From the March 1, 1996 issue of the Chicago Reader. —J.R.

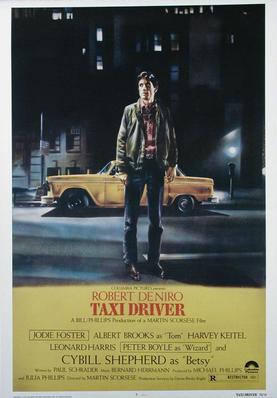

Taxi Driver

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by Paul Schrader

With Robert De Niro, Jodie Foster, Harvey Keitel, Cybill Shepherd, Albert Brooks, Peter Boyle, Leonard Harris, Steven Prince, and Martin Scorsese.

Perhaps the most formally ravishing — as well as the most morally and ideologically problematic — film ever directed by Martin Scorsese, the 1976 Taxi Driver remains a disturbing landmark for the kind of voluptuous doublethink it helped ratify and extend in American movies. Of all Scorsese’s movies, Taxi Driver — being screened this week at the Music Box in a 20th-anniversary “restoration” that’s in stereo for the first time — is for me the most seductive, though I wouldn’t call it either his best film (I’d choose the underrated The King of Comedy) or his most gut-wrenching (I’d pick the overrated Raging Bull). Most of the glamorous depictions of hell on earth and odes to stoical despair about a postapocalyptic civilization found in monuments to capitalist-urban squalor, including Blade Runner and Seven, can be traced back to Taxi Driver, and if it continues to exert an enormous claim on our imagination, this is surely because we continue to live in its vengeful, puritanical fantasies — as well as with the dire consequences of those fantasies.

Properly speaking, Taxi Driver has four auteurs, whose agendas are distinct in some specifics and overlapping in others: director Scorsese, writer Paul Schrader, actor Robert De Niro, and composer Bernard Herrmann. I’ll start with Herrmann, in part because he’s been the most neglected of the four, in part because he’s the sturdiest link to the commercial filmmaking of the three decades preceding 1976. Herrmann is best known for his work for Orson Welles (Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons), Alfred Hitchcock (eight films, including The Wrong Man, Vertigo, North by Northwest, and Psycho), François Truffaut (Fahrenheit 451 and The Bride Wore Black), and Brian De Palma (Sisters and Obsession). He was so adamant about his aesthetic biases that he single-handedly succeeded in persuading De Palma to eliminate the entire third act from Schrader’s script for Obsession — a radical abbreviation that was Herrmann’s prerequisite for scoring the film. His last two major scores, for Obsession and Taxi Driver, give the films so much formal, emotional, and thematic shape that the usual rule of music serving as accompaniment often seems reversed, and the images, dialogue, and sound effects seem to accompany the scores.

Herrmann died at age 64 in Los Angeles on Christmas Eve 1975, only hours after he conducted the Taxi Driver score, which I would cite as the most richly realized of all his late compositions for movies. The one time I met him was in a London editing studio only 16 days before he died; though quite ill, he was deciding whether to score a French film on the basis of a few rushes at a screening I’d helped set up for a filmmaker friend. Herrmann’s method of deciding involved a fascinating interface of aesthetics and business: he dictated a hypothetical instrumentation for a score to his secretary, added musicians’ fees and French studio costs, and then decided whether it was worth his while to continue.

This interface of art and business is fundamental to the achievement of his Taxi Driver score, which helps disguise or at least rationalize the film’s ideological confusions, all of which circulate around the psychotic hero, Travis Bickle (De Niro). It assigns them an emotional purity that nothing else in the movie expresses — an emotional purity that coalesces around two contrasting themes that are endlessly reiterated and juxtaposed. For the purposes of this discussion I’ll call these the “heaven” and “hell” themes. The first is associated with Bickle’s feelings toward two supposedly angelic female characters — a professional political campaigner he’s attracted to, Betsy (Cybill Shepherd), who’s working for a presidential hopeful named Palatine, and a 12-year-old street hooker he wants to save, Iris (Jodie Foster). (Bickle fails to develop any sort of relationship with Betsy, after making the cardinal error of taking her to a porn movie on their first date, but he improbably winds up “saving” Iris by killing her pimp — played by Harvey Keitel — and a couple of his associates.) The hell theme, at once more brooding and more bombastic, smoldering with repressed rage, is associated with the contaminated vision of Manhattan that informs Bickle’s tortured, puritanical reveries from first frame to last.

