From Cineaste, Fall 1998. –J.R.

Speaking About Godard

by Kaja Silverman and Harun Farocki; foreword by Constance Penley. New York/London: New York University Press, 1998. 245 pp., illus. Hardcover: $55.00, Paperback: $17.95.

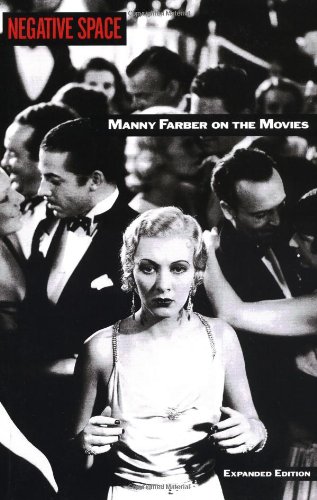

Negative Space: Manny Farber at the Movies (expanded edition)

by Manny Farber; preface by Robert Walsh. New York: Da Capo Press, 1998. Paperback: $15.95.

Kaja Silverman and Harun Farocki’s dialogues about eight features by Jean-Luc Godard, stretching from Vivre sa vie (1962) to Nouvelle vague (1990), is a book I’ve been awaiting ever since coming across its sixth and seventh chapters, on Numéro deux (1975) and Passion (1981), in issues of the journals Camera Obscura and Discourse, respectively. The two best critical studies I’ve encountered anywhere of these difficult, neglected masterworks, they manage to account for a great deal of what’s going on in them, metaphorically, ideologically, and intellectually, and the graceful division of labor between the two critics as they proceed through the films — roughly speaking, a dialectical exchange between Freud (Silverman) and Marx (Farocki) — makes the process of their exploration all the more illuminating. Silverman, a film theorist who teaches at Berkeley, and Farocki, a German essayistic filmmaker with over seventy films to his credit, are both primarily concerned with what these two films mean, and they attack this question with a great deal of lucidity and rigor.

Unfortunately, these turn out to be their best chapters, perhaps because challenging films of this kind turn out to be ideally suited to the authors’ methodology. And on balance, Speaking about Godard has more to say about Godard’s thought than about his esthetics. (In this respect, it has a dialectical relationship to the extended treatment of Godard in Gilberto Perez’s invaluable The Material Ghost, which significantly fails to mention either Numéro deux or Passion.) I was immediately put off by a howler on the first page, when Silverman remarks of Vivre sa vie, “The film ends with a two-minute long close-up of [Nana’s] corpse, which has been brutally reduced to a few seconds in the American version.” Even if one accepts the premise that our final glimpse of Anna Karina is a close-up, my version of the film on video, coming from a Japanese laserdisc, ends just as abruptly as what Silverman calls “the American version,” and so do the versions I’ve seen in Europe.

Three pages later, describing the film’s opening scene — a dialogue in a cafe between Nana and Paul (André S. Labarthe) — Farocki says, “The exchange at the counter represents a conversation of perhaps twenty minutes, but it summarizes the events of three or four years.” The entire scene, in fact, lasts less than seven minutes, over five of them spent at the counter, and if by “represents” Farocki means “condenses” — implying an abbreviation of a longer scene that we don’t see — then surely more of an explanation is required.

The other films selected for analysis are Contempt, Alphaville, Weekend, and Le gai savoir — a good representative choice — and the usual method is to move through each film from beginning to end, which makes this book especially suitable for classroom use. As Constance Penley puts it in her foreword, when Farocki and Silverman speak about Godard, “they are concerned above all else with the performance of the text, with the unfolding, over time, of that complex and never-to-be-repeated structure of inimitable sounds and images that comprises each of his films.”

