From Cineaste, Vol. XXIX, No. 4, September 2004. This is also reprinted in my collection, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. — J.R.

Although I suspect many would dispute this characterization, I think the period we’re now living through may well be the first in which scholars have finally figured out a good way of teaching film history. And significantly, this discovery isn’t necessarily coming out of academic film study, even if a few academics are making major contributions to it.

I’m speaking, of course, about the didactic materials accompanying the rerelease of some classic films on DVD. Three examples that I believe illustrate my thesis especially well are (1) the various commentaries or audiovisual essays offered by Yuri Tsivian on DVD editions of Mad Love: The Films of Evgeni Bauer (Milestone), Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (Kino International/BFI), and Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible (Criterion); (2) the commentaries offered by David Kalat on Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (Blackhawk Films) and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (Criterion); and (3) the various documentary materials offered on “The Chaplin Collection,” a twelve-box set issued jointly by MK2 and Warners and put together with the full resources and cooperation of the Charles Chaplin estate. These DVDs include not just all of Chaplin’s features apart from his last, The Countess from Hong Kong (presumably missing due to rights issues), but historical introductions written and read aloud by Chaplin biographer David Robinson, newsreels, home movies, outtakes, production photos, relevant shorts by Chaplin and others, and 26-minute episodes in a brand-new series called “Chaplin Today” devoted to historically placing each of these features as well as interviewing a contemporary filmmaker for his or her impressions about it.

The Chaplin Collection’s editor, Serge Toubiana, a former editor of Cahiers du Cinéma, has commissioned, among others, many writers from that magazine, past and present, to direct the various chapters of “Chaplin Today,” each of whom has drawn materials from the plentiful Chaplin archives as well as other sources. Thus we get Alain Bergala filming (and interviewing) Abbas Kiarostami on The Kid (1921), Mathias Ledoux filming Liv Ullmann on A Woman of Paris (1923), Serge Le Péron filming Idrissa Oeudraogo on The Gold Rush (1925), François Ede filming Emir Kusturica on The Circus (1928), Serge Bromberg filming animator Peter Lord on City Lights (1931), Philippe Truffault filming Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne on Modern Times (1936), Bernard Eisenschitz filming Claude Chabrol on Monsieur Verdoux (1947), Edgardo Cozarinsky filming Bernardo Bertolucci on Limelight (1952), and Jérôme de Missolz filming Jim Jarmusch on A King In New York (1957).

The remaining DVDs, which break with this pattern, are devoted to Richard Schickel’s recent documentary Charlie: The Life and Art of Charles Chaplin, The Chaplin Revue (consisting of A Dog’s Life, Shoulder Arms, Sunnyside, A Day’s Pleasure, The Idle Class, Pay Day, and The Pilgrim), and The Great Dictator (1940). The latter, however, gives us an excellent 55-minute documentary by Kevin Brownlow and Michael Kloft called The Tramp and the Dictator (a virtual object lesson in how to pursue the subject of Chaplin and Hitler honestly and responsibly — in striking contrast to the capriciousness of the comparison between Orson Welles and William Randolph Hearst in the 1995 Oscar-nominated The Battle Over Citizen Kane), 25 minutes of Sydney Chaplin’s color “home movie” footage of the shooting of Dictator, a seven-minute outtake from Sunnyside (1919) showing the Tramp as a barber, and even a three-minute clip from Monsieur Verdoux.

Although Chaplin is still the closest thing we have to a universally recognized, understood, and appreciated artist, the degree to which he needs to be reintroduced to contemporary filmgoers — and reintroduced from an international rather than American perspective — can’t be underestimated. This is surely why the second volume of The Chaplin Collection garnered only a B+ from Entertainment Weekly (along with the headline, “Film directors laud the Little Tramp’s brand of camp”) — in contrast to, say, Scenes from a Marriage (A), George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (A), and 21 Grams (A-) in the same issue, making it tie with the “complete first session” of episodes from The Flintstones and the “20th anniversary edition” of Splash, both of which also got B pluses. After all, we’re meant to conclude, Chaplin is spectacularly uneven: “City Lights is a classic of sentimental comedy because it gets the mix of sentiment and comedy just right. The Kid and The Circus do not. They are bathetic, and A Woman of Paris plays like bad Balzac.” And if you’re still wondering why “bad” Balzac and Chaplin are deemed inferior to “good” Bergman, Romero, and González Iñárritu, this presumably has something to do with how far back in history we have to go. (Frankly I have my own demurrals about The Circus, in spite of the brilliance found in certain sequences. But any dismissal that can bracket it indiscriminately with The Kid can’t be very attentive to either.)

