From the August 24, 1990 issue of the Chicago Reader. This is another film (see capsule review of Rita, Sue and Bob Too, posted earlier today) released on Blu-Ray by Twilight Time. For the record, I much prefer most or all of the features David Lynch has made since Wild at Heart, especially Inland Empire. — J.R.

WILD AT HEART

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by David Lynch

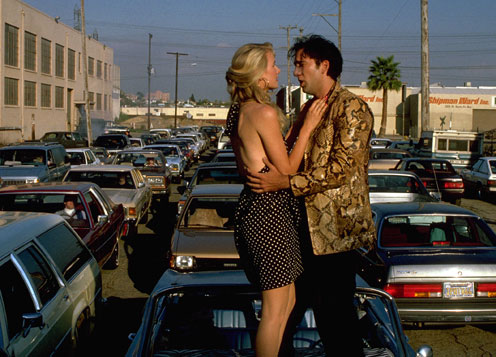

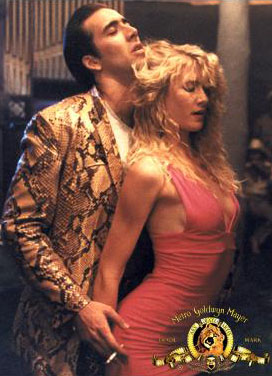

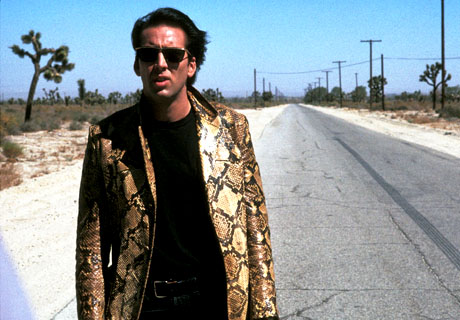

With Nicolas Cage, Laura Dern, Diane Ladd, Willem Dafoe, Isabella Rossellini, Harry Dean Stanton, and Crispin Glover.

The progressive coarsening of David Lynch’s talent over the 13 years since Eraserhead, combined with his equally steady rise in popularity, says a lot about the relationship of certain artists with their audiences. A painter-turned-filmmaker, Lynch started out with a highly developed sense of mood, texture, rhythm, and composition; a dark and rather private sense of humor; and a curious combination of awe, fear, fascination, and disgust in relation to sex, violence, industrial decay, and urban entrapment. He also appeared to have practically no storytelling ability at all, and in the case of Eraserhead, this deficiency was actually more of a boon than a handicap. Like certain experimental films, the movie simply took you somewhere and invited you to discover it for yourself. The minimal sense of story made it possible for you to take your own sweet time to find your bearings, and Lynch’s rich imagination guaranteed that there was more than enough to keep you busy.

When Lynch was hired by Mel Brooks to direct The Elephant Man (1980), he was able to incorporate a surprising amount of his own special qualities in someone else’s story, including a few effective nonnarrative interludes. There may have been something bogus and fatuous about the piety that Lynch brought to the material, but the script, by Christopher DeVore and Eric Bergren, was like a vehicle looking for an engine, and Lynch’s imagination — combined with the remarkable capabilities of Alan Splet, the sound man on Eraserhead — pretty much filled the bill. DeVore and Bergren also worked on the script of Dune (1984), albeit without a final credit, and Splet again did the sound design, but this time Lynch seemed hamstrung by the chore of adapting a complicated novel whose author (Frank Herbert) had veto power over the script, and he wound up with a top-heavy hodgepodge; in this case Lynch’s lack of narrative skills proved to be fatal.

He fared much better with his own material in Blue Velvet (1986), which was also his last film to date with Splet. Though the story is pretty murky, there is enough of a standard mystery plot — a young hero encountering dark goings-on in a small town — to provide the open-ended narrative pretexts for Lynch’s quirky inventions. The two-dimensionality of Lynch’s characters and his own fatuousness (already present in The Elephant Man and much more evident here) don’t work against him, because viewers are free to regard anything that doesn’t work — anything that isn’t psychologically or emotionally convincing — as camp; Lynch and the audience alike are protected from the problems that would arise if one ever had to take the shocker plot seriously. Without its irony, Blue Velvet resembles the lurid, confused imaginings of a sheltered 12-year-old boy wondering about sex between his parents; with the irony it can be taken as something more grown-up — the cynical scoffing of an adult at his own puerile notions.