The heaven theme is a lush, jazzy ballad of romantic yearning performed by alto saxophonist Ronnie Lang that suggests a much older and more upscale cultural tradition of big-city aspiration than anything else in the movie (except perhaps a few shots outside the Saint Regis Hotel) — a tradition closer to Herrmann’s generation than to that of Scorsese, Schrader, and De Niro, who were all born in the 1940s. This lyrical “penthouse” lament suggests the dreaminess of Gershwin or Porter rather than any musical tradition directly tied to Bickle — a former marine in his mid-20s who opts for driving a taxi as an expression of his terminal loneliness, insomnia, and spiritual and social isolation. The benefits of using such a musical idiom to legitimize, sentimentalize, and romanticize — in short, to glamorize — Bickle’s madonna-and-whore notions about women are incalculable. (To be fair, the bridge midway through this 32-bar standard introduces subtle doubts by becoming oddly polytonal — the muted trumpet and muted trombone playing in a different key than the accompanying strings and piano, conveying something of Bickle’s dissociated state of mind. But the final eight bars revert to the chordal comfort of the beginning, landing the audience squarely on its feet.)

The hell theme combines flurries of rat-a-tat snare-drum percussion like military drumming (almost subliminally suggesting Bickle’s former experiences in Vietnam and his various disciplinary measures of “self-improvement,” ranging from push-ups to target practice) and discordant, growling sustained low notes played mainly by brass instruments, which are somewhat more evocative of other Herrmann scores (e.g., the power theme in Citizen Kane). The richly orchestrated darkness of this second theme also becomes associated with images of black males, violence, crime, street hustlers of various kinds, infernal gusts of steam (from gratings and manholes) and water (from fire hydrants), pollution, and the stench of New York in the summer — an overloaded package that, combined with a worshipful treatment of firearms (lighted and filmed in one pivotal sequence as if they were religious icons), validates the Calvinist hysteria, xenophobia, racism, and trigger-happy savagery of Bickle more effectively than anything he ever says or does, by treating them as the subject of monumental art.

Much as Herrmann’s brilliance is used mainly against the film’s ostensibly responsible social agenda — an agenda that labels Bickle a dangerous psycho rather than a Hollywood hero and that regards his implausible triumph at the end of the picture ironically — De Niro’s remarkable playing of the character brings a charisma to the part that frequently contradicts or at least complicates the script’s construction of him as a disturbed and disturbing creep. As Patricia Patterson and Manny Farber noted in “The Power & the Gory,” the best critical study of Taxi Driver I’ve read, published in the May-June 1976 Film Comment: “The fact is that, unlike the unrelentingly presented worm in Dostoyevsky’s Underground Man, this handsome hackie is set up as lean and independent, an appealing innocent. The extent of his sexism and racism is hedged. While Travis stares at a night world of black pimps and whores, all the racial slurs come from fellow whites.” Perhaps not quite all — Bickle at one point announces that he’ll drive anyone anywhere, even “spooks” — but very nearly.

This form of dishonesty is of course ascribable to the script rather than to De Niro, but it’s endemic in the star system, which thrives on the seeming resolution of such contradictions. How can Marilyn Monroe’s Lorelei Lee in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes be simultaneously knuckleheaded and some sort of genius? Because the capacity of stars, unlike ordinary mortals, to be contradictory things at once allows audiences to slide effortlessly over the contradiction. Perhaps it was this capacity that made De Niro’s Bickle — charismatic misogynist and psychopathic killing machine — a role model for John Hinckley when he attempted to assassinate Ronald Reagan (as Bickle almost tries to assassinate Palatine) to impress Jodie Foster (whom Bickle “saves” by slaughtering a number of Lower East Side lowlifes): not exactly a coherent project, but then again it’s part of the job and capacity of stars to exalt and give life to incoherent projects. (It would be interesting to know how aware Hinckley was of the intended irony of the final scene. Surely Hollywood’s capitalist genius at playing both ends against the middle extends to giving psychotic viewers exactly what their hearts desire.)

The point here isn’t to parcel out blame but to consider the role of De Niro’s creativity in fleshing out his character and the role of a star’s screen presence in permitting certain meanings to register. A few scenes in the film — notably Bickle’s meeting with Betsy in a coffee shop and his celebrated “You talkin’ to me?” monologue, delivered to a mirror — grew out of De Niro’s own improvisations. It’s worth adding that his background as a New Yorker (Scorsese and Herrmann are also New Yorkers) undoubtedly enhanced the verisimilitude of Schrader’s script.