In other words, one can’t even begin to grasp Chaplin’s importance without processing sizable chunks of the 20th century, and from a universal rather than a local perspective. For this reason, I can’t say that I have a lot of patience for colleagues who still presume that it’s possible to compare Chaplin and Buster Keaton in any normal fashion, either as slapstick performers or as directors. As Gilbert Adair once pointed out years ago, Chaplin doesn’t simply belong to the history of cinema; he belongs to history. And for me the main problem with trying to compare him to Keaton is that such an act implicitly denies that history, which the Chaplin Collection is dedicated to explicating as clearly as possible.

Even less useful than the Chaplin versus Keaton debate is the kind of contemporary dismissal of Chaplin that writes him off as a sentimentalist, a relic of the 19th century, an insufferable egotist, or a technical or intellectual primitive. Not because one can’t go back to certain facets of his life and work and find some evidence to support any or all of these charges, but because doing so ultimately entails a reductive reading that excludes too many other things that matter at least as much. I’m far more sympathetic to the hyperbole of Jean-Marie Straub’s provocative defense of Chaplin as the greatest of all film editors — made most recently and most cogently in Pedro Costa’s beautiful 2001 documentary Où gît votre sourire enfoui?, which documents the activity and conversation of Straub and Danièle Huillet while editing one of the versions of their Sicilia! Straub’s justification for this extravagant claim is ingenious: because Chaplin knew precisely when a gesture begins and when it ends, he knew precisely when to cut. As an observation this is far more indicative of a close and prolonged engagement with the work than any of the curt and cavalier dismissals. And maybe because Straub is himself a lot more (radically) traditional and conservative than he’s generally cracked up to be, part of what he’s saying is that in spite of everything, Chaplin remains our contemporary — someone we can still learn from and converse with without condescension or apology.

Similarly, I would argue that those who reject A King in New York because they find Chaplin’s ideas in it too obvious, simplistic, or bitter are likely to be overlooking the fact that he places many of his own most cherished leftist and anti-nationalist sentiments in the mouth of an obnoxiously self-righteous and hectoring brat (Michael Chaplin) who often won’t let Chaplin’s title king get in a word edgewise when he holds forth. This implies a dialectical as well as self-critical side to Chaplin — not to mention a certain intellectual depth — that few commentators are likely to concede about the man. As with Marilyn Monroe — a charismatic figure whose parallels with Chaplin run deeper than one might initially suppose — an apparent compulsion to dismiss his intellect is so deeply ingrained and takes so many (unthinking) forms, including the premise that the lack of intelligence is self-evident, that one starts wondering about all the ideological determinations that hold this cherished premise in place. Even when faced with certain anomalies — such as Chaplin’s admiration for Ivan the Terrible (which runs parallel to Monroe’s interest in The Brothers Karamazov) — the usual impulse is to patronize the star with condescending “tolerance” for his or her pretensions and to try to rationalize this information out of existence.

The frequent charges waged against Chaplin’s “old-fashioned” technique often seem predicated on an assumption of naïveté and/or vanity on his part. A typical anecdote that supposedly illustrates this: an assistant points out to Chaplin that some of the rails laid out for a tracking shot are visible in a camera setup, and he replies, “It doesn’t matter. Whenever I’m onscreen, the public won’t be looking at anything else.”

