I find it astonishing, really jaw-dropping, that Midge Costin’s mainly enjoyable Making Waves: The Art of Cinematic Sound can seemingly base much of its film history around a ridiculous falsehood — the notion that stereophonic, multi-track cinema was invented in the 70s by the Movie Brats, Walter Murch working with his chums George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, who finally allowed the film industry to raise itself technically and aesthetically to the level already attained by The Beatles.

In other words, let’s forget all about the stereo sound used by Walt Disney in some of the theaters showing Fantasia (1940) and then the multi-track speakers heard in hundreds of other theaters across the country throughout much of the 50s showing scores of films in CinemaScope, Cinerama, and Todd-AO, by pretending that none of this ever happened or existed. In its place we get a new version of events in which Apocalypse Now becomes the pioneering feature that did for Hollywood something like what The Jazz Singer did decades earlier. Or so we’re seemingly asked to assume.

To be fair, this documentary isn’t so much concerned with film history per se as it is with introducing a general audience to what sound work in commercial cinema consists of, and the creative contributions made by a few talented individuals–tasks it performs pretty well. Read more

Though Pere Portabella is a major talent in experimental narrative film, working atypically in 35-millimeter, he’s still relatively unknown because his early features could be shown only clandestinely in Franco’s Spain and none is commercially distributed. The Silence Before Bach is his most pleasurable and accessible film to date, above all for its diverse performances of the title composer’s work. Gracefully leapfrogging between fact and fiction in at least two centuries and several countries, it recalls some playful aspects of his Warsaw Bridge (1989) while juxtaposing past and present as if they were attractions in a theme park. In Spanish, Italian, and German with subtitles. 102 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

George Stevens’s overblown, Oscar-laden adaption of An American Tragedy (1951, 122 min.) is hopelessly inadequate as a reading of Dreiser’s great novel, and as usual Stevens seems too preoccupied with the story’s monumentality to have much curiosity about its characters. But William C. Mellor’s cinematography and the star power of Montgomery Clift and Elizabeth Taylor manage to keep this going. Michael Wilson and Harry Brown wrote the script, and Shelley Winters gives a good performance in a thankless part. (JR) Read more

From the Soho News (September 17, 1980). The owners of this newspaper at the time, if I’m not mistaken, were owners of South African gold mines, and I doubt that this article enhanced my job security — although I remained there as a freelancer for another 14 months.

I haven’t (yet) gone back to Bad Timing to see how wrong I might have been. — J.R.

My Childhood

Written and Directed by Bill Douglas

My Ain Folk

Written and Directed by Bill Douglas

My Way Home

Written and Directed by Bill Douglas

The Gamekeeper

Written and Directed by Ken Loach

Based on the novel by Barry Hines

Bloody Kids

Written by Stephen Piliakoff

Directed by Stephen Frears

Long Shot

Written by Maurice Hatton, Eoin McCann and the cast

Directed by Maurice Hatton

Bad Timing: A Sensual Obsession

Written by Yale Udoff

Directed by Nicolas Roeg

“British Film Now” –- a package of nine programs (at the Paramount Theater on Broadway at 61st) consisting of eleven features selected by Richard Roud, to be shown over six days preceding the 18th New York Film Festival -– is being presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the British Film Institute, with financial assistance from the British Council and the Cultural Department of the British Embassy, the British Film Producers Association, and Amcon Group Inc. Read more

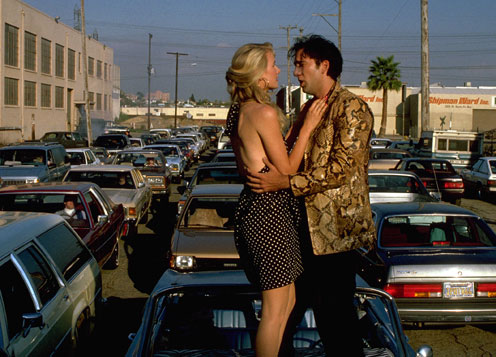

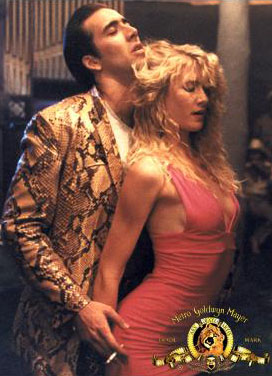

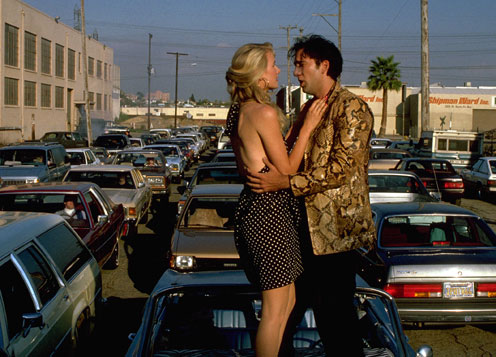

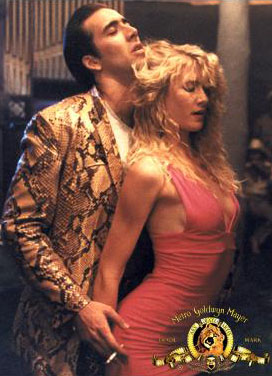

From the August 24, 1990 issue of the Chicago Reader. This is another film (see capsule review of Rita, Sue and Bob Too, posted earlier today) released on Blu-Ray by Twilight Time. For the record, I much prefer most or all of the features David Lynch has made since Wild at Heart, especially Inland Empire. — J.R.

WILD AT HEART

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by David Lynch

With Nicolas Cage, Laura Dern, Diane Ladd, Willem Dafoe, Isabella Rossellini, Harry Dean Stanton, and Crispin Glover.

The progressive coarsening of David Lynch’s talent over the 13 years since Eraserhead, combined with his equally steady rise in popularity, says a lot about the relationship of certain artists with their audiences. A painter-turned-filmmaker, Lynch started out with a highly developed sense of mood, texture, rhythm, and composition; a dark and rather private sense of humor; and a curious combination of awe, fear, fascination, and disgust in relation to sex, violence, industrial decay, and urban entrapment. He also appeared to have practically no storytelling ability at all, and in the case of Eraserhead, this deficiency was actually more of a boon than a handicap. Like certain experimental films, the movie simply took you somewhere and invited you to discover it for yourself. Read more