From the Chicago Reader (June 24, 2004). — J.R.

Fahrenheit 9/11

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Michael Moore.

It’s bracing to see the documentary coming into its own these days, generating some of the excitement and interest that accompanied foreign (mainly European) pictures back in the 60s, when there were far more independent theaters to show them. But the New Wave and its many tributaries were perceived by critics and audiences largely as a revolution in style; the new explosion of interest in documentaries has more to do with content. Think of the broad range of subjects covered in the past few years by ABC Africa, Bowling for Columbine, Oporto of My Childhood, Joy of Madness, Stevie, The Same River Twice, Capturing the Friedmans, and My Architect: A Son’s Journey. This year alone has brought such diverse explorations as El Movimiento, The Fog of War, Les modeles de “Pickpocket,“ Super Size Me, Ford Transit, Control Room, and Route 181: Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel.

Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11, the most explosive of the lot, has enjoyed the biggest buzz of any film released this year, especially after winning the top prize at the Cannes film festival in May (from a jury that was more American than French). I saw it less than an hour before starting this review, too little time to contemplate whether it deserves to be called a masterpiece, but I already prefer it to Moore’s previous features. It’s far more ambitious, offering a multifaceted and nuanced reading of America in the past four years. It presents and interprets so much information that by the end my head was reeling with the kind of intoxicating overstimulation one rarely gets from popular documentaries. Little of this information is new, but Moore packages what’s already known about George W. Bush and his presidency into a piece of rhetoric so persuasive that the Bush reelection campaign could spend the next five months trying to refute it.

As many other reviewers have noted, it’s far less an ego trip than Moore’s other films and much more purposefully focused. It’s also just as funny and sarcastic, whether it’s turning the invasion of Afghanistan into a TV western starring Bush’s cabinet members or ridiculing Donald Rumsfeld as he notes the “care” and “humanity” that went into the choice of bombing targets in Iraq. (On the whole, the film reveals much more of the Iraqi people than our TV news has.)

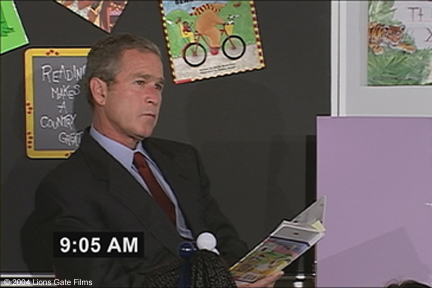

Moore also demonstrates a certain filmic intelligence not apparent in Roger & Me (1989), The Big One (1997), Bowling for Columbine (2002), or his cable series, The Awful Truth (1999-2001). It’s most apparent in his skillful and sensitive depiction of the September 2001 attack on the World Trade Center and its immediate aftermath. First the impact of the airliners is presented as audio accompanying a black screen, then Moore gives us reaction shots of stunned Manhattanites and finally a slow-motion rain of debris. His elliptical treatment of a Christmas Eve army raid on a Baghdad home later in the film is equally effective. (Certain other shots are as ugly and blotchy as anything in The Big One; Moore has grown as an editor, but he still doesn’t care if a piece of found footage looks terrible.)

But whether or not Fahrenheit 9/11 might qualify as a masterpiece matters less now than whether it can help remove Bush from office, and in that respect Moore’s most important achievement is delivering to American moviegoers many facts about George W. Bush and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that our TV news has downplayed or ignored. (Sure, it’s manipulative and slanted — but transparently so, unlike Fox News or CNBC.) In fact, the current popular documentaries have scored at the box office precisely because they help fill in the enormous gaps created by our depleted and corrupted TV culture. In one sound bite Britney Spears blindly endorses the president, as self-annihilating a statement as most of the nonsense dispensed by the politicians.

Moore’s success in hitting most of his designated targets becomes apparent if you look at some of the hysterical attacks lodged against him on the Internet, which also indicate just how primitive the state of American awareness about our media can still be. Two objections I’ve encountered are (1) that documentaries are supposed to be “objective,” apparently in the same way our TV news is, and (2) that Moore couldn’t care less about ordinary people, that he’s only interested in making money, as opposed to all those humanitarian and patriotic chums of Dick Cheney working in Iraq. (At one point in the movie, a grinning executive points out that the war is “good for business, bad for the people.”) Of course, objectivity in a documentary (or a film review) is not only impossible but undesirable. The merit of Fahrenheit 9/11 lies in its ability to enrage you — or, conversely, to clarify some of the rage you already feel — without abandoning the capacity to entertain that has always been Moore’s trump card. As a popular entertainment, it provides the kind of emotional and conceptual counter-myth we sorely need to replace the Bush administration’s crumbling version of reality.

In that sense Fahrenheit 9/11 reminds me of Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940), another rambling, semicomic wartime polemic. (The recent efforts of pressure groups to prevent exhibitors from screening Moore’s film are hardly unprecedented; according to the 1976 Oxford Companion to Film, The Great Dictator was “refused a license” in Chicago when it came out, “perhaps because of the large German population there.”) I’m reminded in particular of Paul Goodman’s contemporary review of the film: “The invective against [Hitler] is to my taste all-powerful: disgust expressed by the basest tricks of low vaudeville, gibberish, belching, dirty words, and radio static. You will not find the like outside of Juvenal. It is so successful that even many of the slapstick errors do not fail to create the impression ‘Good! Hit ‘im again!'” The radio static has a parallel in Moore’s blurry video images.

Fahrenheit 9/11 has been characterized as an anti-Bush polemic, though surely if it were only about Bush we’d all be bored out of our skulls. Moore is no less scathing in his treatment of Congress, circling the Capitol building in an ice cream truck to read the Patriot Act aloud for those representatives who never looked at it. He also documents the Senate’s dismissive treatment of black representatives who came to the Senate chambers to protest the disenfranchisement of their constituents in the 2000 election. In fact, black and working-class people turn out to be the film’s true heroes — a part of its dramaturgy and argument that Moore develops with considerable skill and nuance.

Ironically, the politician who plays the heavy in the Senate footage is none other than Al Gore, eliciting applause and laughter from the Senators as he shuts down one representative after another. Yet Gore’s hour-long speech for MoveOn last May 26 is the one expression of anti-Bush rage that I find more persuasive and eloquent than Fahrenheit 9/11. (Even so, it was dismissed as hysterical and misleadingly sampled the same way on every TV news show I saw.) Moore’s equal-opportunity ridicule is worth stressing because his film, whatever its effect on the election, is too smart to reduce its stance to Democrat versus Republican or liberal versus conservative. (He can even mock his own paranoia, as he does on his Web site, noting that right wingers “want to limit or snuff out any debate or dissension. They also don’t like pets and are mean to small children. Too many of them are named ‘Fred.'”) At a time when our national debate often degenerates into factionalized spats based on party and ideological allegiances, Moore’s respect for simple humanity and common sense is admirable. The film’s most powerful spokesperson turns out to be a midwestern mother whose son, Sergeant Michael F. Pederson, was killed in Iraq on April 2. A conservative white Democrat with a black husband, she prides herself on the American flag she flies in front of her house. She may be a stand-in for Moore — another portly populist icon — but the film manages to present her as more than a useful rhetorical device. As with some of the suffering Iraqi women we also see, we can understand where she’s coming from.