Published in Screen Slate on October 13, 2021. — J.R.

Two book launch events take place in London, both on October 23: The Liberated Film Club vs. Important Books (or, Manifestos Read by Children) at LUX at 3:00pm, and a screening of György Fehér’s Twilight (1990) at Close-Up Film Centre at 8:15pm.

On October 23, 2021 Tenement Press will release The Liberated Film Club, a collection of transcripts, texts, etc., related to a screening series of the same name that took place at London’s Close-Up Film Centre 2016–2020.

Two book launch events take place in London, both on October 23: The Liberated Film Club vs. Important Books (or, Manifestos Read by Children) at LUX at 3:00pm, and a screening of György Fehér’s Twilight (1990) at Close-Up Film Centre at 8:15pm.

Screen Slate invited critic Jonathan Rosenbaum to review the book.

I’m a sucker for genre-defying “What is it?” books, and this one is further enhanced as well as complicated by chronicling a London film club that’s no less eccentric and transgressive in its refusal to stand still and behave reasonably or even (on occasion) coherently. This is plainly an anarchist book designed for insiders, and I’m an outsider—or maybe one could say that this is an anarchist book designed for outsiders, and we’re all outsiders interested in redefining what an alleged “inside” might consist of. (“Can it be,” Harold Rosenberg once wrote, “that everybody is looking for a way to fit in? If so, doesn’t that imply that nobody fits?”) Even though I’m a former London-based civil servant (having worked in the British Film Institute’s Editorial Department in 1974–1977), and even though, thanks to mischief-maker Stanley Schinter, I was privileged to appear in two post-Liberated Film Club programs at London’s Close-Up Film Centre in early 2020, I’m still a Chicago-based writer who wasn’t around for any of the fun and games chronicled or evoked here, and indeed, this book is the very first thing I’ve ever heard about the Club. The cast of characters includes four people whom I know and admire (Laura Mulvey, Chris Petit, Schtinter, Astra Taylor) and several others who are mostly unfamiliar names, though they’re often referred to here by others as stalwart, chummy standbys.

Furthermore, I cannot tell a lie. I agreed to review a book called The Liberated Film Club while suffering from entropion in my left eye and eyelid—a condition in which the eyelid is rolled inward against the eyeball so that, prior to corrective surgery, I can only read most texts with a magnifying glass. (July 26, 2022: Thanks to successful if gradual recovery, I can now read most texts without this assistance.) Moreover, the only text of this book available to me is a PDF file on my laptop screen, and I’ve been having an easier time watching films (or, rather, digital reproductions of films) at this venue than reading books. So my entropion disrupts ordinary reading at least as much as The Liberated Film Club disrupted ordinary filmgoing and film discourse, and by the same token, it has liberated me from some of the usual protocols and requirements of book reviewing. If I followed the same requirements of people invited to introduce the unannounced and unknown films of The Liberated Film Club, I would review this book without reading a word of it. But because this whole anarchist undertaking is about breaking certain rules and habits, I’ve broken such a rule by reading some but not all of the book, piecemeal and somewhat haphazardly—a wholly lifelike and life-sized encounter that is worthless as a theoretical gesture.