I have no idea whether or not this story is apocryphal, but in the final analysis it doesn’t matter. Whether or not Chaplin said such a thing, there are far too many instances in his oeuvre demonstrating the accuracy of such a remark to make either his innocence or his egotism the central point of the story. My favorite example, in fact, is probably the most famous sequence in any Chaplin film, and presumably therefore one of the most closely studied in all of cinema: the closing moments of City Lights, when alternating close-ups of the Tramp and the flower girl, who has recently had her sight restored, record her dawning realization that he is her benefactor, the one who paid for her operation — as well as his own dual realization that she can now see and that she knows who he is. “She recognizes who he must be by his shy, confident, shining joy as he comes silently toward her,” James Agee memorably wrote in “Comedy’s Greatest Era”. “And he recognizes himself, for the first time, through the terrible changes in her face. The camera just exchanges a few quiet close-ups of the emotions which shift and intensify in each face. It is enough to shrivel the heart to see, and it is the greatest piece of acting and the highest moment in movies.”

I wouldn’t dream of disputing any of this. But how many viewers have noticed that the alternating close-ups described by Agee are flagrantly mismatched? Viewed from behind, the Tramp grasps one of the flower girl’s flowers against his leg; viewed from the front, he holds the same flower in the same hand against his mouth and cheek, and this discontinuity of angle/reverse-angle even gets repeated along with the same camera setups. If we stop to wonder why almost no one seems to notice this error, I would dispute that any lapse in Chaplin’s perfectionism is to blame. Indeed, it’s questionable whether it even qualifies as a lapse when the emotion and ambiguity of these shots are all that finally register and matter. It’s a sequence, in short, that should be shown and described to every film student who has ever believed that eyeline matches count for very much outside of routine filmmaking.

To take another approach, consider just the realm of raw experience imparted by Chaplin’s films. Has there ever been another artist — not just in the history of cinema, but maybe in the history of art — who has had more to say, and in such vivid detail, about what it means to be poor? Conceivably Dickens, another artist often reproached for sentimentality, might be a contender in these sweepstakes, but surely no other figure in the 20th century. And because there is arguably no other figure in the world during Chaplin’s heyday who was more widely known and loved — not even a politician like his arch-enemy Hitler, much less another artist — discussing him as if he were just another writer-director or actor ultimately means short-changing that world and that history.

The only other figure in the arts who strikes me as being even remotely comparable to Chaplin — with lots of emphasis on “remotely” — is Louis Armstrong, and only in a few characteristics: coming from theabsolute bottom of society and assuming a kind of ethical elegance and nobility as well as a kind of charisma and joy informed by both wit and low comedy that were peculiarly his own; redefining the parameters of an art that was new and largely associated with America while becoming a seasoned and universally recognized world traveler and a kind of statesman.

***

If all this sounds like idolatry, it could be argued that I have plenty of company. It’s hard to think of a populist mainstream figure who was more beloved by avant-garde artists on both sides of the Atlantic during the teens, 20s, and 30s. So is it any wonder that Chaplin has suffered from an almost continuous critical backlash in the 70-odd years since then? Part of this undoubtedly comes from the ideological disturbance of attending to such a massively popular figure who was effectively forced into exile from the U.S. after the public started to turn sour on him. To understand how this radical change of heart came about entails part of the substantial history lesson offered by The Chaplin Collection, along with a prolonged and detailed look at the changes that took place in his filmmaking and in both the evolving identity of the Tramp and the subsequent parts played by Chaplin. (A comparable history lesson might undertake to explain how the persistence of Jerry Lewis as a love object in this country throughout the 50s could eventually mutate into a denial as well as an implied horror that such an infatuation could ever have existed.)

In Felice Zenoni’s mainly unexceptional recent Swiss TV documentary about Chaplin in Switzerland, Charlie Chaplin: The Forgotten Years (2003), there’s an unforgettably humanizing nugget recounted by Chaplin’s daughter Geraldine about his response to discovering that his invitation to accept an honorary Oscar in the U.S. in 1972 came with a visa that only allowed him to remain in the country for a couple of weeks. Though one would expect him to have been indignant, we discover that he was in fact delighted to learn he was still regarded as being so frightening and challenging a figure to American authorities, 20 years after leaving the country. And if that sounds spiteful, it’s no more so than the Tramp himself often is when faced with various enemies.