It should be stressed that Schrader’s script — a grim, confused reflection of his strict upbringing as a Dutch Calvinist in Grand Rapids, Michigan; he was forbidden to see any movies before he was 17 — is a twisted self-portrait that sorely needs the realistic inflections and star power furnished by De Niro and the seductive fantasy elements conjured up by Herrmann (emotional) and Scorsese (visual). Without their contributions the story of Taxi Driver would be deficient in conviction and overall appeal, for a surprising number of details are implausible from the outset.

In the opening scene, for instance, when Bickle applies for a job as a taxi driver, his jokey, smiling response to the query “How’s your driving record?” is “Clean, real clean — like my conscience”; this provokes an extended tirade from his potential employer (beginning “You gonna break my chops?”) that seems unmotivated and unbelievable — except, perhaps, as an indication of Bickle’s status as a pariah. The fact that Bickle keeps a diary — one of the details of Bresson films that Schrader emulates — is necessary to the movie’s structure and to De Niro’s offscreen narration, but it’s never very plausible. (Schrader went to the trouble of using the diary of another would-be political assassin — Arthur Bremer, who attempted to kill George Wallace — as a model, but the cosmic differences between Bremer and a charming figure like De Niro are simply glided over.) And the fact that, as far as we can tell, Palatine is a political candidate without a program, without a discernible ideology — rather like the unseen Hal Phillips Walker in Robert Altman’s Nashville — may also fit Schrader’s conception, but it’s hardly a convincing profile.

We also have to consider that some crucial aspects of Schrader’s script were jettisoned at the outset. In the mid-70s he said, “Long ago Pauline Kael asked me why I wrote about this character, what it had to do with me. I said, ‘It is me without any brains.'” More recently, in the book Schrader on Schrader, he said, “At the time I wrote [the script] I was very enamored of guns, I was very suicidal, I was drinking heavily, I was obsessed with pornography in the way a lonely person is, and all those elements are upfront in the script. Obviously some aspects are heightened–the racism of the character, the sexism….In fact, in the draft of the script that I sold, at the end all the people he kills are black. [Scorsese and the producers] and everyone said, no, we just can’t do this, it’s an incitement to riot; but it was true to the character.”

One obvious consequence was that racist remarks were transferred to other white characters. (One of these characters is played by Scorsese himself — a lunatic passenger of Bickle’s who makes Bickle seem like a model of sanity, though it’s this customer’s ecstatic evocation of “what a .44 magnum” can do to a woman’s face and “pussy” that apparently inspires Bickle to buy the same handgun.) The transference of Bickle’s racism (via script changes) and the rationalizing of his sexism (via the romantic score) force these elements into the very poetics of the movie’s vision instead of leaving them as isolated elements in the psychosis of an individual character. This is where the uncommon talents of Scorsese come in — as an aesthetic catalyst.

For critic Robin Wood, writing in his 1986 book Hollywood From Vietnam to Reagan, the ultimate incoherence of Taxi Driver can be traced to “a relatively clear-cut conflict of auteurs,” though for him there are only two — the Catholic Scorsese and the Protestant Schrader. For Wood “The [political] position implicit in Paul Schrader’s work…can be quite simply characterized as quasi-Fascist,” especially if one factors in his scripts for other directors.

Wood cites “the putdown of unionization” (Blue Collar), “the putdown of feminism ‘in the Name of the Father'” (Old Boyfriends), “the denunciation of alternatives to the Family by defining them in terms of degeneracy and pornography” (Hardcore), “the implicit denigration of gays” (American Gigolo), and “the glorification of the dehumanized hero as efficient killing-machine (unambiguous in Rolling Thunder, confused — I believe by Scorsese’s presence as director — in Taxi Driver).” To this list one could add later examples, such as the exploitation of sexual disgust in Schrader’s remake of Cat People, the direct celebration of Japanese fascism in Mishima, the trashing of radical politics in Patty Hearst (which he directed but didn’t write), and, reportedly, the flip trivializing of Hollywood blacklisting in his recent made-for-cable Witch Hunt (which turns the anticommunist witch-hunts into events involving actual witches).

