental films of this era during my trips to New York, most often at Anthology Film Archives, and I wound up missing all the early films of Ernie Gehr.

Paris flashback #2: During the five days I spend in Paris prior to my five days in Rotterdam, I see Noël Burch, who plans to give a lecture in Rotterdam shortly after I return to the U.S., a paper he’s currently working on – “The Sadeian Aesthetic: A Critical View” — and he gives me an early draft for my comments. The lecture grew out of an invitation to participate in ‘The Cruel Machine’, a series of films, videos and lectures programmed by Gertjan Zuilhof that Noël has serious misgivings about. Zuilhof mainly defines cinematic cruelty in relation to three films he describes as classics — Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960), Gualtiero Jacopetti’s Mondo Cane (1963) and Frans Zwattjes’ Pentimento (1980) — and Burch’s intervention seeks to critique “what I see as the social relationship central to high modernism, between the demiurgical, megalomanic, ultimately sadistic power of the Great Creative Mind and the stoic masochism of the ordinary devotee, flattered to share the austere tastes of an elite”.(1) A radical and to my mind utopian, even quixotic attempt to reconcile his masochistic sexuality with his Marxist politics and his quarrels with French modernism, Noël’s project is clearly mined with booby traps — especially because Sadeian and masochistic aesthetics as Noël defines them are so intertwined with the issues of being French and being American that inform his own autobiography –- but I also can’t help but see it as a noble and heroic undertaking. (Coincidentally, the modernist elevation of Sade has recently been interrogated in the U.S. — extensively and to my mind persuasively — by Roger Shattuck in Forbidden Knowledge: From Prometheus to Pornography [2]. and it’s a pity Noël hasn’t yet been exposed to this book.) Whatever its pitfalls, it’s so ambitious and instructive an undertaking that I find myself carrying out a silent dialogue with it every day I’m in Rotterdam.

On the one hand, I feel that Burch’s total rejection of his own earlier formalist writing and his current defense of mainstream masochism (i.e., Josef von Sternberg) over what he views as the Sadeian aesthetic of high modernist experimental filmmaking (Brakhage, Gehr, Snow, etc.) mainly bypass concerns that address my own experience. But on the other hand, no one else is really attempting to reconcile his sexuality, his sexual politics and his aesthetics in quite so concerted a fashion, and whether he intends this or not, I once again find myself stimulated by his arguments as a kind of meta-science-fiction.

Today Noël feels he has to reject his own Praxis du cinéma as an elitist validation of everything Sadeian/modernist aesthetics stand for. Yet for me the book was valuable in the 70s (when it was translated as Theory of Film Practice [4]) not as any sort of political or social model but as a guide to strains in filmmaking and formal analysis that I was still learning about; for me, it formed an unlikely but essential dialectic with Andrew Sarris’s The American Cinema as a sort of catalogue of what I should be seeing and how I should be seeing it. My point is that as a scavenger and bricoleur, I have a natural tendency as a spectator to pervert the aesthetic and political programs of others, and I believe all spectators (Burch included) do this on some level. Consciously or unconsciously, we all compulsively reinvent films and aesthetic programs in the direction of our own desires, making honest and practical criticism all the more difficult.

***

As I discovered in college, one can take virtually any line in English poetry follow it with a particular line from T. S. Eliot — ‘Like a patient etherized upon a table’ — and confidently expect the two lines to fit together and even produce a coherent meaning. What is it about this line from “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” that makes it so versatile and user-friendly? I suspect it’s the fact that the etherized patient is none other than ourselves, modernist spectators, committed to following our own divided consciousness wherever it might lead us, which is almost always away from society.

But exceptions to this rule are well worth noting. Included in “The Cruel Machine” and seen by me on video, Stephen Dwoskin’s personal essay Pain Is . . . (1997) — a blend of autobiography, investigation and philosophical reflection — is by far the most powerful film that I see in this program, because it lucidly brings sadism and masochism (among other related topics) into a public arena as something to be examined, not merely experienced or mythologized. Made by an experimental filmmaker who has spent most of his life in a wheelchair because of-his polio, it has the most complex and nuanced treatment of pain of any film I know because, as Zuilhof notes in the festival catalogue, it does not distinguish between wanted and unwanted pain. The film opens with a point-of-view shot taken from a wheelchair moving through hospital corridors until broad daylight bleaches out the image, and over the last part of this voyage, Dwoskin’s off-screen voice begins to ask questions about pain, only a few of which are answered. (‘Is it possible to make an image for pain? . . .When you rub your finger on wood, you feel the wood. If you get a splinter, you feel your finger. That’s how pain works. It moves from outside to inside.’)