To understand the changes in Chaplin’s filmmaking in any depth, we’re still pretty far from having the sort of critical perspective that’s needed. If we turn to the Chaplin biographies — either those in print or those on film and video (including the disappointing feature-length documentary by Schickel) — we often get continuations of the same ideological roadblocks, many of which consist of rationalizing or otherwise ratifying the critical and commercial rejections of Monsieur Verdoux and A King in New York and all that these imply.

I assume it’s partly this kind of continuing backlash that held back the U.S. release of eight of the dozen features in the Warner/MK2 Chaplin box set for about half a year after they came out in Europe. The first four were The Gold Rush, Modern Times, The Great Dictator, and Limelight, and it’s not surprising that the more controversial and less commercial Chaplin titles — Verdoux, King, A Woman of Paris — were saved for the second batch.

The packaging of the PAL and NTSC versions are different in other respects. European customers also received illustrated booklets in all dozen packages and in some cases more informative details on the boxes themselves. Furthermore, they received A Woman of Paris and A King in New York separately, while these two features are indecorously shoehorned together in the American set, presumably for no better reason than the fact that they’re both regarded as awkward encumbrances, like two unwanted children. (The first is silent and doesn’t star Chaplin, the second unabashedly anti-American; and both were box office flops.)

The Masters of Cinema web site [no longer operative in the same form in 2009] maintains that “the R2 UK set from Warner/MK2 and the French MK2 set are a magnificent achievement” but that “unfortunately, the USA R1 set is a lazy PAL [to] NTSC transfer with ghosting — extremely disappointing.” The PAL version placed third in their 2003 poll for the “DVD of the year” — after two very impressive Criterion releases, By Brakhage: An Anthology and Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story, in the first two slots — and the ideological as well as technical differences are underlined:

“Back in 2001, the Chaplin estate wisely sought the skills of MK2 in France (after seeing their superb Truffaut boxset) and asked them to conjure up a Chaplin set. Two years later, we have this dreamlike set, with perfect extras. If this set had been put together in the USA we’d have extras consisting of Leonard Maltin chatting with Robin Williams, Billy Crystal and Adam Sandler. Okay, maybe Sandler would’ve been interesting, but what we get from MK2 raises the bar as high as it can go — Abbas Kiarostami, the Dardenne Bros, Liv Ullmann, Claude Chabrol, Jim Jarmusch, Emir Kusturica, and Bernardo Bertolucci contribute, separately, to the documentary for the film with which they have a personal affinity. It’s refreshing to encounter a huge release like this with a distinctly European flavor, one that hasn’t been dumbed down to the lowest common denominator to maximize dollarage. Hats off to the Chaplin estate and MK2 for doing Charlie very proud. Hats firmly left in place for Warners USA.”

With all due respect to this conscientious web site, whom I generally agree with and find indispensable, a couple of demurrals are in order. Having had an opportunity to compare the French PAL version of The Kid with the American NTSC version back to back on my multiregional DVD player and tristandard monitor, the differences in sound and image are undetectable, at least by my eyes and ears. (Nevertheless, there are plenty of other reasons for preferring the French PAL versions, including the fact that the interviews with directors that aren’t in English can be seen there with English subtitles, whereas the same interviews on NTSC are saddled with English voiceovers that don’t allow us to hear all of the original voices.) And while I heartily agree on principle with most of the filmmakers selected to comment on Chaplin, candor compels me to note that for all his brilliance as a filmmaker, Kiarostami seldom has anything of interest to say about his colleagues, and has very little to offer on this occasion, either about Chaplin in general or The Kid in particular. (Significantly, when he recently decided to subtitle his Five — a collection of five short and rather beautiful digital videos concentrating on relatively uneventful patches of the natural world found on a beach — Five Takes Dedicated to Yasujiro Ozu, this was a clever way of alerting his audience to what they should and shouldn’t expect, even though the actual resemblance of these videos to anything by Ozu is highly questionable.)