Of course, according to the world of infotainment and most film reviewing, Schrader’s films, Taxi Driver included, are devoid of politics (Hey, folks, they’re just good, clean “entertainment,” massacres and all). But it must be admitted that Schrader — an intellectual and a former film critic of some distinction — doesn’t appear to make this error himself. (There’s even a scene in Taxi Driver — one of many bull sessions among Bickle’s fellow cabbies — that can be said to make fun of homophobia: a driver earnestly insists that every time a gay couple in San Francisco splits up one partner is required by law to pay the other one alimony.)

I think one has to say that the politics of Taxi Driver are confused rather than fascistic in any ordinary sense — opportunistically confused, to be sure, but not the simple call to violence that inspired Dave Kehr to call the movie “a thinking man’s Death Wish.” Consider the self-deluding naivete of Schrader’s declaration in Film Comment 20 years ago: “The controversial nature of the film will stem, I think, from the fact that Travis cannot be tolerated. The film tries to make a hard distinction for many people to perceive: the difference between understanding someone and tolerating him. He is to be understood, but not tolerated. I believe in capital punishment: he should be killed.” Maybe he should; but Taxi Driver doesn’t convict Bickle or even place him on trial; after killing everyone in sight at a whorehouse, in a massacre clearly intended to make us think of My Lai, he’s declared a hero by everyone in the movie who’s still alive — even Iris’s father profusely thanks him in a letter that’s read offscreen. One wonders, if Bickle had been arrested instead of applauded would the movie be remembered today as a timeless classic? For surely part of its achievement is to impart lyricism, poetry, and warmth to sentiments usually associated with genocide, validating Bickle’s murderous rage as much as criticizing it. Within these terms, “irony” becomes a convenient escape clause for the filmmakers — though it’s highly doubtful that if Bickle himself saw Taxi Driver he’d be inclined to read the ending as anything but straight.

Here’s another quotation from Patterson and Farber: “Taxi Driver is always asserting the power of playing both sides of the boxoffice dollar: obeisance to the boxoffice provens, such as concluding on a ten-minute massacre, a sex motive, good-guys vs. bad-guys violence, and casting the obviously charismatic De Niro to play a psychotic, racist nobody….On the other coin side, it’s ravishing the auteur box of 60s best scenes, from Hitchcock’s reverse track down a staircase from the Frenzy brutality, through Godard’s handwriting gig flashed across the entire screen, to several Mike Snow inventions (the slow Wavelength zoom into a close look at the graphics pinned on a beaten plaster wall, and the reprise of double and triple exposures that ends Back and Forth)….Taxi Driver is actually a Tale of Two Cities: the old Hollywood and the new Paris of Bresson-Rivette-Godard.”

Early in the same essay Patterson and Farber note “the jamming of styles: Fritz Lang expressionism, Bresson’s distanced realism, and [Roger] Corman’s low-budget horrifics” before going on to note specific echoes of scenes from other sources: “De Niro’s cab almost collides with the two child-whores — just as Janet Leigh’s fearful Psycho thief nearly overruns the man from whom she’s stolen a bundle….When De Niro stares at his Alka Seltzer glass, there is a tiny sneak zoom into the bubbling water, which adds one more shot to Godard’s rapidly-spoken philosophizing in [Two or Three Things I Know About Her] in which the camera frames the coffee cup from above.” And Pauline Kael has described a scene where the camera moves away from Bickle on a pay phone to an empty hallway as “an Antonioni pirouette.”

These are of course only a few sources of the film. I’ve already mentioned Schrader’s well-advertised indebtedness to Bresson, especially Diary of a Country Priest and Pickpocket. Schrader has also said, “Before I sat down to write Taxi Driver, I reread Sartre’s Nausea, because I saw the script as an attempt to take the European existential hero…and put him in an American context. In so doing, you find that he becomes more ignorant, ignorant of the nature of his problem.” Schrader has also described in detail how many aspects of the plot are suggested by Ford’s The Searchers, with Bickle serving as an updated version of John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards and Keitel’s pimp standing in for Scar, the Comanche warrior who kidnaps Debbie (Natalie Wood).