Penley is also insightful about the particular talents and investments that Farocki and Silverman bring to their work. But I’m less convinced when she asserts that “this book is by, for, and about unabashed cinephilia,” because a comprehensive grasp of film history and the history of film criticism — both of which play substantial roles in the meanings of these eight films — is what I find most lacking in this book. As astute as the authors often are about Lacan and Althusser, Descartes and Rimbaud, and various paintings, they don’t have anything substantial to say about Godard’s complex and singular flair for critically citing and cross-referencing other films in his images: the roles played by, say, German expressionist cinema in the lighting and iconography of Alphaville (which they link exclusively to film noir), or Fritz Lang’s overhead angles in the framing of certain shots in Contempt. For all of Farocki’s sensitivity as a filmmaker to the implications of cinematography, lighting, and editing, he still has a tendency to favor political discourses over images.

Still, there’s much to be said for the advantages proposed by this book for lively conversation over monologues, especially when it comes to a mercurial figure like Godard. And much the same can be said for the eight additional pieces included in the invaluable expanded edition of Manny Farber’s Negative Space, seven of which are cosigned by Patricia Patterson, despite the fact that only the last of these takes the explicit form of a dialogue — a remarkable forty-four-page interview with Farber and Patterson by Richard Thompson, originally published in 1977, that for me represents perhaps the most exciting piece of freewheeling film criticism ever published in English.

In its original 1971 edition, Negative Space was already a sturdy classic, representing a quarter of a century of Farber’s pioneering, radical exploration of film art that took in everything from Warner Bros. cartoons in 1943 to Godard, Michael Snow, and Luis Buñuel in the late Sixties — with remarkable studies of such figures as Preston Sturges, Val Lewton, Howard Hawks, and various actors in between. Seeing this art as part of a much larger world is central to Farber’s gift. The energy of the writing is often as pungent as Sixties Godard, and what matters most about it isn’t the accuracy of every detail but the aptness of the overall drift. A characteristic sentence from Farber’s 1957 “Hard-Sell Cinema,” and one that happens not to be about movies at all: “Without the human involvement and probing of Parker’s sax-playing — the pain-wracked attack, as well as the playfulness and sudden spurts of wildly facetious slang — Getz turns the baritone sax into a thing that can be easily mastered, like a typewriter.” The fact that Stan Getz actually played tenor, not baritone, pales beside the insight into two jazz styles and what it implies, and the fact that this observation gets sandwiched between remarks about Twelve Angry Men and Larry Rivers’s painting without causing any bumps in the argument is probably even more important.

As Robert Walsh points out in his helpful new preface, Patterson — an artist and teacher like Farber — “began collaborating informally” with Farber on his essays in 1966, originally without credit, and “had an ever stronger hand” in the pieces written from the late Sixties onwards. Though Farber already wrote in a polyphonic style to begin with, Patterson’s contributions only added to the layered density of the prose and the positions and approaches taken in these later forays. The fireworks that resulted have never been seen before or since — taking in subjects as diverse as Raoul Walsh (in the best piece ever written about him) and Godard, Werner Herzog and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Nicolas Roeg and Marguerite Duras, Taxi Driver and Jeanne Dielman, the team of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, and the Westerns of Anthony Mann.

As in Farber’s earlier solo efforts, what emerged as definitive in their efforts wasn’t the goal of total explication — the effect achieved in the Silverman-Farocki readings of Numéro deux and Passion — but the articulation of their collective voice and the model it offered of total engagement with their subjects. In its dizzying swerves from approval to abuse, from long-shot survey to close-up observation, their dissection of Taxi Driver as both art and as social act is an awesome act of scrutiny, but it never fosters the illusion of being exhaustive.

Developed concurrently with this couple’s careers as painters and teachers, these sparkling essays are a good deal more concerned with pedagogical and political matters than Farber’s previous criticism, yet they never succumb to either the theoretical jargon or the anti-art positions that were being developed in most branches of academic film study around the same time. In contrast to the desire to settle issues and evacuate mysteries that informs most university prose then and now, Farber and Patterson are interested mainly in raising questions and then following them down whatever garden paths these questions suggest, taking in all the ensuing scenery. Though twenty-one years have passed since the last of these pieces was written, there isn’t a more up-to-date book of American film criticism in print.