The film is full of close-ups of people discussing, experiencing, administering and representing pain of different kinds — aggressive and extreme close-ups that often justify the term used to describe them, ‘chokers’. Yet most of the words used to describe the pain in question are relatively detached and dispassionate, distancing one’s responses. In the film’s most remarkable sequence, Dwoskin films in close-up a dominatrix while she’s beating him with a strap, work she clearly enjoys, and then while he calmly interviews her after the session about her work. It’s an approach that somehow evokes both Brecht and Montaigne, and for me it provides a precise dialectical (and modernist) response to Burch’s attack on the Sadeian aesthetic by moving from inside to outside, Is this achievement enhanced or contr6dictcd by the fact that I’m seeing it on video, alone with my own sexuality and my own phantoms? Not having the benefit of a comparison with how it plays before a full audience, I can only speculate about the answer.

I attend the first program in the Gehr retrospective at the Lantaren on Thursday evening — Shift (1972-4), This Side of Paradise (1991) and Side/Walk/Shuttle (1991), along with about twenty other spectators, most of them Dutch people in their twenties, and the response in this case seems fairly bemused and cool; the first question asked Gehr by someone after the films is, “Are you some kind of 16mm fetishist?” Though I’m taken especially by the camera movements and structural rigors of Side/Walk/Shuttle, this is a solitary experience more than a collective one, in striking contrast to what I shared with hundreds of enrapt spectators — again, most of them Dutch people in their twenties -– at part of a video program called “City Sounds” at the Pathé a few hours earlier.

Having smoked a joint before the previous afternoon program, it’s theoretically possible that I could have been idealizing the good vibes at “City Sounds”, but I don’t think so. For one thing, the first work in the program, Jason Spingarn-Koff ‘s >>Abducted<< (1996) — a twelve-minute video from Germany, shot in Berlin, Providence and New York — begins in the explicit context of television: one sees a TV monitor over pulsing signals (including some in red and green) located in a panel below, and on the TV screen are silent, faded images of city landscapes. For another, the presence of music (percussive ‘industrial’ music credited to DJ Fresh Blend) places this in a separate universe from Gehr’s work. A full black and white video image fills the screen after the initial television context is established, and a seductive rudimentary narrative establishes itself: a female figure recalling Maya Deren gets up from a bed in a sunny loft and walks over to a window, then subsequently is seen moving through color-stenciled background images of a city while intertitles in German periodically tell us things about her journey: “A television tower stands high above the city”, ‘Did something happen here? Perhaps something terrible”, “At the Reich air ministry?”, ”Here stood a Jewish department store”. In effect, the video is recounting a voyage through a dark and unfathomable history that proceeds from the turn of the century to contemporary Berlin, meanwhile resurrecting memories of silent German cinema and the Holocaust that appear like half-remembered dreams, and the overall experience is so bewitching that I wind up seeing > >Abducted< < a second time on video at the Central a few days later.

Does this imply that the more solitary pleasures of Gehr’s explorations are now a thing of the past? Maybe so, but only for some spectators. When I return to the Lantaren for another Gehr program on Saturday night, this one consisting exclusively of silent films — Serene Velocity (1970), Table (1976), Mirage (1981) and Eureka (1974) — on this occasion there are at least sixty spectators in the auditorium, and virtually no one leaves. So it appears that some sort of education of the audience has taken place between Thursday and Saturday — an induction into a way of seeing and reflecting upon film images that can only grow with experience.