Having arrived at this commercially important discovery, Lynch was all set to team up with Mark Frost (a writer who knew how to tell a story), pump up the camp (for use as a permanent escape clause), and produce Twin Peaks. If the loss of Splet was more injurious to Lynch’s art than the gain of Frost was beneficial, this counted for little beside the fact that Lynch was juicing up the prime-time TV serial — a form so sterile and primitive from the outset that any new spice and flavor was bound to seem like a major improvement, even if the only actual nourishment in sight was the same old meat and potatoes.

In the development of Lynch’s career so far, the thing that has pushed him further and further into strategies of shock (as opposed to moments of contemplation and drift, which are much more prevalent in his earlier work) has been the preferences of his audience, many critics included. The acceptance of these shock tactics as merely the “kicks” offered by an eccentric, surrealist imagination with no ideological significance of their own, coupled with understandable fears about recent inroads made by censors in limiting our choices, has discouraged many people from examining Lynch’s films too closely.

The pleasure of being shocked, which currently counts for a great deal in movies, is jeopardized if the implications of these shocks are looked at too closely. As George Orwell once observed while expressing his dislike for Salvador Dali, “Obscenity is a very difficult question to discuss honestly. People are too frightened either of seeming to be shocked or of seeming not to be shocked, to be able to define the relationship between art and morals”; this holds true for depictions of violence as well as sex. As a result of this difficulty, Lynch has been encouraged to intensify his shock effects, regardless of the aesthetic or ideological consequences this might have on the rest of his work.

The Frankenstein monster created by this attitude is fully visible in Wild at Heart, and looked at more than superficially, it’s a pretty appalling sight to behold. As story-telling, the movie is so inept that you may have to see the movie twice in order to get the story straight (though most of it proves to be childishly simple). As poetry, the movie is so preoccupied with sleaze and gratuitous lunatic walk-ons that it’s often about as subtle as Pink Flamingos. (I can think of only two memorable ‘Scope compositions — a diptych in a hotel room with Laura Dern standing beside a mirror and Nicolas Cage lying on a bed with a radio, and a shot involving Diane Ladd and three men, two of them crippled, in a hotel lobby — and the sound track is almost uniformly uninteresting.) At best, the movie is a string of disconnected effects and details, a silly camp odyssey that occasionally becomes a love story, a deck containing 52 wild cards, a lot of dirty talk, some fancy match cuts and dissolves, and a talented filmmaker continuously debasing himself any way he can for the sake of laughs and applause. When it works, and sometimes it does, it debases the audience as well as Lynch.

The plot of Wild at Heart comes from a novel of the same title by Barry Gifford, which was still in galleys when Lynch read it. Having read Gifford’s book twice before I saw the movie, I can at least say that Lynch’s material this time — apart from what he does with it — is a marked improvement over the red herring stews of Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks. Whatever its limitations as a self-conscious literary construct, Gifford’s novel is a well-written and often touching story about 20-year-old Lula and a parolee named Sailor, two young lovers on the run across a southern landscape, pursued by Lula’s neurotic mother Marietta and her writer boyfriend Johnnie Farragut. Broken up into 45 chapters over a mere 159 pages, the novel works on its own terms because of Gifford’s precise ear for southern speech (such as the way that Lula ends about half of her declarative sentences with a question mark), his feeling for the class differences between Lula and Sailor (which has a lot to do with Marietta’s distress), and his laconic feeling for southern gothic detail.

Gifford — who has published over a dozen volumes of poetry, coauthored biographies of Jack Kerouac and William Saroyan, and written books on baseball and film noir in addition to his fiction — organizes his vignettelike chapters in discrete poetic clusters, each one with an apposite title, which makes the book as a whole come across like a short-story or poetry collection as much as a novel. The characters’ heads are stuffed with anecdotes, memories, made-up stories, dreams, and the diverse flotsam of pop culture, and it is the mosaic of these small, interpolated narrative units as much as the story of Lula and Sailor that constitutes the novel’s overall effect.