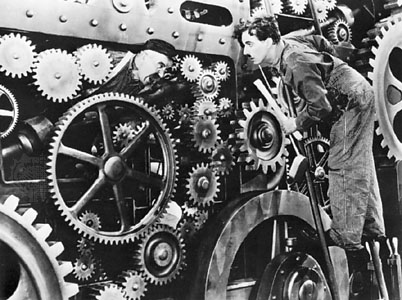

On the other hand, the various comments offered by the Dardenne brothers about Modern Times comprise the most insightful criticism about the film I’ve encountered anywhere. Starting with the observation that the famous early shot of the Tramp moving literally like a cog through the factory machinery is an image that recalls a film running through a projector, they proceed to speculate why, in relation to an entire commercial cinema predicated on success stories, the Chaplin Tramp essentially remains a tramp — even though this time he’s identified in the credits as a factory worker. They also discuss the importance of hunger in his work (“Food is everything in his films”), the degree to which the film serves as a documentary on the period, and how the women in the film “aren’t very nice” until we get to Paulette Goddard.

With a similar commonsensical bent, Jarmusch on A King in New York speaks about how the title city becomes “representational” of “America as an empire,” money, and thievery, with a great deal of prescience about what America would become over the next several decades (and an apt observation that the film’s depiction of “rock and roll” is in fact a phony commercialized version of that music — not simply a misperception of it, as some commentators would have it), how Dawn Addams’ eerie eye contact with the camera while taking a bath anticipates her activity as a TV huckster, how the film’s overall technique is wholly subsumed to the storytelling, and how the film’s tragic ending completely avoids sentimentality. More generally, what makes Jarmusch a good commentator on the film isn’t just his own status as a political maverick but his special feeling for Chaplin’s independence: “He’s maybe the first truly independent master of cinema, because he has control over everything in his films.” In a way, this is a variation on Roberto Rossellini’s celebrated defense of A King in New York — “It’s the film of a free man” — and it highlights the degree to which Chaplin’s absolute independence had aesthetic as well as ideological consequences. (Indeed, part of what continues to make the film indispensable historically is the degree to which it deals with all the major issues missing from the Hollywood features of the same period — including Tashlin’s Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, its only true satiric competitor.)

In other parts of the Truffault documentary on Modern Times, we see newsreel footage of Chaplin meeting Gandhi in London, detailed production information on Modern Times, an exploration of the issues involving Chaplin’s development of the Tramp in this film, a more general discussion of Chaplin’s evolving relationship to sound — including a newsreel clip of him briefly recording his voice on film for the first time during a 1931 visit to Vienna, a clip of the jabbering speeches we hear in the opening scene of dialogue in City Lights, the original plans for spoken dialogue in Modern Times, and a fascinating montage of three of its slapstick sequences, including the famous dance on roller skates, shown successively at 18 and then 24 frames per second. One fascinating piece of information that we don’t get here — but which is imparted in the Schickel documentary –is the fact that the famous malfunctioning feeding machine was secretly operated manually by Chaplin himself under the table it was on. (Similarly, there’s a fascinating piece of information imparted by the 1975 Oxford Companion to Film that’s lamentably missing from The Tramp and the Dictator: that The Great Dictator was originally banned in Chicago, reportedly to avoid offending the sizable German population there.)

De Missolz’s “Chaplin Today” episode on A King in New York begins with the detail in the film that feels most contemporary today — the fingerprinting of King Shahdov upon his arrival in the U.S. — and proceeds from there to such matters as newsreel footage about Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, Chaplin’s move to Switzerland in 1952, United Artists’ refusal to distribute Chaplin’s film (and the fact that the film was shortened by ten minutes when it finally opened in the U.S. 15 years later — although we aren’t told what was removed), and the film’s rapid shoot (only ten weeks) in London and its editing in Paris. But perhaps the most touching sections concern Michael Chaplin — starting with an anecdote about the consternation he caused at the age of seven in his father’s office in Switzerland when he entered one day in a homesick mood singing “God Bless America”. Elsewhere we see him watching his own spouting of political oratory in the film and then speaking about the whole experience in French, implying that the experience of acting was the time when he was able to be closest to his workaholic father. A particularly poignant “bonus” in this already poignant interview is the background music used — Chaplin singing his heretofore unheard lyrics to a song he wrote that is used in the film as Michael’s theme.