On the other hand, I doubt that an audience for Gehr films can ever achieve the collective rapport that I witness and share when I see > > Abducted < < for the first time, and I suspect that the use of music has a great deal to do with it. I experience Some of the same difference when I see Blight (1996), a video from London made by John Smith in collaboration with the composer Jocelyn Pook – a fascinating work that is simultaneously a documentary about the construction of the M2 Link Road in East London, which provoked a protracted campaign by local residents to protect their homes from demolition, and a treatment of some of these residents’ impromptu speech as the basis for a kind of musique concrete — the various voices accompanied by piano chords and beautifully orchestrated with the editing, so that I’m inspired to write in my notebook, ‘Like Frank Zappa, only better”

The question is, does the collective audience rapport provoked by Blight become translated into any kind of social engagement with the video’s subject? Here I become less confident, if only because collective social engagement — including the kind that rejected Michael Snow at the Olympia in 1971, as well as more positive forms of involvement — is much harder to find nowadays at the cinema than other kinds of collective emotion. This is surely in part because the utopian vision of the 60s is no longer available to a contemporary audience; there is too much skepticism about culture and the media, about the plausible gains of revolutionary consciousness, for such a possibility to be considered.

This becomes even more apparent when I attend a David Shea concert on Friday night in which he accompanies Johan Grimonprez’s feature-length video Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y (1997) on a synthesizer, below and directly in front of the screen. The video is a compilation of found footage of TV news broadcasts about terrorist acts (mainly hijackings of planes over the past thirty years) as well as cartoons, commercials and instructional films –- a post-modernist celebration of banality, incoherence and fear that reminds me of the similar compilations of Craig Baldwin. It might be argued that Grimonprez escapes the nihilistic framework of Baldwin by including passages of intelligent and suggestive commentary about terrorism from two novels by Don Delillo, White Noise and Mao II, but I consider this distinction mainly academic because Grimonprez chooses to import someone else’s commentary rather than offer any commentary of his own. Similarly, Shea’s accompaniment incorporates echoes of the scores of Alphaville (1965) and various Hong Kong films – more post-modernist appropriations that can’t always distinguish between text and commentary.

From a 60s’ political perspective, this is all highly dubious and clearly “irresponsible”. Yet I also find myself sympathizing with and even partially sharing the quasi-euphoric collective experience being offered by this combination of elements, an experience that combines the pleasures of surprise and adventure with political defeatism in a distinctively 90s manner. To find pleasure in such sources of pain as “urban renewal” and terrorism certainly requires a considerable amount of alienation, but it also has to be admitted that this alienation is already produced by the culture and not by the contemplative pleasures derived from reflecting about it, Even if such a perversion of social consciousness represents an ideological impasse, it fully acknowledges that state of affairs, and the pleasure it provides derives in part from that acknowledgment. Is this like the bitter pleasure of a trapped animal rattling the bars of its cage? If it is, maybe the bars first have to be rattled before they can be broken or removed.

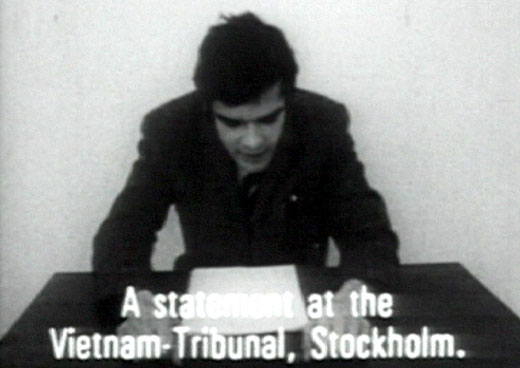

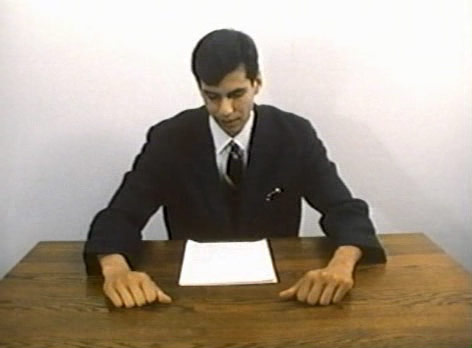

On two successive days in the vidéothèque, Sunday and Monday, I see two half-hour American films made in the Midwest, Jill Godmilow’s What Farocki Taught (1998) and Elisabeth Subrin’s Shulie (1997), both of them precise remakes of political documentaries made in the 60s: Godmilow’s film remakes a black and white German documentary made by Harun Farocki in 1969 about the production and effects of napalm, Inextinguishable Fire, in color and in English; and Subrin’s film remakes a 1967 documentary made by Jerry Blumenthal, Sheppard Ferguson, James Leahy and Alan Rettig about Shulamith Firestone, the future author of The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (1970) — a book I still recall as powerful — when she was a student at the Chicago Art Institute. What Farocki Taught represents itself as a non-fiction film; Shulie concludes with the title, “This is a work of fiction.” (6) Both 60s’ films are works of desperate inquiry, and the same can be said of both 90s’ films, for all their marked differences in subject and style.