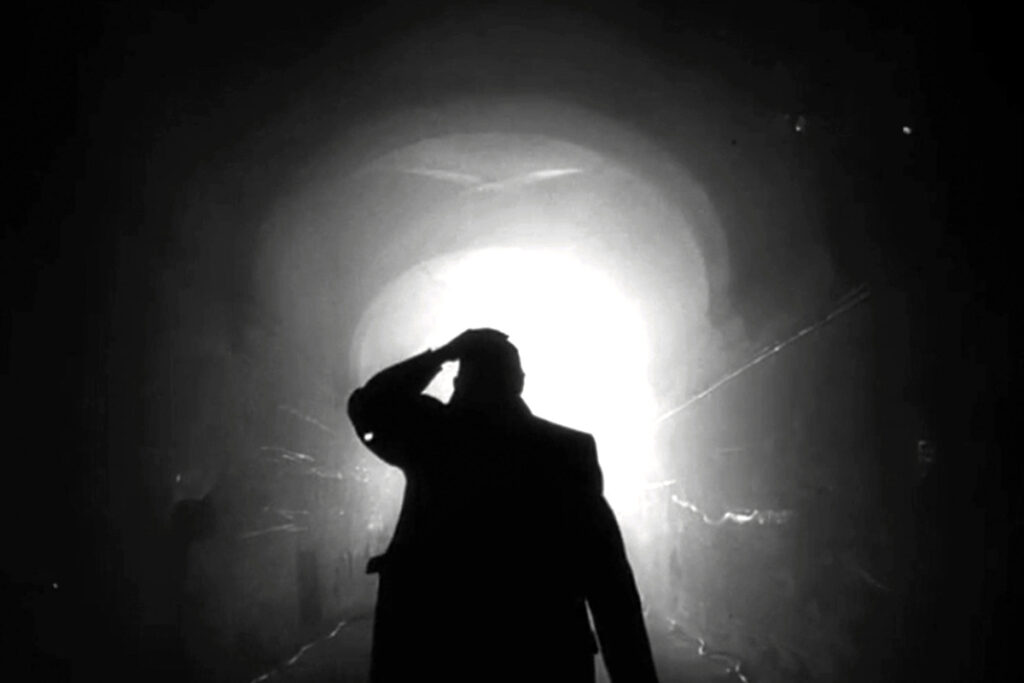

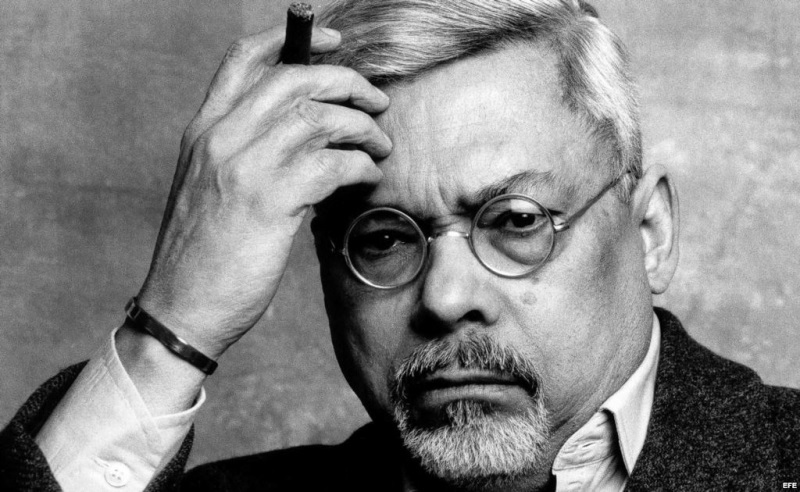

I’m reminded of a legendary lecture on Orson Welles announced and delivered by the great G. Cabrera Infante at the Cuban Cinematheque, which he reportedly founded or cofounded at some point during the pre-revolutionary mid-1950s, while he was still a film critic for Carteles calling himself G. Cain. This was also before he went on to write his remarkable novel Three Trapped Tigers (1967), which celebrates and commemorates Havana during its Batista period.

It is announced that the lecture will be given in two parts, on successive weeks. An audience gathers for Part One; Cabrera Infante steps up to the podium and delivers it: “Orson Welles is a whale.” Then he steps down.

General consternation and outrage. Due to the uproar and its spreading fallout, an even greater number of people turn up the following week. The curtains part. Carbrera Infante is nowhere to be seen or found, but in his place there is a poster running across the entire length of the stage that says: “Orson Welles is a butterfly.”

Whether or not this story is apocryphal—and a Cuban friend has insisted it’s the unvarnished truth—it actually says more about Welles than a good many academic critical studies, not only for its metaphorical acuity but for its adroit mixture of presence and absence that replicates Welles’s ways of being and sometimes not being in the world. It’s especially relevant to his F for Fake (1973), which can be described simultaneously as his most public gesture and his most private one. As a longtime believer in mimetic criticism, I applaud Cabrera Infante’s thoughtful provocation as well as those of Stanley Schtinter, which are in some ways equally imaginative as well as presumptuous.

As Matilda Munro’s description of The Liberated Film Club has it, “Schtinter answered what he saw to be a serious need for an open void for audiences to jump into.” And as Jean-Luc Godard once observed in a different context, reviewing Jacques Becker’s Montparnasse 19 (1958), “He who leaps into the void owes no explanation to those who watch.” Maybe Godard was poetically or metaphysically right, but the very existence of both this book and this review refutes his premise by offering a veritable slew of explanations, no two of which are alike. The merit of Schtinter’s plan for neither the film’s introducer nor its audience to know in advance what film would be shown is that creative energies are not only created but necessitated by this sort of madness, and the ensuing creations that are liberated—spoken, written, discussed, or merely thought—are necessarily varied. Astra Taylor’s employment of the Exquisite Corpse game with her audience may have produced a lot of dead meat, as Munro suggests, but the carving up of it must have been pretty lively.