From the Soho News (September 17, 1980). The owners of this newspaper at the time, if I’m not mistaken, were owners of South African gold mines, and I doubt that this article enhanced my job security — although I remained there as a freelancer for another 14 months.

I haven’t (yet) gone back to Bad Timing to see how wrong I might have been. — J.R.

My Childhood

Written and Directed by Bill Douglas

My Ain Folk

Written and Directed by Bill Douglas

My Way Home

Written and Directed by Bill Douglas

The Gamekeeper

Written and Directed by Ken Loach

Based on the novel by Barry Hines

Bloody Kids

Written by Stephen Piliakoff

Directed by Stephen Frears

Long Shot

Written by Maurice Hatton, Eoin McCann and the cast

Directed by Maurice Hatton

Bad Timing: A Sensual Obsession

Written by Yale Udoff

Directed by Nicolas Roeg

“British Film Now” –- a package of nine programs (at the Paramount Theater on Broadway at 61st) consisting of eleven features selected by Richard Roud, to be shown over six days preceding the 18th New York Film Festival -– is being presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the British Film Institute, with financial assistance from the British Council and the Cultural Department of the British Embassy, the British Film Producers Association, and Amcon Group Inc. -– a Consolidated Gold Fields Group Company.

The latter is on e of the biggest gold mines in South Africa and, rightly or wrongly, I find it a bit difficult to shake entirely the image of South African workers slaving away at subpoverty wages so that culturally deprived New Yorkers can be exposed to British art movies, at the bargain rates of three bucks a ticket. Considering the trade-offs that legislate other aspects of what we do or don’t get to see from abroad, this is scarcely an isolated case of bizarre exchanges made on our mute behalf. But it’s one that nevertheless should be acknowledged, as part of a cultural context.

It would be misleading to imply that this context has played any role whatsoever in the selection of films. But it does seem worth pointing out that, to judge from the seven of the 11 features that I’ve seen (treating Bill Douglas’s trilogy as three films instead of one — as they are in fact, if not in programming), the choice is essentially safe and noncontroversial. There are no avant-garde films included, and no films that reflect the theoretical interests of such English film magazines as Screen, Screen Education, Afterimage or Framework, nor anything quite as eclectic as, say, Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo’s Winstanley.

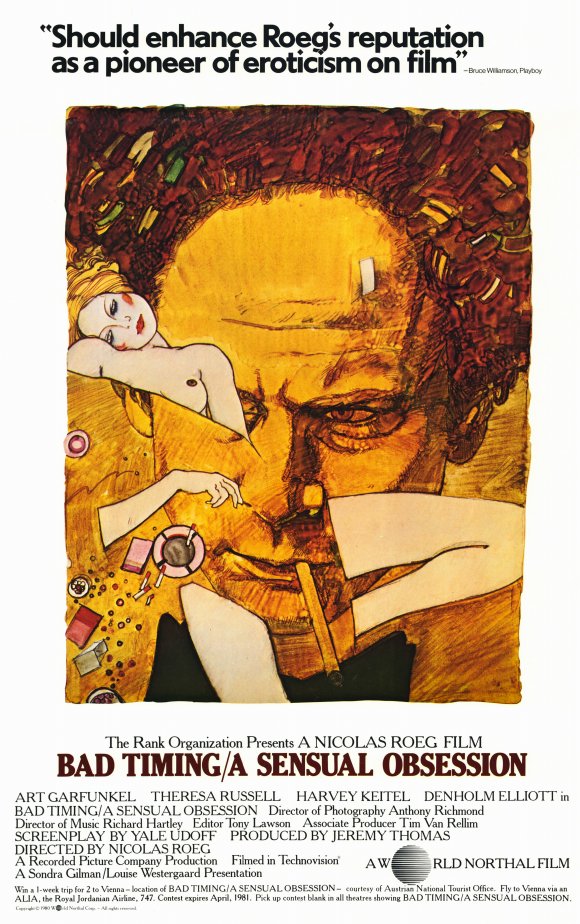

Within these limitations, there are still plenty of movies worth seeing for one reason or another. At the top of such a list, I’d put Bill Douglas’s My Childhood (1972), the first and shortest film in his autobiographical trilogy, running only 48 minutes. At the grim bottom, I’d place the latest Nicolas Roeg film, Bad Timing: A Sensual Obsession — an unfortunate piece of posturing that I’m afraid might turn out to be almost as popular as Jordache T-shirts, perhaps for related reasons.

Taking the last and worst first, let me go on record as being a onetime Roeg buff who still nurtures some fond memories of Fahrenheit 451 and Petulia (which he shot), Performance (which he codirected), and Walkabout (his first film as solo director) — not to mention some fleeting moments in The Man Who Fell to Earth (mainly ones involving David Bowie, TV sets, and Panavision-Bandaid compositions), and some even more fleeting ones in Don’t Look Now. And Bad Timing, to be just, offers an appealing performance by Theresa Russell — even if this happens to be in one of the silliest pieces of culture-vulturism since Woody Allen started pretending to depict intellectuals for the benefit and comfort of middle-brows with inferiority complexes (as in Interiors and Manhattan).

Part of this process –- also displayed in some of the slickest films by Joseph Losey (especially when he was aping Antonioni in the 60s) and in the sodden Brando sections of Apocalypse Now -– is the prominent display of gilt-edged (or guilt-edged) cultural items as reference points. A Godard, Snow, Rainer, or Rappaport can often play this sort of game with some wit –- perhaps because they have nothing in particular to “prove” while an Antonioni at least has a structural point to make when he alludes to Tender is the Night in L’Avventura. But Roeg shovels in heavy-duty stuff about Gustav Klimt, the Viking Portable Blake, Harold Pinter, the Lescher Color Test, Billie Holiday, Freud, and Paul Bowles’ The Sheltering Sky like someone trying to prove he once went to college.

