From the Chicago Reader (February 23, 2007). — J.R.

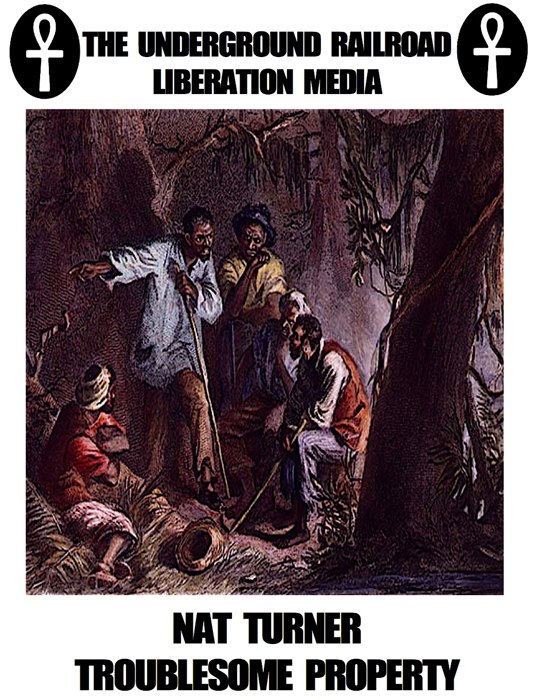

NAT TURNER: A TROUBLESOME PROPERTY ****

DIRECTED BY CHARLES BURNETT | WRITTEN BY BURNETT, FRANK CHRISTOPHER, AND KENNETH S. GREENBERG

WITH CARL LUMBLY, TOM NOWICKI, TOMMY HICKS, JAMES OPHER, WILLIAM STYRON, ERIC FONER, MARY KEMP DAVIS, OSSIE DAVIS, EKEWUEME MICHAEL THELWELL, AND BURNETT

THE ASTRONAUT FARMER *

DIRECTED BY MICHAEL POLISH | WRITTEN BY MARK AND MICHAEL POLISH

WITH BILLY BOB THORNTON, VIRGINIA MADSEN, BRUCE DERN, MAX THIERIOT, TIM BLAKE NELSON, BRUCE WILLIS, KIERSTEN WARREN, AND RICHARD EDSON

Very little is known about Nat Turner, the black slave in Virginia’s Southampton County who led a revolt by more than 50 other black slaves in August 1831. Over two days they slaughtered 57 white men, women, and children, and after the rebellion was suppressed, 60 to 80 slaves were summarily executed and mutilated. As one historian notes in Charles Burnett’s hour-long TV documentary, Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property (2003), screening Sunday at the DuSable Museum of African American History, we have precise information about Turner’s victims but know almost nothing about the slaughtered blacks.

Most of what’s known about Turner is based on his unverifiable “confession” to a white lawyer, Thomas Gray, before he was executed. “In the days before his execution he will agree to tell his story,” says Burnett’s narrator, Alfre Woodard, “but after his death, his words will become the property of others, as his body was during his life.” There have also been speculative accounts of his life by many historians and two major novelists, Harriet Beecher Stowe and William Styron. But Burnett refuses to privilege any single version of Turner, instead giving us two dozen talking heads, half of them black, and seven actors playing him.

This is what’s daring about Nat Turner — it doesn’t attempt to persuade us that any of these separate versions of Turner is true. It’s interested only in showing us where each came from. So the artificiality is deliberate when Tom Nowicki, playing Gray, turns to the camera to address us directly, while the great Carl Lumbly (who also played the title role in Nightjohn, another Burnett film about slavery) is visible as Turner in the jail cell behind him. Equally deliberate is the sequence in which actor Patrick Waller plays gently with a cat to illustrate the softening in Stowe’s fictional depiction of Turner. Viewers have to suspend judgment and understand that whatever conclusions they ultimately draw say more about them than about Turner.

As Burnett argues when he appears as one of the last of the film’s commentators, it’s possible to represent objectively positions one doesn’t hold. For instance, I happen to know from a conversation I had with him while he was working on the film that he rejects the view of Turner presented in Styron’s 1967 The Confessions of Nat Turner, but you wouldn’t know it given the way he adapts several scenes from the novel. Much more important to him is that in light of the very same facts many of the white commentators consider Turner a madman and many of the black ones consider him a hero. According to many white people in Southampton County in 1831, slaves there were “treated well,” which made Turner’s butchery doubly shocking to them. But the black commentators in the film tend to see slavery as the ultimate violence, making Turner’s efforts to overthrow it, no matter how bloody, a lesser evil.

Ultimately Burnett offers a remarkable gift: an intelligent sense of relativity. As Woodard’s narration puts it, “For a nation unable to come to terms with the legacy of slavery, Nat Turner remains a troublesome property.”

There’s no such respect for the viewer’s intelligence in The Astronaut Farmer, a piece of mythmaking stupidity opening commercially this week. It’s a fictional story, but the way it’s constructed suggests the filmmakers want us to believe it could be true — which a cameo by Jay Leno helps to reinforce.

The story concerns Charles Farmer (Billy Bob Thornton), a former NASA astronaut trainee in rural Texas who missed his chance to go into space when his father’s death forced him return to the family farm and pay off his bills. Years later he’s gone deep into debt building a full-scale rocket in his barn. He intends to launch it into orbit with himself inside, and his wife, Audie (Virginia Madsen), and kids back him to the hilt; his 15-year-old son is even prepping to serve as mission control. The scheme has made him a joke among his neighbors, though they do regard him with affection — he’s sometimes invited to address local schoolchildren in his space suit.

When Farmer’s banker refuses to add to his already huge loan, he petulantly throws a brick through the bank’s window like Tom Sawyer. In short, he’s the all-American dreamer (the ads say, “If we don’t have our dreams, we have nothing”), and the villains are the government suits who try to stop him. After an aborted launch almost kills him — a disaster that could have endangered other people as well — he refuses to give up. Then his supportive father-in-law (Bruce Dern) conveniently drops dead, leaving behind a fortune that allows him to pay off all his loans and rebuild the rocket. He takes off again, this time successfully.

There’s no scientific or humanist motive for Farmer’s dream — it’s strictly personal wish fulfillment. This is the basis of the mythical potency the movie aims for and asks us to endorse, a celebration of the same innocent lunacy that often gets us Americans into trouble — as it has, for instance, in Iraq. “Failure isn’t an option,” a mantra George Bush has offered as justification for escalating the war, could serve as Farmer’s motto. The value of his dream and its potential for destruction are irrelevant. Refusing to accept defeat is all that matters — at least if you’re the designated good guy.

The real Nat Turner, whoever he might have been, remains a troublesome property. But as long as we realize we’re the ones responsible for determining his historical meaning we can use him to fathom the legacy of slavery a little bit better. The fictional Charles Farmer, like his real-life counterparts, isn’t supposed to trouble us at all. But as long as we look at people like him with uncritical wonder we’ll have to take some responsibility for the threat they pose.