My column for the December 2019 Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. — J.R.

En movimiento: Denial Incorporated and Cinematic Substitutes

Given how much we watch [TV] and what watching means, it’s inevitable, for those of us…who fancy ourselves voyeurs, to get the idea that these persons behind the glass — persons who are often the most colorful, attractive, animated, alive people in our daily experience — are also people who are oblivious to the fact that they are being watched. This illusion is toxic.

—David Foster Wallace

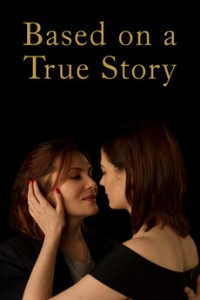

Insofar as “political correctness” often functions as a sad form of compensation for political powerlessness — so that one winds up eagerly penalizing a Roman Polanski or a Woody Allen for a real or imagined crime committed decades ago largely because one can’t find a way of getting rid of a Donald Trump in the present — the degree to which simple denial plays a role in governing one’s consumer choices needs to be recognized. What may be most significant about the flood of negative reviews in the U.S. given to Joker after both a slew of domestic mass shootings and the film winning a Golden Lion from Lucrecia Martel’s jury in Venice is how similar these reviews were to one another in both their phraseology and their arguments, comprising a herdlike form of collective expression that has to blame a movie for its frustration because it can’t (or at least won’t) blame the American gun lobby. For me, it was a creepy reminder of the way virtually all the American reviews of Oliver Stone’s Nixon (1995) used the word “Shakespearean” that was already shrewdly planted in the film’s pressbook to give a dubious tragic stature to its title hero (and by implication, to the public who voted for him). Similarly, Polanski and Allen are required to lose their potential audiences in 2019 not because of anything said or done in their recent films (such as Polanski’s arguably feminist Based on a True Story — which I was finally able to see recently only on a Spanish DVD) but because of stipulated sexual transgressions carried out respectively in 1977 and 1992. The degree to which Polanski’s and Allen’s guilt or innocence for such crimes continue to be passionately debated on social networks as if these celebrities were family members of the debaters and posters — posters who seem relatively indifferent to these filmmakers’ subsequent lives, activities, and films, as well as to the stipulated sex crimes of noncelebrities, even in 2019 — continues to astonish me. Like the “toxic illusion” cited by David Foster Wallace, this becomes a kind of fictional cinematic activity that doesn’t even need cinema to maintain its self-perpetuation; the solipsism of other forms of media, such as TV and the Internet, provides more than enough.