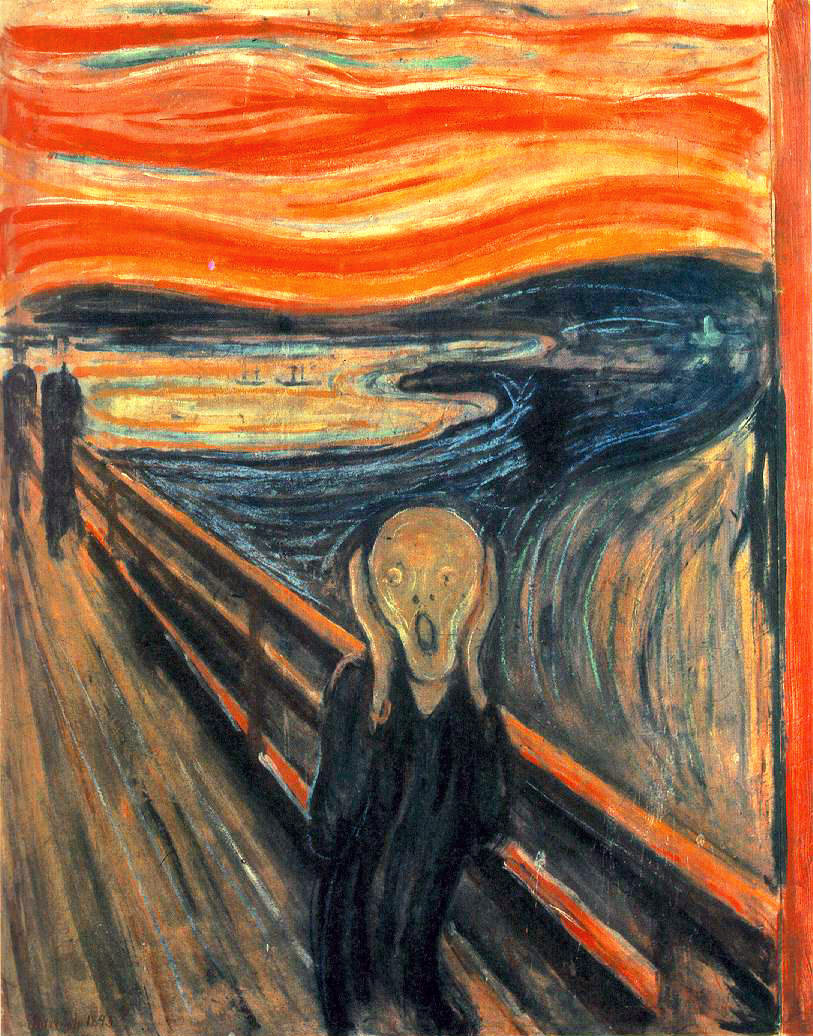

The incompatibility of these and other influences tends to be overcome by an overall homogenizing process that entails converting concepts from various social artists and thinkers into the private alienation of a single individual who turns out to be a charismatic mass murderer. If we recall some of De Niro’s goofy, demented grins in this picture, including those that provoke complicitous audience laughter, it wouldn’t be far-fetched to suggest that Taxi Driver takes a first step toward the mainstream gallows humor that will peak in Hannibal Lecter’s lewd winks in The Silence of the Lambs. More important, the power of expressionism to turn the torments of a single consciousness into a highly stylized landscape, a universe of pain, makes this movie an oddly ravishing treatment of mental unbalance: Edvard Munch meets George Gershwin.

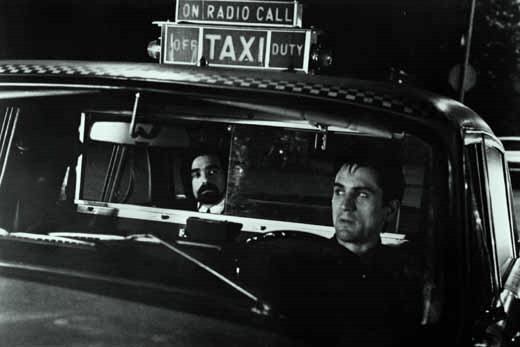

In short, thanks to what can only be termed the transformation of Taxi Driver‘s experimental and European elements into razzle-dazzle Hollywood effects, the spectator is invited to identify with a violently Calvinist, racist, sexist, and apocalyptic fantasy, complete with extended bloodbath, that’s given all the allure of glittering expressionist art and involves very few moral consequences for most members of the audience. Because the whole thing takes place inside one glamorous character’s head, the social ramifications are effectively rationalized to the point of nonexistence. It must be added that the gorgeous and extremely varied visual effects Scorsese and cinematographer Michael Chapman derive from a yellow cab moving through “hellish” New York traffic are as central to the film’s impact as its celebration of psychosis. Indeed, the two projects become intimately intertwined, impossible to distinguish.