The highlights in Eisenschitz’s Verdoux documentary include Chabrol’s celebration of the audacity of the film’s unapologetic atheism and of the fact that all the women Verdoux kills “are ugly and unbearable,” thereby putting the audience as much as possible on Verdoux’s side, and his stressing of the fact that all of Chaplin’s work is about survival. Chabrol also offers a fascinating extended commentary on a shot showing professional tango dancers in a restaurant, the sort of detail that few other critics would even notice. We also get material about Chaplin’s public defense of Hanns Eisler (with a fascinating clip of Eisler’s angry HUAC testimony, and an account of Chaplin’s unsuccessful effort to gain Picasso’s support against Eisler’s threatened deportation), details involving Hays office objections to the script, a generous sampling of production storyboards as well as some rushes, interesting analyses of the characters played by Martha Raye (as an American shrew transferred to a French context) and Marilyn Nash (as a figure who alters Verdoux’s destiny), and some interesting remarks about the film’s final shot (including the fact that Chaplin shot it before anything else in the film), by Chabrol as well as by André Bazin.

To show his own contempt for Chaplin’s FBI file, Cozarinsky on the Limelight DVD has his offscreen narrator quote copiously from it before we see a pair of hands (actually Cozarinsky’s) tear the document into shreds and toss it into a river. The high point of Bernardo Bertolucci’s commentary about the film is his observation that when the young dancer (Claire Bloom) declares her undying love for Calvero, “She is lying, and deep inside she knows she is. He [Calvero] knows Terry is lying, and we know he knows. It’s all sort of staged.” (This shows the limitation of Pauline Kael’s 1953 hatchet job — her first published film review, recently reprinted in Artforum — which assumes a complete absence of ambiguity or irony about this matter.) By contrast, I would call the low point of Bertolucci’s commentary his labored effort to persuade us that when Calvero dies, the sheet draped over his body is supposed to make us think of a movie screen. Far more interesting on this DVD is a troubling scene with Calvero conversing with a former colleague with one arm that Chaplin decided to cut from the film.

Among the other treasures to be found in this set, I would cite in particular, apropos of The Gold Rush — and apart from the fact that we get both the 1925 original and the 1942 retooling with Chaplin’s offscreen narration — Ouedraogo’s hypothesis that the Tramp’s crazed image of a gigantic chicken is so large because it “becomes proportionate” to the size of his hunger (which leads logically to both a quote from art historian Élie Faure and an earlier hunger gag from A Dog’s Life); images of children in Ouedraogo’s village watching Chaplin for the first time in a video of The Gold Rush; a clip of Fatty Arbuckle in the 1917 The Rough House, which shows us the source of the dance with the rolls, and portions of an audio interview with Mary Pickford about the source of Chaplin’s interest in the Klondike.

And apropos of A Woman of Paris, I would cite in particular the sensitivity of Ullmann’s observations, eleven minutes of outtakes, ten minutes of footage documenting Paris in the 20s, and an extraordinary film document of 1926: a thirty-three-minute version of Camille by Ralph Barton in which the cast of celebrity cameos includes not only Chaplin, but also, to cite less than a third of the remaining lineup, Sherwood Anderson, Ethel Barrymore, Richard Barthelmess, Paul Claudel, Clarence Darrow, Theodore Dreiser, John Emerson, Dorothy Gish, Sacha Guitry, Rex Ingram, Sinclair Lewis, Anita Loos, H.L. Mencken, George Jean Nathan, Max Reinhardt, and Paul Robeson.

To keep track of all these appearances, a program listing who plays whom is obviously essential. This information is part of the booklet included in the French PAL version but not something that anyone has bothered to make available on the American NTSC version. If there’s any lesson to be gleaned from this, this is surely that the same team of French people who lavished so much care on this box set obviously cared more about making it user-friendly than the American team devoted to distributing it. And this difference in concern for historical value suggests another key lesson, for both the present and the foreseeable future: that one of the crucial qualifications of an educated and cosmopolitan DVD watcher is owning a multiregional player.

— Cineaste, Vol. XXIX, No. 4, September 2004