Admittedly, Klimt is probably a fair thematic cross-reference for the male relishing of female suffering (also implied in the Klimtian ads) that seem to lie at the heart of the film — a tradition that Ingmar and Woody, among others, have already done their utmost to authenticate. (At its tackiest, this strain can be felt in the jazzy cuts from the heroine’s sexual seizures to her surgical ones, and back again –- more fun than a barrel of cries and whispers, with lots of gushing blood, too).

Then there’s the embarrassed presence of Art Garfunkel as an American “research psychoanalyist” in Vienna, saddled with a doppelganger detective (Harvey Keitel with an Eastern European accent) to clear up the matter of his beloved’s suicide. This conjures up a replay of the Sherlock Holmes plus Freud formula first broached by The 7 ½ Percent Solution and more recently explored by several recent American avant-garde films– summed up in Keitel’s weighty line, “Vot is detection eef not confession?”, which sounds even better if you twist it around. Indeed, the movie tries so strenuously to be up-to-date that it already seems at least 12 years old (the same age as Je t’aime, je t’aime, which it also occasionally evokes).

As a pure expression of grief-stricken poetry, My Childhood is as memorable in a way as such Continental counterparts as Shoeshine, Germany Year Zero, and The 400 Blows. Conceivably more pared down and less sentimental than any of these, it also winds up being so elliptical in spots that one may have a little trouble getting all the characters and their warped relationships straight -– a problem that recurs just as much in My Ain Folk, the immediate sequel. Set in the dreariest of impoverished Scottish mining villages in 1945, and shot in (you guessed it) grainy black and white, the film opens with the sound of air-raid sirens –- a succinct introduction to evocative, economical uses of sound and silence throughout the trilogy.

Concerned with the filmmaker’s horrifically brutal and loveless youth, My Childhood is a collection of highly subjective reminiscences (“Douglas includes only those moments that people remember forever,” Elizabeth Sussex has noted) without any detailed attempt at analysis. After having tried to plumb my own past subjectively and analytically on paper, I’ll admit I have some trouble with any realist aesthetic that suggests that the past is retrievable (or even “knowable”).

On the other hand the bracing poetry conveyed by some of Douglas’s sounds and images winds up meaning a lot more to me than any ontological assumptions he might have about them. A scene in which the hero’s cousin, after killing a cat out of desperate spite, rushes down to a railway bridge and is sprayed with steam from a passing train, his arms wildly extended like some ecstatic Christ, offers one of the few moments of genuinely lyrical emotional release that I can recall seeing in any movie this year.

It’s mainly in the two sequels (My Ain Folk, My Way Home) that the more prosaic limitations of the realism begin to become apparent. When the latter proceeds to follow the hero into the R.A.F. in Egypt in the 50s, the focus becomes at once too diffuse and too conventionally bildungsroman. But My Childhood — and parts, at least, of its successors — testify to an intense concentration of violent and oddly pastoral memories.

For all their acute differences, Ken Loach, Stephen Frears, and Maurice Hatton are all sufficiently post-Brechtian to situate their realist fantasies on a terrain where some form of social analysis is enacted. The Gamekeeper, Bloody Kids, and Long Shot all deserve some credit for the subtly didactic nature of their fictions, which succeed in teaching the spectator a fair amount about their respective subjects without any heavy strain or sweat.

The low-key strategies of Loach, for instance, include a division of The Gamekeeper into seasonal categories, each one accorded an explanatory chapter heading (e.g., “Spring -– collecting and incubating the pheasant eggs”). A nicely acted TV film that takes its time, but is never half as dull as one feels it easily could be, it quietly etches out a critical portrait of a dutiful Yorkshire gamekeeper. The contradictions in his social position that gradually emerge -– his fanatical concern for his boss’s property and domain, and the relatively uncertain grasp he maintains over his own (family and home included) –- is neither forced nor strident, but lingers afterward like a slightly bitter aftertaste.

At the opposite end of the dynamic scale is Frears’ raucous saga of fugitive punks on the loose, Bloody Kids — another film made for England’s ATV Network.The two main kids in question are 11-year-olds, although one falls briefly under the protection of a creepy older hood (Gary Holton) who suggests a youthful Timothy Carey in spots. In fact, the relative solidarity of all the bloody kids here in contrast to the dumb adult world seems as polarized as the social world of The Wild One.

Shot by Chris Menges in bright, brittle primary colors and set in eerie contemporary locations (disco, shopping mall, a hospital clogged with surveillance equipment)), Bloody Kids exhibits a lot of the panache already shown in Frears’ former Gumshoe. More complexly than any other film treated here, it presents us with a definitive sketch of a futile, closed world of possibilities -– one that makes the despairing, absurdist, quasi-suicidal gestures of its goof-off characters seem almost like the only reasonable game going.

Made on a shoestring, three rubber bands, and a paper clip –- without even enough budget for a partridge in a pear tree -– the likable and lightweight Long Shot is about trying to raise money for a film called Gulf and Western set in Aberdeen, a Scottish oil boom town. The movie never quite makes it to Abdedeen, but it does take in the Edinburgh Film Festival and London, before shooting off to Hollywood for a brief epilogue in color.

Wim Wenders, Susannah York, her agent, and John Boorman are among the characters enjoyably coerced into playing themselves. Stephen Frears turns up as a friendly outsider who finds the manufacture of biscuits no less problematical than cinema. There’s no doubt that the poverty of this movie has more charm than the production values of Bad Timing, even though it’s Hatton, not Roeg, who seems to do the most globetrotting.Prospective independent filmmakers in search of some gentle truths about their profession are advised to see the movie and stop wasting money on plane tickets, even if this might help to clean up the image of a South African gold mine.