I have to confess that I prefer Subrin’s Shulie to the film it remakes, if only because the complex historical pathos produced by her efforts yields far more information about the 90s than the original film could possibly tell us about the 60s, then or now. However, I prefer Inextinguishable Fire to What Farocki Thought, because the political motivations of the former are more direct and lucid. My preferences have very little to do with the technical skill or resourcefulness of either Subrin or Godmilow, but they have a great deal to do with assessing the value of a political work in its own time.

With some justice, conventional wisdom has it that the 60s were a much freer time than today, so there’s a certain boldness in Subrin focusing on a moment in that period when feminist consciousness was still struggling to be defined. The paradox is that even historical hindsight isn’t enough to give an actress thirty years later the kind of emotional urgency Firestone conveyed in the original film through her own shyness and confusion; Kim Soss, the actress playing Shulie, projects the kind of contemporary coolness we tend to identify as normal. Yet it’s only through this juxtaposition that we begin to see the petrifying fear that describes our present moment — the kind of fear that makes the very notion of a remake seem like a logical response.

On Monday, during my final afternoon at the festival, I attend a screening at the Pathé of the Taiwanese feature Blue Moon (1997). Scripted and directed by Ko I-cheng – a member of the Taiwanese New Wave who is best known as an actor outside of Taiwan, particularly for his roles in Edward Yang films — this feature consists of five twenty-minute reels designed to be shown in a separate order each time, so that 120 different versions are possible. All five reels feature more or less the same characters and settings – including, among others, a young woman, a writer, a film producer and a restaurant owner, all living in Taipei and belonging to the same circle of friends and acquaintances – and in each reel, the woman is involved with a separate man. One can therefore construct a continuous narrative by positing some reels as flashbacks, as flash-forwards, or else as events that exist in a parallel universe,

Apart from this unique construction -– Ko explains after the screening that he wrote all five parts simultaneously, on different colored sheets of paper – Blue Moon is conventional, even “commercial” narrative feature, and one of my American colleagues who saw the film earlier dismisses it for precisely that reason as banal and disappointing. But for me it’s fascinating for precisely the same reason: because it demands the creative participation of the viewer at the same time that it pretends to satisfy one’s conventional expectations. And there are other beautiful rewards as well: for example, I’ve always hoped one day to see a feature that unconventionally includes its credits somewhere in the middle, and this particular configuration of Blue Moon fulfills that dream by showing the film producer look at a credits sequence in a projection room at the end of the second reel – a credits sequence that I feel sure provides the credits of Blue Moon. More conventionally, the very first reel of this screening explains the significance of the film’s title.

In short, the possibilities of satisfying some of the spectator’s desires and thwarting others are endless, and I completely agree with the film-maker Jackie Raynal, whom I attend this screening with, when she says afterwards that she immediately wants to see the film again, with the reels in a different order. To be sure, not all of the multiple narratives’ mysteries can be solved in this fashion, but some fresh clues will undoubtedly emerge, just as additional mysteries will be added. In some ways, it’s like the experience of sampling at a film festival condensed into a single feature, obliging each spectator to make his or her own synthesis out of the disparate yet interconnected pieces. Does this make it a political as well as experimental film? Insofar as it addresses and seeks to change the relation of the spectator to the cinematic apparatus, it can’t be anything else.

End Notes

1. Noël Burch, ‘The Sadeian Aesthetic: A Critical View’ in Dave Beech and John Roberts (eds), The Philistine Controversy (London/New York: Verso, 2002), p. 179.

2. Roger Shattuck, Forbidden Knowledge: From Prometheus to Pornography (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996).

3. Noël Burch, Theory of Film Practice (London: Secker & Warburg, 1971).

4. Andrew Sarris, The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968 (New York: Dutton, 1968).

5. Shulamith Firestone, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (New York: Morrow, 1970).

6. This title was subsequently removed.