The limiting and self-conscious side of the novel is its postmodernist reliance on noir references. I’m not thinking so much of the book’s dedication (“to the memory of Charles Willeford”) and opening epigram (“You need a man to go to hell with” — Tuesday Weld) as I am of the fact that Gifford’s imagination, unlike his mentor Willeford’s, seems determined at times more by other noir novels and movies than by life. Lynch, who appears to know little about noir as a genre, has sensibly jettisoned all of Gifford’s obvious references; not so sensibly, he has retained most of the less obvious ones that are built into the plot. And even less sensibly — given the plot he has to work with — he has substituted for Gifford’s obvious noir references his own extended references to Elvis Presley (in relation to Sailor) and the movie of The Wizard of Oz (mainly, but not exclusively, in relation to Lula), and used them as camp touchstones that not only facetiously comment on the plot, but, in the film’s concluding sequence, become part of it. Moreover, while he has tried to retain some of the novel’s mosaic effect, largely with his own inventions, his attempts to unify the diverse narrative clusters with visual motifs (e.g., lots of fire imagery) and frenetic crosscutting are willful and laborious, more like hiccups than like poetry.

These are not, to be sure, Lynch’s only changes. He invents a paranoid, juvenile subplot about an evil crime syndicate with endless tentacles, lorded over by a decadent tycoon named Mr. Reindeer. He turns Marietta from a pathetic neurotic into a demonic madwoman who crudely tries to seduce Sailor in a men’s toilet, then repeatedly tries to get him killed. Lynch also eliminates the character of her best friend (in many ways the best and most sensible character in the book), has hapless Johnnie Farragut (Harry Dean Stanton) tortured and murdered by the crime syndicate (with spooky rituals and weird sound effects that are like crude parodies of his best work with Splet), and adds a mystery about the death of Lula’s father to provide a flimsy additional motive for Marietta’s bloodlust. Finally, he tacks on a mock happy ending, fusing his campy Elvis and Oz references so they literally become the film’s denouement. His indifference to southern speech, class distinctions, and psychological nuance of any kind wreaks havoc everywhere, but is particularly injurious when it comes to Diane Ladd’s strident Marietta (Sailor even calls her white trash at one point, though it should be the other way around).

What is left of the original story after this thoroughgoing Lynching? Lula (Dern) and Sailor (Cage) are left, one might say, up to a point — Sailor periodically disappears to make way for Cage’s extended Elvis imitations, and Lula is decked out with so many bimbo cliches (like obsessive gum-chewing) that Dern’s effectiveness in spite of her slim part is something of a triumph. Some feeling for the couple and their passion persists despite Lynch’s attempts to ridicule their taste and spike their dialogue with clichés every chance he gets. (By contrast, their counterparts in the novel actually have brains.) As far as the rest of the southern characters are concerned, Lynch treats them with such scorn and contempt that southerners would be far more justified in raising a stink about this movie than various individuals and groups have been in protesting the fleeting Jewish stereotypes in Mo’ Better Blues.

Curiously, a lot of Gifford’s dialogue survives in reshuffled form, and ironically some reviewers have been quoting various lines of it — like Lula’s “The world is really wild at heart and weird on top” — as if they’re typical emanations of Lynch’s crazed genius. (Paradoxically, the funniest and most Lynchian character in the book — a 76-year-old crank obsessed with killing pigeons and who owned a business called “Rats With Wings” — doesn’t figure in the movie at all.)

I’m not claiming that Lynch has committed any crime per se in eviscerating Gifford’s book; much better books than this one have been destroyed in order to make worthwhile movies. What I object to, really, is the shameless way he has gone about this task. Perhaps the absence of anything resembling conscience can be regarded as some form of liberation, but it’s worth considering what exactly is being liberated. Take the case of Bob Ray Lemon, the character Sailor kills in a fight, which lands him in prison in the first place. All we know about him in the book is that Lula reflects at one point that “Society, such as it was . . . was certainly no worse off with Bob Ray Lemon eliminated from it,” and that Sailor attacked him in self-defense. Given his name, it’s fair to assume that he is white. We don’t in any case encounter him in the novel, which begins after Sailor goes to prison.

Lynch makes the character a black man, and offers us the “treat” of watching Sailor graphically bash his brains out at great length, on a bannister and then against a marble floor, in public. This is the opening scene in the film, and it happens just after the character leers at Lula, baits Sailor about Marietta’s advances to him in the men’s room, calls Lula a cunt, announces that Marietta has paid him to make this assault, and draws a knife. To top it off, Lynch concludes the scene with a couple of campy gags: Sailor melodramatically lights a cigarette over the corpse and then points, Elvis-style, at Marietta — two gestures that got their expected laughs from the audience both times I saw the movie. For Lynch’s purposes, the implausibility of Bob Ray Lemon’s behavior — he makes his assault in a public place and immediately reveals that he’s been paid by Marietta, simply in order to serve the clunky plot exposition — matters not at all. The only thing that matters is the shock and audacity of the scene, which the audience is invited to enjoy even more because the recipient of the violence is a black man who leers at the movie’s heroine.

Consider the best — by which I mean most effective, as well as best acted — scene in the film, which also happens to be one of the most morally disgusting, and which also has no counterpart in the novel. It takes place between Lula and Bobby Peru (Willem Dafoe), the creepiest and slimiest of all the redneck characters, outfitted with stumpy, rotten teeth and a marine prison tattoo. He crudely puts the make on her alone in her motel room, using endearments like “Your pussy wet?” Then he brutally grabs her and repeats endlessly in a whisper, “Say ‘fuck me,’ say it, say ‘fuck me,'” while running his hand down her body. (It’s just about the only scene in the film where Lynch’s use of rhythm for hypnotic effect pays off.) After she eventually acquiesces and recites the words, he leaps back and hoots, “Someday, maybe I will — but I got to get going.” This produced the desired laughter both times I saw the movie, as did the Lynchian kicker — a close-up of Lula clicking her red-slippered heels together (another Oz reference) as she bursts into tears — but significantly, as far as I could tell the laughs came exclusively from males in the audience. The only purpose of this scene, really, is to humiliate the heroine as thoroughly as possible and prove that she’s every bit as corruptible as most of the other characters — that she’s not only a hot bimbo with a weird imagination, but a slut too.

The biographical sketch of Lynch in the movie’s press materials consists of only four words: “Eagle Scout” and “Missoula, Montana.” I must confess that I share at least part of the sensibility that treasures Lynch’s wild-eyed innocence along with his surreal imagination, his capacity to approximate in some of his sounds and images the haunting purity of dreams. While I find less evidence of this capacity in Wild at Heart than in any of his previous work, there’s still a certain sinister aftertaste that not even the film’s extravagant camp finale can entirely shake away.

“In dreams begin responsibilities,” Yeats once wrote, but I doubt that he was thinking about anything like David Lynch movies, where these two things are made to seem incompatible. Typically, these movies combine something that resembles a free-floating form of religious piety (which most often attaches itself to sex, and characteristically views women as either madonnas or whores) with a sentiment best expressed by Sailor (in the novel as well as the movie): “All I know for sure is there’s already more’n a few bad ideas runnin’ around loose out there.” “Out there” and not “in here” is essential to this sentiment, because a disavowal of any responsibility for those bad ideas is the only thing that allows Lynch and his characters — not to mention his audience — to have them.

Splitting up the world between the holy and the profane, the elect and the scum, also yields some puritanical notions about sex that become the primary colors in Lynch’s paintbox. Sex between Lula and Sailor is great and pure, and sex between Lula and Bobby Peru is exciting (if dangerous), but sex for older folks like Marietta and Mr. Reindeer, the generation of Lynch’s parents, is filthy and literally associated with toilets. (For whatever it’s worth, the fearful notion of the holy hero being sexually assaulted by his girlfriend’s mother cropped up in Eraserhead as well, though without the excremental subtext.) More generally, there’s the view that the world is fundamentally a malevolent place, teeming with predators, disasters, and “bad ideas” but also populated — and justified — by a few holy fools.

Needless to say, these aren’t views based on anything resembling social observation (true or false) or any agenda for changing the state of the world; indeed, they’re predicated on the assumptions that the world is unchangeable and that social observation is useless. And it goes without saying that these are feelings that are not only highly present in our culture, but highly exploitable, for a variety of purposes — political as well as pornographic, mercantile as well as artistic. Whether he knows it or not, Lynch seems bent on covering all of these bases.

But his purpose, so far as one can tell, is simply to have some “fun” — a serious purpose when it comes to making movies, and one that’s generally hard to quarrel with without sounding like a spoilsport. If the fun that he proposes is predicated on the cynical use of cartoon figures rather than characters, and icons rather than people, this is quite compatible with the xenophobia that is already prevalent in our culture in other respects. (And now that we no longer have a cold war to contain this demonology, the paranoid enemies have to shift: the crime syndicate and the working-class scumbags in Wild at Heart are virtual replacements for communist thugs, martians, or creatures with gills in a 50s picture.) And if the fun is also predicated on an absence of conscience that passes itself off as pop religion, with Elvis and Oz’s Good Witch as the only recognizable deities, that goes with the territory as well. To claim that Lynch is ideologically innocent and naive about his neofascist fun seems fair enough. But to claim that he’s ideologically neutral is to succumb to that same innocence and naiveté.